Podcast by James Chau on Sep 05, 2025

Podcast by James Chau on Sep 05, 2025

Podcast by James Chau on Sep 05, 2025

In this interview with China-US Focus host James Chau, Ananth Krishnan, Director of the Hindu Group and former head of The Hindu’s China bureau, explores the strategic choices India is making to shape its role on the global stage, including its delicate balancing act between China and the United States. He addresses common misperceptions, particularly following Prime Minister Modi’s recent visit to China for the SCO Summit, and explains how India navigates major powers while prioritizing its own interests.

Podcast by James Chau on Jan 19, 2024

The China-United States Exchange Foundation cares about the issues impacting humanity, including climate change and climate justice. In this podcast, President James Chau speaks with Special Advisor for Global Goals Laura de Belgique. They discuss the link to health, the recent COP28 in Dubai, and collective action in 2024. Recorded in Bozeman, Montana.

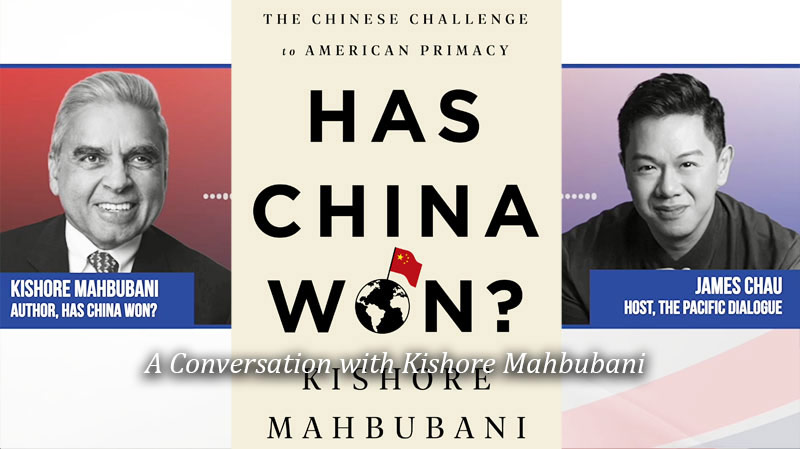

Podcast by James Chau on Nov 11, 2020

We return this week with a special conversation with Kishore Mahbubani, the diplomat, academic, and author whose books help us understand and navigate the unfamiliar shifts overwhelming the world. ‘Has China Won?’ is his new release, about a country and a people he knows well, and the challenge it presents to American primacy. This, he describes as the foremost contest of the 21st century, where the US he writes has “abandoned” multilateralism, while China embraces it. Mr Mahbubani speaks with James Chau.

Podcast by James Chau on Apr 16, 2019

James Chau, host of At Large, the in-house podcast of China-US Focus, interviewed Peking University Professor Wang Jisi in Hong Kong, during which the prominent Chinese scholar of American studies discussed the recent media reports of FBI barring some Chinese scholars from visiting the U.S. over spying fears, the rise of racial profiling in the U.S. and racial discrimination across the world. Professor Wang also discussed the growing U.S.-China rivalry, the concerns that China is moving backward, and his optimism that China is ultimately moving in the right direction. The following is a transcript of the interview.

JAMES CHAU: It's a great pleasure for me to be sitting with Professor Wang Jisi, who is a professor in the School of International Studies and President of the Institute of International Strategic Studies at Peking University. He was, of course, the Dean of the School of International Studies prior to that, and he's held a number of visiting fellow or visiting professorships at Oxford, at UC Berkeley, at the University of Michigan, at Claremont McKenna. And we're delighted that you can be with us here today because you're going to lend your insight both as a thinker, but also as a mover, as the China-United States relationship continues to take on new forms and new shapes.

Professor Wang, let's start off with talking about what everybody is talking about. Just to time-stamp this conversation: it is April 16th, 2019. Two days ago, there was a news that came out in the New York Times about the FBI barring some Chinese scholars from visiting United States over spying fears. This is part and parcel of a growing perception, that somehow Chinese academics, and the millions of Chinese students who have gone to the United States over the years since Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy Carter opened up that exchange, are a threat to security in America. Is that true or not?

PROFESSOR WANG JISI: Of course not. I think the exchanges between Chinese American scholars and students is a great contribution to the bilateral relationship and we, in China, scholars and students, have benefited a great deal from the exchanges and we’ve also contributed towards the understanding between United States and China. So I think when I heard about the story, I didn't hear simply from the press. I got to know that quite a few months ago. So I feel very sad about all of this and I think it is quite unfortunate that the FBI is harassing some Chinese scholars. Personally, I have not been affected. But when I travelled to United States, people ask, "do you have a visa problem? Are you going to be interviewed by the FBI? Or are you going to use your visa going to be cancelled? This is a tough question because some of my fellow students and some of my colleagues have been in this situation several times, so I think that could be addressed properly between the two governments. I think that we in China should work harder for the mutual understanding between the two peoples.

JC: I want to go more into the emotions of it because we're not just talking about a relationship, we're talking about millions of people and you amongst them within that mix. As I mentioned before, you've held roles within some great American institutions and also you spent nine months at the Woodrow Wilson School as part of your four years there as a Global Scholar. Obviously, it's not just about work, it's about personal friendships, intimate friendships as well. How does it make you feel when people talk about your community of academia, and say that you're not contributing? In fact, you are a threat to them?

PW: This episode has happened, when the U.S.-China relationship has been deteriorating for some time, so it's connected to the larger political climate in the bilateral relationship. But it is not simply that. I think the United States is seeing China as a threat or as a rival and we scholars have actually been contributing to the bilateral relationship. And we are not threats to the United States. If you see China as a threat, it will become a threat because it hardens not only the American attitude toward China, but it could backfire in the Chinese scholarly community.

So, many people ask ourselves and ask Americans what is going to happen if our friendship, our good feelings about the United States are being hurt by these incidents? I think that is important, but also necessary: we are not a threat. When you see China as a threat, the you know, the people in China are actually friendly to the United States, and China as a nation-state - I don't think it is a strategic threat to the United States. If we were having problems toward each other in our bilateral relations, like trade or security problems, we can sit down and talk about it.

Some of us are suspected by the Americans as serving the interests of our nation's intelligence community. They suspect that we are working for the intelligence community. But this is very normal that scholars like us have connections with our governments. I have also connections with American government. I talk to American government officials very often, of course, and I talk to Chinese officials very often. We brief them about bilateral relations, we make suggestions as to how we improve relations. We don't give them this proposal that we will do harm to the United States, and of course we don't want to do anything harmful to China.

JC: This is very interesting, because on the one hand, you could see it as a movement towards a "nation-state" as you described it, but the Committee of 100, which many people know is a collection of some of the most prestigious and influential Chinese-Americans in the United States - all them United States citizens, put out a statement the other day, they said that they're compelled to stand up and speak against what they call the racial profiling that's becoming increasingly common in the United States, where Chinese-Americans

are being targeted as "potential traitors, spies and agents of foreign influence". They call that statement "racial profiling". So are we looking at a movement against China as a country, but in addition to that, racism against an ethnic group?

