Trump’s foreign policy moves have been polarizing to say the least - but with competing voices within his own cabinet involved, the strongman approach may not be the ultimate outcome of the early administration’s moves.

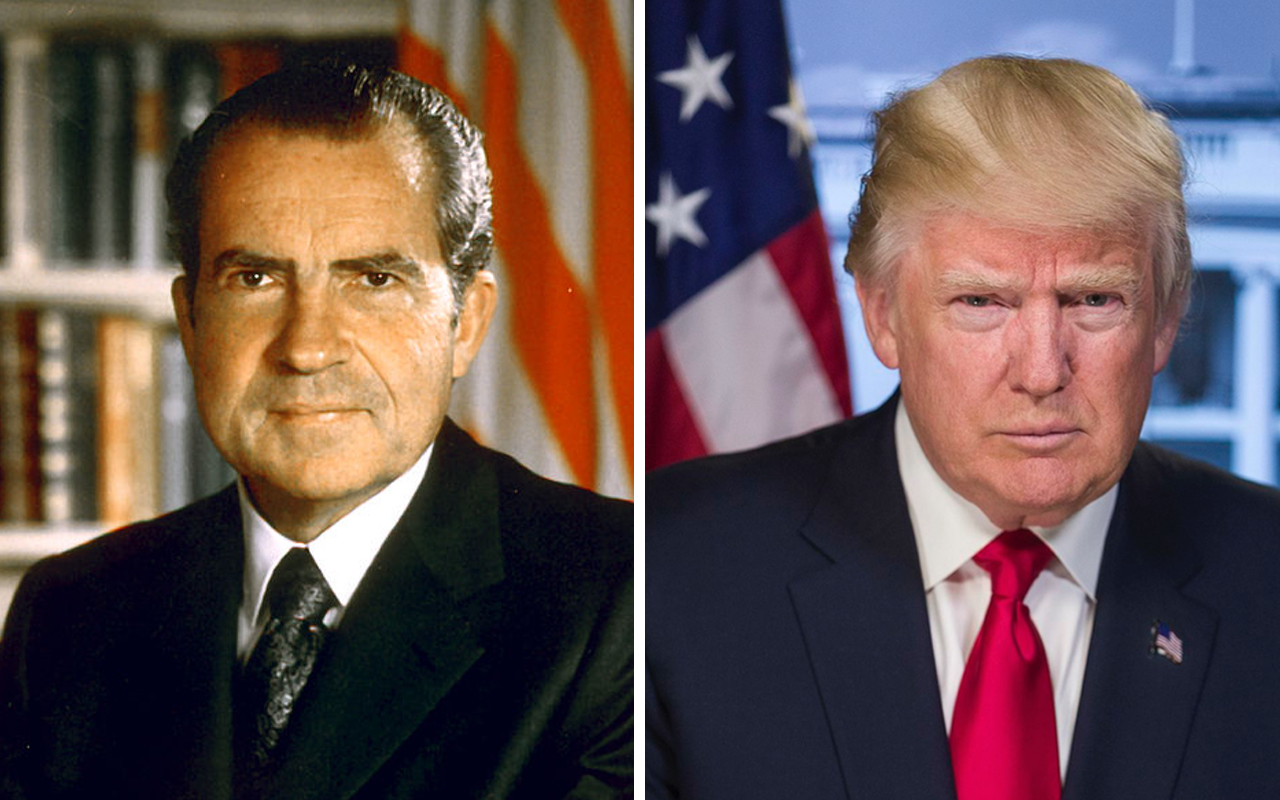

In parsing the often unconventional and consistently bombastic foreign policy of President Donald J Trump’s second term, analysts have opted increasingly to invoke a particular shorthand, “Reverse Nixon” – a direct allusion to then-President Richard Nixon’s manoeuvre, with assistance from National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, for the U.S. to dethaw relations with Communist China.