PW: I think that is a phenomenon quite common in the world today. In a world of turbulence, in a world of division along ethnic, religious and racial lines, there are people who suspect that other races are harmful and not as intelligent as themselves. And that is not simply happening in United States. It happens in Europe, in some Asian societies, everywhere in the world, so we should guard against racism and ethnic discrimination. I think the case of the Committee of 100 is just a reflection. So, it is not simply a problem for Chinese communities in the United States, but I think it's also a problem with some other Americans of different ethnic backgrounds and different origins. I think we should not only

resist the call of racism in the United States, but we should also do that in the world at large.

JC: It is somewhat ironic that this statement, the phenomena you described comes at an exact point where the Chinese-American community, and Chinese everywhere, are marking the 150 years since the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad, which helped connect people in America, which helped them move. But of course, was very sad chapter for many of the people and families involved because of the element of human suffering: It wasn't just about going to America to get a job. It was about improving lives, but it was also a very painful sacrifice for many people.

PW: Yes, I think you refer to this kind of history, and we in China will remember very clearly those episodes of the relationship. When many Chinese came to United States, especially from Guangdong, Fujian and other coastal provinces, they worked very hard. They earned very little.

And at the same time, we should remember that they were Americans going to China. Many of them contributed to China's modernization. So we should remember those people, rather than to say that they did anything bad for the United States or for China.

JC: We could talk more about the Exclusion Act, which was a piece of legislation that banned the entry of an entire ethnic group - the Chinese - in the later part of the 19th century. But let's move on. By moving on, I would like to take you back to an essay you wrote in 2005. So, 14 years ago, and I was reading it because I thought on the Foreign Affairs website that it brought up so many points that could easily be reapplied 14 years later in 2019. You wrote that "the United States is currently the only country with the capacity and the ambition to exercise global primacy, and it will remain so for a long time to come". Do you stand by that today - does the U.S. occupy that position as the "lonely superpower"?

PW: I think the relative power of the United States is declining, in the sense that China's catching up some other countries like India are also rising up very rapidly. But I still insist that China and the United States are two rising powers. China is rising faster than the United States. but there is still a long way for China's to catch up with the United States - economically, militarily and in terms of soft power. I emphasize the importance of soft power because I think the soft power of the United States has been shrinking in the last few years, and China's soft power is rising up as compared to the past. But in terms of what we call comprehensive national power, China is lacking still very far behind the United States. For instance, in scientific research, in technological know-how, in management skills, in higher education and high school education, we are lagging behind.

JC: I interviewed Professor Joseph Nye at Harvard University two weeks ago, and we talked very much about collaborative competition, about smart competition. It appears to be a new line of thinking in terms of how to create an innovative solution to get the China-United States relationship moving again. But in fact, you wrote about this a long time ago: you said "a cooperative partnership with Washington is a primary importance to Beijing with economic prosperity and social stability are now top concerns". We should remember that economic prosperity and social stability continue to be top concerns in a country where about 50 million people are still living in extreme poverty. Those goals haven't really shifted in that time. As you said, the relative gains in terms of China as an improving, progressive nation has obviously gone forward. But cooperative partnership - what did you predict 14 years ago? You brought it up a long time ago.

PW: China and the United States cooperated, engaged with each other, and also worked together to solve problems like climate change. The competitiveness at the time was not as intensified as it is today, because China is catching up economically. China is getting rich, much richer than 14 years ago, total GDP of Chinese is about two thirds of the United States today. So that is a very significant change. But I think the fundamentals remain the same. When we talk about educational and scientific levels of analyses - in that regard, China is catching up. But we should remain very modest and sober-minded, as to what we should do at home.

So I think the competitiveness in the United States-China relationship has been more evident, more apparent, than 14 years ago and this is something very new. But I agree with Joe Nye when he emphasized that China and the United States are still working together and we should avoid over emphasizing China's rise of power and America’s relative decline - and I joined him in many discussions and we are of about the same opinion. On the one hand, the Chinese are proud of themselves for good reasons. On the other hand, we should also realize that as compared to our past, we are catching up but when we compare with some advanced economies, like Japan and the United States. We should still learn from their experiences, we should caution against too much pride on our side.

JC: We've been doing a number of interviews since the start of the year to honor the first 40 years of the China-U.S. relationship, and as part of that, of course, the 40 years of reform and opening-up. When you think back for decades ago, I think of the archival footage of Deng Xiaoping going to the United States, over at the Space Center, on the White House South Lawn. There was a very warm relationship, personal relationship between him and Jimmy Carter. They created these wonderful frameworks for the two countries: it's not just about two government is about millions of people bringing the best of the world together, and merging their talents. What's gone wrong?

PW: It is two-fold. That is not something “going wrong", but something different from the Deng Xiaoping years and 40 years ago. The first thing is China's rising up, China is more powerful, more capable. The second point is also very important: that is China's domestic changes, and America's domestic changes. The United States is facing mounting pressure from problems like economic inequality, the rise of populism, and political polarization. You talk about many things that are different today from the Carter years.

On the Chinese side, we have also experienced many events. Of course, we are catching up economically, but we have daunting, mounting pressures at home. For example, environmental degradation, ageing is another problem, poverty relief is still a daunting task. So, there are many problems at home. We are making progress economically. but we should also think of our own problems like economic inequality. Populism is also rising in China, nationalism is rising in China. There are multiple problems that are different from 40 years ago.

One thing happening is that the Americans have lost their patience. When they thought about China 40 years ago, or 30 years ago, they thought that China would become more like the United States - achieving democratic, political pluralism, more diverse views, and a rising middle class that will change the political system of China. Their hopes are dashed and shattered. Some of them are complaining, complaining about themselves. Some are complaining about China going back to the old days - a reference to the Mao Zedong years, not the Deng Xiaoping years. Some people complain that some of the policies are driving China back to the old days. I'm not so pessimistic. I think there will be twists in history, ups and downs in the bilateral relationship, but we should remain optimistic that China is changing - and China is changing ultimately in the right direction.

JC: It is great speaking, hearing and reading what you have to say. Professor Wang Jisi, thank you very much.

Podcast by James Chau on Mar 26, 2019

China-US Focus Editor-at-Large James Chau on March 24, 2019 interviewed Joseph Nye, University Distinguished Service Professor of Harvard Kennedy School, in Cambridge, MA. Professor Nye is also a contributor to China-US Focus. The following is the edited transcript of the interview.

James Chau: Professor Nye, thank you very much for having me here today in Cambridge, Massachusetts. If you look outside this glorious window and terrace that you have to your left, what do you make of the world as it stands?

Professor Nye: It's a more difficult world than it was, let’s say, 10 years ago, but I am not a pessimist about the long-term future. I think that things are somewhat chaotic, but when people tell me this is the worst it's ever been, I say, you’ve forgotten the 1930s, you’ve forgotten the 1960s. This is not the worst it’s ever been and I expect over time, things may improve.

JC: If we look to the 1970s, that was the beginning of the movements [towards] a U.S.-China relationship in the modern sense?

PN: It was. The 1970s, after the meeting between Nixon and Mao, was the start of a new relationship, but it was also very much forwarded by Deng Xiaoping’s policies, and the [diplomatic] recognition of course in 1979, and there was a period of quite good relations and improving relations that went through the ’90s. It really doesn't turn sour again until basically in a recent period. I think since the Trump administration, things in [the] US-China relationship have gotten considerably worse. But it’s important not to blame it just on Trump. There was already a bipartisan disillusion[ment] with Chinese policy before the 2016 election.

JC: That said, it was supposed to be a celebration of some sort at 40 years. How do you see the relationship evolving given all the new settings and complexities that you just described?

PN: Well, right now we’re of course involved in a trade war and that makes things difficult, and we don't know how that will be resolved. There are really two types of issues. One, is the bilateral trade balance, which President Trump often focuses on. But that's not the real problem. The real problem is more related to coercive intellectual property transfer. Basically, there was a disillusion[ment] in Washington, both among Republicans and Democrats, about the way China had, if you want, ‘tilted’ the international trading relationship by subsidies to state owned enterprises, by coercive intellectual property transfer, by theft of intellectual property. This left a very bad taste in both political parties. But it also weakened support for China among the American business community, which had been a part of the political system and had been most supportive of China in the Congress. And so even before Trump was elected there was a difficulty. I’ve sometimes said that it was like a small fire was burning before the 2016 election, and then Trump was elected and he became a man who threw gasoline on the fire. But the fire was already there before Trump.

JC: When I spoke to President Carter [a] couple of weeks ago, he talked about the U.S.-Japanese relationship and how there was also not only some resentment from the recent historical past, but also how the Americans had felt that Japan had tilted the trade relationship more to its own favor. He then used his own example of setting up what was then a three-man panel— three men from Japan, three men from the United States, and he offered this as a potential model for today. Men and women, of course, anonymous, so they can work effectively, and report to their presidents who can then work together. Does that work in the ways and with the opportunities and resources that we have now between these two leaders?

PN: It's possible that you might have some benefits from a wise-persons group, but President Trump is [a] very idiosyncratic president or individual. He's unlike previous presidents and sometimes he doesn't even listen to the advice of his own closest advisers. He’s been known to tweet something, just the opposite of what his secretary of state has said. So it's not clear in the case with President Trump that the recommendations of a group of respected seniors would be able to change the views of the President. I’m not against such an idea, but I wouldn’t hold it having a very high likelihood of success because of the unique nature of this particular president.

JC: You mentioned social media, and you yourself are a selective tweeter. In recent posts, you asked an important question. You ask, can we learn to collaborate and compete at the same time? What does that mean in the US-China context? What does smart competition mean to you?

PN: If you look at the U.S.-China relationship, rather than seeing it as a new cold war, we should see it as what I've called a ‘cooperative rivalry’. There are going to be elements of rivalry— take for example, issues like the South China Sea, but there are going to be areas of cooperation, areas like climate change. We have to learn to realize that the relationship is going to be complex, but if we lose sight of the cooperative part of the relationship, we’re all going to be the worse off for it. Climate change is a very major issue, even though President Trump doesn’t pay attention to it or doesn’t accept it. But I think you're going to find that by the next American president, whether that's in 2020 or 2024, public opinion is moving in a direction of taking climate change seriously. We’ll also see damages done by climate change, and I think when people realize that we have to do something, they realize that you can’t do it unless the US and China cooperate, as the two largest powers in production of greenhouse gases. So I think that the important point is to educate the public to the fact that yes, we'll have areas of rivalry and competition, but we'll also have areas where neither of us can accomplish what we want without cooperation.

JC: When we look at the other areas where there are potential overlaps, ironically, perhaps not trade in the current setting. You’ve talked about climate change, but what about innovation, global governance, or security? What's the cleanest slate they could work off together?

PN: I think for example, governance in the area of cyber-relations are going to be important. It's interesting that Xi Jinping and Obama had begun to make progress in this with their meeting in 2015. Now it seems to [have] fallen by the wayside, but at some stage we’re going to have to get rules of the road for cyber. So there’s an area of global governance where I think we’re going to have to not necessarily agree completely, because we have different views, but find rules of the road that we can cooperate together. But I think there are other areas as well. International financial stability requires a degree of cooperation between our countries. Issues that may be dormant now, but could become very important in the future, are global pandemics and cooperation in global health. These are not things which either of us can solve by ourselves..

JC: Ironically, I often feel that ‘smart competition’, if it's done respectfully on both sides, could help extend the U.S. unipolar moment. Am I being too much of an optimist?

PN: Well, I think the unipolar moment is over, in the sense that that period in the ’90s and early 2000s, after the Soviet Union had collapsed, is not going to return. The Americans are still likely to remain the strongest power in the world— I don't think that China or anybody else is about to surpass the Americans in power, but they are going to be a lot closer than they were in the past. And in addition to that, there’s a greater diffusion of power among not only more states, but also non-state actors. Sometimes people call this ‘multipolarity’. It’s really much more complex than that. The U.S. could remain the dominant power in, let’s say, military power. There’s no other country able to project military power globally like the Americans can. But in economic power, the world, it is multipolar and in areas of transnational relations there are many more actors. It doesn’t make sense to call it unipolar or multipolar. It's a poly-centrism, if you want. So I think we’re not likely to see return of unipolarity. I think that was a brief moment.

JC: Would it be such a bad thing for there to be a greater sense of a shared space, even if countries were coming closer to one another?

PN: I think the United States has got to adjust its foreign policy attitudes to realize that we can't think just of power ‘over’ other countries, we have to think of power 'with' other countries. Many of the things that we want to accomplish can only be done with others, not just by trying to have power over others. So I think President Trump’s attitudes of ‘America First’ are the wrong way for American attitudes to develop. Every country puts its own interests first. Leaders are elected to represent their country's interests. But there’s a big difference between ‘America First’ or ‘China First’, meaning short-term self-interest, and meaning an enlightened long-term self-interest which respects the interest of others. And I think a post-Trump president is going to have to move our attitudes in that direction.

JC: Let us also talk about the larger Asia[-Pacific] in its engagement with America. You regularly visit the region. I think you were recently in Beijing and also in Tokyo and you noted a ‘Chinese concern’ that a cold war, that Jimmy Carter also warned of at the turn of this year, is in the offing. But you say that unlike the U.S.-Soviet example, the U.S.-China dynamic is very different at a very different time as well. Is that going to be enough to protect the world and protect humanity?

PN: I think that’s correct, and in that sense, the reason I don't think there's going to be another cold war is if you look back on the U.S.-Soviet Cold War there was almost no trade and there was almost no contact among peoples. And whereas if you look at the US and China today, not only is there massive trade, which is hardly a source of contention, but there are massive exchanges of people. I read something on the number of Chinese students in the United States around 375,000 or something. Chinese tourists in the United States are in the millions, and American tourists in China similarly. These are good things. That social entanglement of the countries makes it more difficult to isolate and demonize the other country, and set some limits on the amount of conflict that grows out of the rivalry.

JC: I’ve been trying to listen hard to what American thinkers are saying. Some of them have expressed it as an approach that sees America reserving the right to respond to Chinese abuses while working with [China] when it chooses to. But rather than ask about the American approach, what would you say the Chinese approach should be?