Nixon’s visit to China in 1972 took place at the height of the Cold War. With reciprocal interest from Chairman Mao Zedong and the masterful diplomat-in-chief, Premier Zhou Enlai, the Nixon-Kissinger duo paved the way to cement the Sino-Soviet split, indirectly precipitating the isolation of the Soviet Union. Indeed, some would attribute to this landmark breakthrough the eventual collapse of the once-great power almost two decades later.

Fifty years later, the touted “reversal” is invoked to describe the proposed strategy of driving a wedge between China and Russia – two states whose synergy and complementarity have only strengthened under a decade’s worth of attempts by the U.S. and its Western allies to cripple the Russian economy in the aftermath of its 2014 annexation of Crimea.

From Beijing’s perspective, deepening ties with its northern neighbour has been a no-brainer in light of the escalating pressures from the West, which have concertedly framed China as the primary target motivating Washington’s “Pivot to Asia” strategy. From Obama through Trump I to Biden, China and Russia have found in one another convenient partners – with significant efforts dedicated towards shoring up energy, financial, economic, and technological ties.

A “Reverse Nixon” today would play out through American retreat from all direct points of conflict with Russia – including, first and foremost, Ukraine, but also domains of counter-intelligence and cyber-espionage – and re-allocation of strategic resources towards the cause of containing China’s strategic rise. In the eyes of its most ardent defenders, China is the primary “threat” to the U.S. – not Russia.

In parsing whether the Trump cabinet is aiming to adopt this strategy vis-à-vis Russia and China, we must disaggregate this issue into two questions – firstly, is there any interest or intention to do so? Secondly, irrespective of the intentions at hand, could a “Reverse Nixon” emerge as a result of actions undertaken by the incumbent American administration?

The picture shows a painting of Xi Jinping, Trump and Putin in an art gallery in Yalta, Crimea. It is called "Yalta 2.0" and imitates the Yalta Conference of the Big Three of the United States, Britain and the Soviet Union at the end of World War II.

Is there the intention to accomplish a ‘Reverse Nixon’?

In an interview with Breitbart News, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has declared that the US cannot let Russia become China’s “permanent junior partner” – speaking with the strident confidence of a man accustomed to pontificating over the decisions and relations of other sovereign states on the planet. He warned of the risk of the further bolstering of ties between Beijing and Moscow, whilst openly remarking on the case – and challenges – for the US to dilute the bilateral relationship without sowing divisions.

There is little doubt Rubio’s words likely reflect the thinking behind a more conventional, China-sceptical wing within Trump’s foreign policy circles. In a piece co-authored with Matthew Kroenig last year, now-National Security Advisor Michael Waltz remarked that China had been the greatest beneficiary from the policies of the Joe Biden administration –fostering more resilient bonds with Russia in the aftermath of the latter’s invasion in 2022. Despite the conventionally Russo-sceptical stance of both Rubio and Waltz alike, both view the Sino-Russian-American triangle through relatively instrumentalist lenses: for the sake of shoring up American supremacy, their priority would be to double down on intensified technological, military, strategic, and economic warfare against China – and not Russia.

Yet as evidenced by the visible discomfort and alleged consternation expressed by Rubio on the sidelines of the historic Trump-Vance-Zelenskyy spat, the Floridan politician’s foreign policy outlook does not always reflect that of his immediate superior. A more accurate reading of Trump’s personal vision – to the extent that is possible – is likely to point to a 19th “Concert of Europe”-esque constellation of powers. In a prescient piece penned in 2016, historian Niall Ferguson drew upon Kissinger’s advice to adopt a “Metternich”-style approach to global affairs for Trump: one in which the U.S., Russia, and China could each have their “sphere of influence,” and respect the somewhat arbitrarily drawn yet resolutely enforced boundaries across such spheres.