PN: One thing is that Chinese leaders have to be aware of what I call, 'Two Audience Problem’. if you say that China will be first in artificial intelligence in 2030, as Xi Jinping has said, that may play very well in Chinese politics, but that plays terribly in Washington. It means China is going to defeat the U.S. by 2030. So, what sounds good in Beijing sounds terrible in Washington. Find a way to express that, which doesn't make it a direct challenge, that focuses more on the cooperative-sum aspects rather than the zero-sum aspects. And that goes for the way in which China sets its program of developing technologies, which will be important for China, and nobody can prevent or should prevent China from developing them. But if you use coercive intellectual property transfer, if you use intellectual property theft, if you give special subsidies to state-owned enterprises, if you don’t have reciprocity so that Alibaba can list in Washington, but Google can’t play in China, these give rise to resentment. And so if China wants to find a modus vivendi with the U.S., it has to be aware of how its policies and its statements are playing in America.

JC: So, on the one hand you're saying it's a question of communication, of branding, of expression, but also at the same time that it has to be backed up by the meat?

PN: Exactly.

JC: I mentioned to a friend today that I was coming to meet with you and she said to me, “It’s funny how collaboration and competition are antidotes to me”. The alternative though of course, I think, is a possible 'red scare' that we have seen not so long ago. What do you think will be the prevailing opinion? Do you think people will wake up to a certain approach or will it be the approach as they are familiar with at current?

PN: Well, I suspect that we’re going to go through several years of this suspicion and lack of trust in the relationship. It’s unfortunate, but it's going to take changes in policies in both countries—In China, the types of changes I just mentioned and in the U.S., I don't think much is going to change until the next president. We don't know if that'll be 2020, or 2024. But I think in the long run, the U.S. and China do not present existential threats to each other. Neither of us is trying to destroy the other. And that means that the rivalry is something we can manage. It doesn’t lead to the kinds of fears that we had in the 1930s about Hitler and Hitler’s Nazism, or the fears we had in the 1950s about Stalin and Stalin’s communism. So, whatever one thinks about the differences in our two social systems, and they are different, it's quite possible for us to have rules of the road that let us live and let live, and to also cooperate. But right now the domestic attitudes in both countries are not very healthy for this.

JC: So as the global leader that you are, if you were to project and anticipate, what would you tell us is the major trend or an important trend to come, and how should we prepare ourselves for it in advance?

PN: I do think that there are going to be common transnational challenges, and they are ones that no one country can solve by itself. So, if we don't learn how to cooperate, we’re not going to be able to achieve our own objectives. Climate change is a classic example of this, in the sense that I think it's going to get a lot worse and that we're going to have to cooperate to be able to deal with it at all. But many of the other issues I mentioned, whether it be transnational terrorism or whether it be cyber-relations, whether it be global pandemics, these are issues where nobody is going to be able to accomplish it by themselves, so we’re going to have to develop these networks of cooperation if we’re going to govern and manage these types of processes. And that means that we're condemned to cooperate, because if we don’t, we are really just condemned.

Podcast by James Chau on Jan 26, 2019

January 17, 2019, Atlanta

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Wu Xinbo is Dean of the Institute of International Studies and Director of the Center for American Studies at Fudan University

JAMES CHAU: We have just come from a lunch where the speaker warned that the bilateral relationship is deteriorating, with severe consequences for the future. Drawing on your own insights, what does that future look like?

WU XINBO: Two of the biggest regions in the world are now entering a state of major transformation, which may take a long time to complete. We are currently at the beginning of this process. We see the change in this relationship not only in the atmosphere, but also in the substance. In terms of the mutual perceptions towards each other, I think people in two countries view the other side more negatively compared to before. As a matter of substance, the two countries now have serious disputes on the economic dimension, security dimension, and political dimension of this relationship. This is quite rare to a certain extent, because in the past, we would also run into problems in the relationship – sometimes on the political side, sometimes on the security side. But this time, the situation is more comprehensive. The overall relationship seems to have run into a structural dilemma. The question for the future is really whether we can still maintain cooperative relationships with competition as part of this picture, or else this relationship will move to be more confrontational as a result of competition. So, thinking about the future really tests our imagination because this is the first time since the normalization that we are facing this kind of situation.

JC: As I speak with you, I noticed that you're wearing a lapel pin with the two flags of China and the United States together. For the past 40 years, this has been one of the great stories of contemporary history: how these two countries have established a global future that's more secure and healthier than before. Earlier you mentioned feeling that this is just the beginning, and that there are more transformations to come in this relationship. Should we just adjust ourselves to a new sense of normalcy and abandon the one that has been the pillar for the past four decades?

WX: Well, I think there are currently different trends driving this relationship. So, we should not allow this relationship to be just carried forward by various trends. The people in our two countries should make sure that this relationship will not only be stable for the next 40 years, but more importantly, cooperate with one another, so that it will serve the interests of the two countries as well as the interests of the entire world. Now, in the US, the administration does not have much interest in globalization and global governance. The current US administration tends to view relations with other countries, including China, in a narrowly defined and bilateral context. And this is why it has chosen to pursue a more unilateral-based approach to relations with other countries, including with China. If we do not have a broad perspective of the US-China relationship, it is very difficult to introduce elements of cooperation in multilateral settings at a global level. And as a result of that, you will pay more attention to the competitive side of this relationship without thinking about the broader picture. So, to get back to your question, yes, we should work hard to make sure that we always put this relationship in a broader perspective. And always against a backdrop which reflects global needs. If we can do that, then we can keep competition in perspective. When people focus more on competition, we should remind them and ourselves to never forget that there is a great potential for cooperation between our two sides.

JC: You describe this current administration as being one that is not interested in globalization, but at the same time, the current leadership in China has been rewriting the multilateral story. You have Bo’ao (Bo’ao Forum for Asia), BRICS, Community of Nations, Belt and Road, the BRICS Bank, and more and more. Is China simply going to spot an opportunity in the absence of the United States and seek other partners? And where could those partners come from potentially?

WX: I think globalization has come to a stage in which emerging economies are going to play a larger role simply because they are becoming more important in the global economy and they have more resources to contribute to globalization. So, we should understand China's growing role in globalization and global governance in that context. Having said that, I still believe it is very important for China to promote globalization in two ways. One is to continue to work with the U.S. and other developed countries because to some extent the U.S. is still indispensable to this process, given its role in international affairs and especially given the role of the U.S. economy in the world economy. So healthy globalization cannot proceed without an active role from the United States. On the other hand, China will also continue to work with emerging economies – India, Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia – because they are becoming more and more important. If this is going to be a process based on two pillars, we have to make sure that the two pillars will match each other as they move forward. So, even though in recent years China has paid more and more attention to cooperation with emerging economies, I think China-U.S. cooperation remains essential and crucial to the healthy development of globalization.

JC: On that point, I want to go beyond the bilateral relationship to the bigger meaning of this relationship in how it impacts humanity. If we look back at the decision in 1979 to normalize diplomatic relations, it was to bring more than a billion people together on opposite sides of the planet to help unify the dream for a better tomorrow. With that in mind, do you think China has the capability as an emerging nation to make a true impact in this dream for a better tomorrow? We still live in a world dominated by the Bretton Woods system. We still live in a post-World War Two structure where the world, as the United States sees it, is very much in its own image?

WX: Let me put it this way. Over the last four decades, China has been a major beneficiary of the international system, especially on the economic front. For China, it is very important that we are working with other stakeholders to continue to maintain and preserve the current international order. That's for sure. On the other hand, of course we understand there are many deficiencies with the current international system which need to be repaired, improved, reformed, and even supplemented. China should also work with emerging economies and the developing world to push for the necessary improvement and reform of the current international system, and whenever necessary and possible, we should also help create new institutions that will supplement rather than replace the current international institutions, especially in international financial and economic dimensions. I don't think this is going to be a process in which China can make the decision and shoulder all the burdens alone. It requires China to work more skillfully not only with other emerging economies, but also the developed world, particularly the United States. In this regard, a new challenge is going to be how China can work with the Trump Administration, which has become more suspicious of the current international system and has also become more reluctant to shoulder its responsibility for global governance. It is quite a big challenge for China.

JC: There is an identity crisis emerging here. Young people around the world are struggling to find their place in a rapidly changing global structure. What would you say to young Americans and young Chinese about their place in the world today, and how can they prepare themselves for the future?

WX: We must realize that the world is changing very rapidly. We need to keep an open mind to these changes, and not try to evade or resist the tide of change. We should recognize that this is an interdependent world. It is a challenge for young Americans to see competition from China and India. What they can do is better prepare themselves to meet this challenge. As for young Chinese, they must learn how to work with others, to be open-minded, and to learn from others. On the future the two countries: how can China and the U.S. co-operate in the 21st century – not only to bring prosperity to the world, but also peace and security? As China is becoming more prosperous, more capable, and more self-confident, it is quite a challenge for Americans to learn how to live with a China which may be different from the one they are familiar with. And as for young Chinese, as they feel more self-confident, they must learn how to work with others, to be open-minded, and to learn from others, including young people in the United States.

JC: Two very interesting sides of a coin that you just described. You’re not just a leading authority on the bilateral relationship, but of course you're also a leading educator as Executive Dean at the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai. As such, you shape young minds. What do those young minds say to you? What do they think about the U.S.?

WX: Frankly, students at Fudan University find it harder to believe that the U.S. is in a positive state of affairs. Looking at the current government shutdown that has been record-breaking, one can’t help but ask, “What happened with the political system? Why can’t the two parties compromise for the national interest? Why doesn’t the U.S. political system work as well as it did in the past?” Students also find some of the Trump administration's foreign policies, especially on the economic front, against the traditional way the U.S. conducted relations with other countries and with other multilateral institutions. The U.S. has become more nationalistic, more protective, and sometimes even more irrational. People are trying to decide whether this is just a transitory situation or if it will be the new norm for the United States. When they come to me with these questions, frankly speaking, I cannot answer with full confidence.

JC: You seem to have a good sense of understanding for your students. You have a great eye to history as well, and not just in the last couple of decades, but far before that. You wrote a book, Major Powers in China, which looked at the make-up of China at the turn of the 20th century. Could you have predicted what’s happening in the United States now? Could you have predicted what seems to be a new turning point in this relationship?

WX: History always take turns, sometimes in very unpredictable ways. Over the last century, we have seen ups and downs in China’s national history: Japan’s invasion of China, the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Cultural Revolution, and in 1979 the start of Reform and Opening Up. For the United States, I would say to some extent, this is its first major test since the end of World War Two. Before the advent of Trump, I think that the US was moving along a trajectory laid out by leaders post-World War Two. Trump may be the first US president since World War Two who has decided to turn inward, if not for an isolationist agenda, certainly for a more protectionist agenda. This will have huge ramifications, not only for US relations with other countries, but also for the U.S.’s international standing. I think this kind of change to some extent came as a surprise because, though we understood the U.S. would be entering a more turbulent era after the 2008 financial and economic crisis, but the change in policy has happened so quickly and dramatically since Trump has come into office. Frankly speaking, that change went beyond my expectations. So today I believe I need to spend more time thinking about the U.S., not on the East and West coasts, but rather the US in the heartland, and what really happened in the Midwest that reshaped Americans’ mindset about their relationship with the outside world. So that remains a challenge. Whether or not the U.S. will come back to its normal situation remains an open question. But I sincerely hope that the U.S., in the not too distant future, will become more outward looking, more metropolitan, more internationalist, and more cooperative in its relations with other countries, including with China.

JC: The end of the Second World War and the period that immediately followed that marked a dismantling of the then British Empire, the breakdown of colonization. And there you really saw the United States beginning to accelerate very quickly forwards, which benefited not just Americans, but a lot of people outside the United States as well. Coming up to 2019, will there be a power sharing agreement? China is still far behind in certain respects to fully replace the United States, but will the United States have the capacity to give a little space to China if it continues to grow?

WX: I think the U.S. is divided over this question of whether or not it should be more accommodating to a rising China. If you look at the case of the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) that was created by China in 2015 when Obama was president, the U.S. responded to this initiative with a very discouraging attitude. Basically, the U.S. tried to block China from establishing this new multilateral financial institution. I think behind that is a mentality that the US does not want to share power with China in the area of international finance. As we all know, Obama failed to block China’s initiative. The other question is whether people in this country learned lessons from that. Some may have, some may not have. So today, when I'm reading the debate in the U.S. about how to deal with a rising China, I think the primary base behind the U.S. attitude is maintaining U.S. primacy, vis-a-vis a rising China. One solution is that you should try to slow down and, if possible, disrupt China's rise. So, the current trade war between China and the U.S. can be partly explained by this kind of thought process. That is something worrisome, because frankly speaking, if the US aims to slow down or even interrupt or disrupt China’s rise, the U.S. will pay a very high cost, given the high degree of economic interdependence between our two economies, and that will lead to a lose-lose situation. I think Americans need to think very hard on how to make the best use of the rise of China, to help promote the U.S. economic rules, rather than trying to contain a rising China, where the U.S. will pay a high cost.

JC: Wu Xinbo, it's a great pleasure listening to your insights and thoughts at this very challenging time for everyone.

WX: Thank you.

Podcast by James Chau on Jan 25, 2019

January 17, 2019, Atlanta

FULL TRANSCRIPT

David Lampton is Oksenberg-Rohlen Fellow at Stanford University and Director of SAIS-China at Johns Hopkins University.

JAMES CHAU: David Lampton, it’s a great pleasure speaking with you. Earlier, I asked you why you are sometimes called David and why sometimes Mike, because you're known to everybody orally as Mike Lampton. You told me this great story about how when your mother would be angry with you, she would call you David, and when she was happy with you, she called you Mike. So, may I call you Mike?

DAVID LAMPTON: You may, I’d be happy to have you do that.

JC: Is it a ‘Mike’ relationship right now between China and the United States? Or is it really ‘David’ as so many people have been warning, including eminent figures such as Jimmy Carter, who have that historical long view of the relationship?

DL: I think that's the popular characterization or relationship, but when my mother was really upset with me, she called me David Michael Lampton. So, I think we're somewhere between ‘David’ and ‘David Michael Lampton’ in terms of the evolution of domestic politics and attitudes towards the relationship in both countries. One of the many reasons for this is because we're both going through demographic transitions. I'm of the baby boom generation post-World War Two and the biggest conflicts of the Cold War where we're with China, directly in Korea, and then later in Vietnam. So, when my generation came through and we've had the last 40 years of peace with China my generation remembers that, but now we're passing the torch and both our societies to a generation that has no experience with the downsides of bad U.S.-China relations. They've lived in a bubble of a growing economic and cultural ties, and I don't think they have a full appreciation of what poor or counterproductive U.S.-China relations could mean.