In his first term, Trump took little heed of this vision – and opted for a botched, shabbily, and incoherently executed strategy of ratcheting up trade and economic conflict with China, prior to launching an all-out rhetorical assault on China in the wake of the pandemic. As he returns for a second term, it is improbable that the Chinese and Russian “spheres” can be disentangled in the way that powers in the “Concert” were. Fundamentally, this worldview would leave small and medium states around these great powers bereft of agency and options – after all, who is to determine where the boundaries of each sphere of influence must lie? In this game of shifting goalposts, it is the small states who inevitably lose out.

None of these, of course, amounts to reasons for which Trump would not thereby embrace a 21st century “Metternich” strategy – in my view, a more accurate depiction of his intentions than the “Reverse Nixon” move. From floating the idea of American control over Greenland to asserting its interests in Panama, from dismissing Canada to humiliating Mexico, Trump has made it emphatically clear that he craves control over the North and South Americas. On issues ranging from Taiwan to Ukraine, however, he has been overtly cavalier – almost flippant.

Perhaps amongst the most indicative of the remarks he spewed at Ukrainian President Zelenskyy, were Trump’s admonishing the battered politician for “gambling with World War Three.” Trump is deeply sceptical and wary of the potential for further military escalation in Eastern Europe, under his watch.

With his close advisors Elon Musk and Tulsi Gabbard’s emphatically affirming the narrative that Russia was provoked into war by alleged NATO expansionism, and with his public boasting of his personal relationships with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Trump has made it clear that he believes America must broker “deals” with fellow strong powers – namely China and Russia – to secure its domestic interests. In short, Trump’s fixation upon “Making America Great Again” is a primary inward-looking, parochial pitch – one that coheres well with the vast swathes of disillusioned working-class and lower-middle-class voters fed up with what they lambast as the “forever wars” in which the U.S. has perennially been enmeshed.

Could ‘Reverse Nixon’ be the outcome, even if unintended?

Picture a timeline where the “21st century Metternich” and “Reverse Nixon” camps continue to tussle within the Trump administration, and where Washington vacillates between the two for the next twelve months. A germane and separate question, then, concerns whether Trump’s antics may inadvertently result in a “Reverse Nixon” scenario – even despite his personal apathy and disinterest towards this outcome.

My prediction is that whilst Moscow would indeed seize upon the opportunity to pursue de-thawing of economic, financial, and commercial relations with Washington, it would be hesitant to overtly distance itself from Beijing. This is especially the case in view of the intense scrutiny and attention Chinese diplomats will dedicate to monitoring the every move of the Russian administration – thanks to the raucous talk of a “Reverse Nixon.”

Firstly, the Sino-Russian food and energy partnership has become deeply integrated over the past few years, no less thanks to the severance of many of the energy ties between Europe and Russia (see, for instance, the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines, on which reparation efforts have begun). China imported a record amount of Russian crude oil in 2024, and has become the primary supplier of renewable technologies to Russian firms and enterprises – epitomising a synergy between old and new energy sources. Russia eyes Chinese food and agricultural technologies with keen interest, whilst China has positioned the Sino-Russian Land Grain Corridor as integral to its food security.

Secondly, Russia has become substantively dependent upon China in its financial and banking sectors. The Chinese yuan amounted to 54% of trade in Russia’s stock exchange. Moscow views BRICS+ and the RMB internationalisation as integral prerequisites for the dismantling of a US-dominated financial hegemony – one in which sanctions and penalties can be arbitrarily and devastatingly imposed to advance Western interests. It is not in the Kremlin’s interests for Beijing to be weakened considerably, or lose in its competition with Washington.

Finally, whilst the Kremlin may leverage its dethawing relations with the U.S. to nudge Beijing into granting more concessionary treatments and terms over jointly developed economic zones – e.g. in the Far East – such tactical moves are unlikely to come at the expense of the overarching stability of the Sino-Russian partnership. At the end of the day, Trump and his cabal could well be gone in four years’ time – which would precipitate another drastic, 180-degree U-turn in the U.S.’ Russia policy. In contrast, the case for robust relations between China and Russia is likely here to stay. In short, a “Reverse Nixon” is neither reflective of Trump’s likely intentions, nor a particularly probable trajectory of events.