JC: Let’s say you're speaking to someone now in your class who is 28 years old, born well after normalization in 1979. What would be the one or two messages that you would give them about the alternative you know too well?

DL: First of all, I started out in my career in the late 1960s and the very way I learned about China was essentially to read documents that were Xinhua documents. I went to Hong Kong, which was my first trip to Asia, for the purpose of interviewing people who left China. I planned my career on the presumption I would never go to China and I would never talk to Chinese people that were in China.

JC: Why?

DL: Because Nixon hadn't gone, there was the Cultural Revolution. There were a few people that literally swam down the Pearl River into Hong Kong harbor, and those were the people you could talk to. So, my whole research strategy was basically to read a very limited media that came out of China and talk to people who were unhappy enough to leave China. Now, most people stayed in China and that meant that they either were happier about that, but they certainly had a different experience. But I had to try to learn about China under the presumption I would never go to China. My career has turned out to be rather different, and my greatest source in the end has always been the opportunity to talk to Chinese people, both common people and leaders at various levels. So, I would tell students now that you have an opportunity by virtue of normalization and everything that followed to go to China to understand it, the opportunities you have, were not even conceivable when I started my career. I think that's the first thing I would say. And secondly, war is a very costly thing. I was in the U.S. army reserves as a medic and I saw the human casualties of a mismanaged relationship. Those are not abstract. When you see people that are damaged by war, this is very tangible. Our generation, of course, we've had a lot of experience in the Middle East and Central Asia, but China is of an entirely different scale. If we have trouble managing wars in small states, imagine the problems we would have with a big state like China. I think it's just extremely important for the welfare of our young people to find ways to manage this relationship.

JC: Your first contact with Chinese people was via Hong Kong, which of course at the time was British-ruled. It was very different and that's where people escaped to at the time. Where does the story with the mainland itself begin and how different was that experience?

DL: For my first trip to China, we were supposed to go in early September 1976, I was part of a National Academy of Sciences group. It was on steroid chemistry, steroid chemistry being the ingredient for birth control pills, and China was very interested in that. One of the first delegations they invited was a steroid chemistry group, and I had written a book on the politics of medicine in China, so the National Academy of Sciences asked me to go along with this group. Between the invitation and our departure Mao Zedong passed away, and so China put a 30-day halt on foreign groups entering China. We were the first American group to go into China after Mao died and we landed in Beijing on October 10th, 1976. At that moment the Chinese people really didn't know who their leader was. Hua Guofeng had not yet even appeared. We weren't quite sure who was in charge of China at that moment. Finally, they were sufficiently worried about us, that we went down to Guilin, and they didn't tell us why we went there other than to look at the scenery. We stayed there a few days and then on, I think it was the 21st of October, they took us to Shanghai and Shanghai was celebrating the fall of the Gang of Four in Beijing. And there was what was called the 'little Gang of Four' in Shanghai itself. My first exposure to China was to see it after Mao had gone, when the Chinese people weren't quite yet certain what the new situation was and where the Cultural Revolution was very rapidly becoming denounced and rejected as the path forward. So, the Chinese people were coming out of a long period of internal dissent and conflict, and they were very interested in a group from the United States at that moment.

JC: Even Jimmy Carter said that in 1978 he still didn't know who was in charge in China in the way that you expressed. Of course, you predated that experience by a number of months. My reference in terms of the Chinese people coming out, as you put it, would be in a more contemporary period, the Beijing Olympics and also some of the tragedies like the Sichuan earthquake that happened that same year. What for you is ‘China’? What for you captures who the Chinese?

DL: I'll always remember an old man in one of the Beijing hutong on that first trip. At that time China was a city of alleyways. I got up early one morning and at that time people weren't quite sure whether they should be talking to foreigners. I had spent all this time trying to study Chinese so I could talk to Chinese, but people on the streets were a little reluctant at that time. I got up early one morning and he was out brushing his teeth on the corner because the water pipes were outside, not predominantly in many of these buildings, and I came around the corner and surprised him and he was a little nervous talking to a foreigner that spoke Chinese. I noticed next to him was a pile of dirt, just a big pile of dirt. So, I asked him, why, what's this dirt? I thought I would ask something not sensitive. As it turns out, Beijing was having a tunnel digging. They were worried about an attack from the Soviet Union and still some worries about the United States, and there was an underground tunnel building. It turns out this dirt was from these tunnels. Suddenly, I was asking him the most sensitive question instead of the least sensitive. So he looked at me, and he looked at the dirt, and then he looked at me and then he looked at the dirt, and he says, “What dirt?”, as to deny the existence of it so he didn't have to answer the question. This always struck me as a very sophisticated reply to an unwitting foreigner who didn't quite understand the situation. I've always remembered that old man.

JC: One of the books that you wrote is The Three Faces of Chinese Power: Might, Money, and Minds. Why ‘might, money, and mind?’

DL: There's an intellectual reason and that is that people who study power would generally say that there are three kinds of power. There's what you would call coercive power, the capacity to force you, perhaps even physically or psychologically to comply. Then there’s what you might call remunerative power, the capacity to bribe people to affect their material incentives, and then there's the third form of power, normative ideological power, which is the power to persuade you to you do something because you think it's right. So might is the coercive, money is the remunerative, and mind is the realm of intellectual persuasion. I've always felt that the realm of intellectual persuasion is the most efficient form of power. It's the least resource intensive. Coercive power is extremely expensive as I indicated about war, and of course economic transactions, as part of human nature. Deng Xiaoping essentially restored the economic incentives, Mao wasn't big on economic incentives or material incentives – he was big on spiritual, ideological. I guess the central point of that book really was that Americans tend to place their emphasis on course of power, but I think China in its modern development, while it hasn't ignored coercive military power, puts the emphasis on economic power and the support that intellectual power can give it. So, my basic point is, the United States should not exaggerate the military coercive component, but should focus on a positive, healthy competition in the economic and intellectual realms. And I think I ended the book essentially saying something like, if the United States exaggerates China’s coercive power, we will be playing the wrong game in the wrong place with the wrong country.

JC: There seems to be elements of that right now: the China ‘threat’, the China ‘rise’. Where is this going to head next? Beyond the economy, these two countries that have such influence on the way all of us interact with one another, be it technology or be it cultural. To decode them will be to understand and anticipate where we as a humanity are likely to head towards next. What's coming up next in terms of a major trend and how can we best prepare ourselves for that?

DL: I agree with the anxieties that lay behind your question and I agree with the observation that we're headed in an unhealthy direction. I think we're at the early stages of what I would call an action-reaction cycle. Essentially the security apparatus, whether it's in China or the United States, France or Britain, they're paid to think about what could go wrong. They're not paid to think about all the things that could go right. They are charged with preparing for things that can go wrong and therefore they're always looking for what we would call the worst case. What if the other country, whether it's China or, before that the Soviet Union what if they acquire certain capabilities that disadvantage us? And because acquiring new capabilities often takes 10 or 20 years to develop a new system, whether it's China and an aircraft carrier or hypersonic missiles, you have to look 10 and 20 years out and say, "what could go wrong?" The answer is a lot of things could go wrong, and then you'll begin to plan for those and allocate resources and budget. Technology, of course, is always providing new opportunities for future problems. Just look at cyber. Twenty years ago, nobody was talking about cyberwar. Now everybody is talking about it. What you get is an action-reaction cycle: I see what you are doing, and I begin to develop new means to deal with that. You see what I'm doing, and you develop new means to deal with that, and pretty soon you almost have an autonomous process in which each side is reacting, not to what is, but reacting to what could be.

JC: Is that the basis with what's going on with the trade war?

DL: Well, certainly I would say we're in the early stages of an arms race. But then you begin to ask, what is the basis for technological development and its economic wherewithal, and I think the United States is worried about the degree of economic competition. China, by virtue of having so many people, has a lot of data. If you're going to build a new artificial intelligence capability, the more data you have, the more advantage you have in research. So, I think we're beginning to understand some of the advantages China has in economic development. We look at the development of whole new industries like a high-speed rail. China had no high-speed rail industry in 2000, and now it's a world leader in 2019. In less than two decades, China has developed something that was something the French, Germans and the Japanese only had before, so I think economic power is a basis for military power. We see this growth dynamic, we see China's innovation in some of these technological areas, and we wonder what this means to the previous dominance that we had in the world.

JC: So how do we now harness this? You have the second biggest economy that's not close, but getting closer in terms of…

DL: The World Bank say China passed us in 2013 by purchasing power parity. Now, China doesn't use that measure for those purposes. But if you look at the calculations of the World Bank, that's old news. China already passed the US in 2013. Now, there's a debate whether the World Bank measure is accurate and, or a good reflection of relative power. I think the World Bank measure probably exaggerates China's power a bit, but it's only if you don't believe China's already passed us. It's only a question of when it happens.

JC: Okay, it's getting close. In some ways it may have already passed and surpassed the United States. With two economies so close together, how do you provide a solution to a relationship that is then constructive? In the past, that relationship may be more paternalistic. The United States was a sole power and China just climbed out of the Cultural Revolution that you just described. They were still thinking about how, and what, to eat the next day. Now they're thinking about which smart phone they're going to upgrade to next. So, where do you find a happy situation and is that even possible?

DL: Of course, it's possible, particularly when you consider the costs of not doing so. Is this going to be easy to do? No. Is it possible we won't do it? Yes, it's possible we will fail to do it. But remember, this is going to be very costly because then we'll begin to throw barriers on trade, our economic engines will be less efficient than they would otherwise be. We will reduce exchanges and technology transfer, each trying to slow down the other’s capabilities. So, there's going to be a huge economic cost over what we could be if we were cooperating. Also, of course, it could become absolutely negative if you end up in conflict and war. But your question is, so how do we avoid this? That' the question. I think we have to try, and I think there are some avenues. First of all, we have to, in this case, and I don't mean to sound too ‘U.S.-centric,’ but we have to make room for China. China will play a bigger role in the multilateral world. Its role has already gone up in the IMF and the World Bank, And China's built new institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. We have to remember that in the case of the Asian Infrastructure Bank, we actually opposed its establishment. I think that was a blunder. We should have welcomed China participating in the solution of a big problem like the infrastructure in Asia. I think we, speaking as the United States, need to make room for China and not grudgingly, but in a positive spirit. I think that’s a problem we have to deal with. Secondly, we now have moved if you think of Nixon and Carter, Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. They moved towards each other and our two countries move towards each other too. You know, promote economic development but it was an elite-to-elite. It was just four guys, practically, that would get together, and they get a new relationship. But since then we've developed what I would call a society-to-society relationship. Yes, there’s the Washington executive, Communist Party links, but there are state governments, and there are firms or civil society. We are now knit together at many levels and much of what we are calling the problems of US-China relations are really elite-to-elite and government agency-to-government agency. They’re reflected in our societies. But the lower you go in each of these societies, towards civil organizations away from state governments, they have mostly the interest in cooperating. It's the national governments dealing with each other that fight the fights. But the lower you go in each of the societies, the more incentives there are for positive cooperation. I think as our two central governments, so to speak, have more and more difficulties, it’s more incumbent that our local governments, our firms, our civic organizations, they cooperate. Now at some point your central governments can become so antagonistic, they stop this societal cooperation. And, so, I would say if we see a process that is not just our government, the central government is having problems, but the central government then in each of our societies inhibiting cooperative activity at the lower level, then we’re certainly in trouble. I was very heartened when at this meeting you essentially had a former state governor say we got to cooperate at the local level.

JC: Bob Holden of Missouri?

DL: Yes, I think that’s just a reflection. I would say we’ve got to make room for each other in the international system. And we have to get as much cooperation at subnational levels as possible to get through this period until we get national leaderships that can deal better with each other.

JC: You all one of the foremost minds and understanding China and the United States and unpicking the nuances that oversee growth between them, and some of them are very beautiful as well, but I wonder whether we should return to the beginnings of what Deng and Carter did, in bringing students to each country. In doing so, investing in new beginnings, young people, keeping it local, keeping it basic, but at the same time sowing the seeds so that later on, there could be something better to look forward to. Or as the Chinese say, “A better tomorrow than the one today.”

DL: Right, well, if you think about it, even before Carter and Deng Xiaoping or Nixon and Mao and Zhou and Kissinger and all these people we've had, we had experience to build on when they were thinking about the relationship. And I go back to before 1949 there was a huge wave in the 1930s and '40s and even earlier of Chinese students that came to the United States, and for the Americans, it was often missionary educators going to China. But when we reestablished, in the 1970s and '80s, the educational relationship, it was all of these people who had participated before 1949 the provided the interface. If we keep these relations going, even if our national levels have difficulties, we're keeping alive, the pathways of interaction, so it's not all wasted. Even if it's a suboptimal, I would say also you said something very important just in passing. And you said before normalization, we began to move on the students. And that's true. In 1978, before there was no normalization in May, and normalization came on January 1st the following year in 1979. But seven months before that we agreed to exchange students and so forth. That was the first thing Deng Xiaoping did. And in fact, you know, when Deng Xiaoping, he came back more than once actually. And he came back to power in about 1973 and he placed a great emphasis on science and technology. And then of course after Mao died and the transition with Hua Guofeng, he wanted to restore these relations. So, I think it's extremely important that our national – and I give President Carter a lot of credit – he had a priority that was very different than when we dealt with the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union Exchange Principle was, if you send one engineer, from Moscow to the United States, we have to send one U.S. engineer in the same field to the Soviet Union. And it was one for one. Everything was negotiated. President Carter said, send all you want as long as the US government isn't paying for it. It was a totally different principle of exchange, and I think that was one of the wisest and most important strategic decisions that was made at that time. Not to treat China like the Soviet Union.

JC: David Lampton thank you very much.

DL: Thank you.

Podcast by James Chau on Jan 24, 2019

January 17, 2019, Atlanta

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Stephen Orlins is President of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations

JAMES CHAU: You captivated the audience this morning at the Carter Center with your Chinese, and you made me sit up because you very self-deprecatingly described yourself as xiao tudou [小土豆] which of course in English means…

STEPHEN ORLINS: Small potato.

JC: You started life as a so-called “small potato” – though people who describe themselves as such never really are – in the legal department at the U.S. State Department. Tell me about life then and what brought you into contact with China?

SO: It started with my family. My mother was an immigrant to the United States. My paternal grandparents were immigrants to the United States. I grew up in a family where we were taught that, but for the American government and the American people, we wouldn’t exist, we would have perished in Europe. They were European immigrants and Jewish immigrants, and they would have died under the Nazis, or in a Russian pogrom. My parents said that my brother, sister and I owed a debt of service to the American people, and I grew up thinking that I would go to West Point. But the war in Vietnam intervened and I decided that wasn’t the route I wanted to take – I was very anti-war – and instead, I ended up going to Harvard College. Then, on April 30th, 1970, President Nixon announced the invasion of Cambodia, the extension of the American war in Vietnam to Cambodia. Harvard erupted in protest so terrible that the school ended up canceling classes. So, on the last day I was at Harvard, I went to a respected professor and said I wanted to understand why good people – the American government – do bad things like the war in Vietnam, and that I wanted to study Vietnamese. He said, “Steve, if you really want to understand Asia and what's going on, you should study Chinese”. He turned to go away, but then turned back, looked at me, and said, “By the way, if you want to study Chinese, I'll get you a fellowship. Come to my office tomorrow”. This entire conversation lasted less than 60 seconds. I went to his office the next day, filled out a form for a National Defense Foreign Language grant, which I was then given about three weeks later to start the study of Chinese. This less than 60-second conversation began a life-long relationship with China. When I graduated college, I decided to perfect my Chinese by going to Taiwan, where I only spoke Chinese for about 15 months. Then I went to Harvard Law School. When I graduated law school, I joined the U.S. State Department, who discovered after about a year that they had this Chinese speaking lawyer in the legal advisor’s office. I was then put on the team that was going to help establish diplomatic relations with China, which President Carter early-on decided we were going to do. I was put on a team where, interestingly, and why I call myself a xiao tudou, there were a lot of chiefs and very few Indians. So as one of the few Indians, I got to do things which for a 27, 28-year old, were truly extraordinary.

JC: Why do you think your professor gave you the language of Chinese as a vista to understanding an entire continent?

SO: Because the ancient history of Asia was substantially written in Chinese, and so he was giving me a platform to understand Asia, which turned out to be true. He also, by the way, added, “Maybe Chinese might be useful after this war is over” – which was incredibly prophetic!

JC: This was the early 1970’s?

SO: It was 1970. April 30th was the invasion of Cambodia, a date I remember with incredible clarity because of the expansion of the war. And then May 1st was the conversation I had with the Harvard professor, Professor Woodside.

JC: So almost exactly nine years after that conversation, almost an entire decade after your professor transformed your life, Deng Xiaoping went to the United States. When he met with Jimmy Carter in late January 1979, they talked about war, including Cambodia and Vietnam, and also China, Japan, and World War Two. They talked about it so that they would ensure that, in normalizing the Chinese relationship, they would not be responsible for any wars between them. Is that correct?

SO: We forget over time that the original basis for the U.S.-China relationship was an anti-Soviet alliance. The existential threat to both China and the United States was the Soviet Union, and the reason Nixon opened in 1972 and then Carter established diplomatic relations on January 1st, 1979, was to cement the anti-Soviet alliance, which would in their view prevent war.

JC: You’ve talked about the capacity of both governments to set things back on track. The relationship is at a very tricky stage, and surely we can't say it’s just about the current administration. What’s been the undercurrent that has brought these two countries from celebration, to the point where Jimmy Carter says a “modern Cold War” is not inconceivable?

SO: Numerous factors: from changes in the U.S. which lead us to look for a cause for the problems here, to Chinese policies that have strengthened those in the United States who want to characterize the relationship as strategic rivals. It’s a combination of what both governments have done. What’s most troubling in this era is that it’s much deeper than governments. In the United States, academics, think-tanks, and businesses that formerly were supporters of constructive U.S.-China relations are not today. When Chinese students are denied visas, everyone- think tanks, academic institutions, the business community- should protest, because ultimately that decision is terrible for the United States. It’s not just bad for U.S.-China relations, it’s bad for America as the bright shining city on the hill of education. People are protesting, but it’s not in the strength and numbers you expect, because many Chinese policies have made those who formally supported constructive relations unhappy with China.

JC: When you go out and speak to these communities, whether it be business, academic, or political, what do they say?

SO: The business community, which was really the ballast for the U.S.-China relationship, is tired of hearing promises which are not implemented from China. You heard today talk about China's entry into the WTO and how 17 years later commitments are not fulfilled. You heard Craig Allen [President of the U.S.-China Business Council] talk about the government procurement agreement that they would adhere to as soon as possible. Seventeen years is not as soon as possible. It’s getting late. We hear many commitments which ultimately are not implemented. As an eternal optimist, somebody who's seen the changes that I've seen in 40 years, I still believe that a lot of the promises that are made will ultimately be implemented. But there's great frustration in the business community. That's reflected in them not taking as strong a stand as they would have on issues relating to the U.S.-China relationship. The crackdowns on education in China, denying visas to academics from the United States who have written negatively about China, the Chinese government at times trying to influence academic discussions in the United States, has all caused the U.S. academic community, which used to be so strong in its support, to become divided. There still are those who support constructive relations, but there are many who don't speak out. There are many who believe we should have reciprocal policies, where if the Chinese don't allow something, then the U.S. shouldn't allow something. If the U.S. government wants to set up “America corners” in different Chinese universities around China, they're not able to do that. But China has over 100 Confucius Institutes in the United States. So academics say, “Let’s have it be reciprocal, so if China doesn't allow America to do it, then America should prevent China from doing it”. American journalists believe that they are not treated well in China. If I had a dollar for every time an American journalist is invited to have tea with public security, I would have a lot more money than I do, because it's done far too often. The interference in foreign journalists’ work in China is substantial. So that’s led the U.S. government now to require CCTV and Xinhua to register as foreign agents. The risk is that these are then going to become reciprocal restrictions, which is extremely damaging. These U.S. communities, which formerly supported constructive engagement, aren't now. What I said about academics applies to think-tanks. They get tired of having conferences canceled. They get tired of having things they write in English translated into Chinese and not translated accurately. So, they are no longer as strong a supporter as they were. These policies are not good. They are not in China’s own interests. But what's lacking in the U.S. is putting those policies in context. Is China seeking to replace the United States as the world's leading power? The answer is, it’s really not. The Chinese government is interested in maintaining stability in China and maintaining their power, which does not mean replacing America as the number one power in the world. Chinese history, culture, and current problems dictate what they're going to do for the coming 50 years. But the problem is that the constituencies on both sides who were supporters before are not supporters today.

JC: One of the hallmarks of the 40 years, bearing in mind everything that you just said, has been trust, far-sightedness, and the bravery and courage required to make historic decisions as these two men did in December 1978 and leading into January 1st, 1979. Are there the right people in positions of influence right now? And I'm not saying presidents, but communities who are able to do that. Is there the same incentive, if they feel discouraged as you said?

SO: I always believe in the United States government. And I have believed for many years that we don't have sufficient China expertise at senior levels. You can go through the Chinese government and find people who have studied in the United States. They actually know the United States pretty well. Some of them talk to me in English, some of them talk to me in Chinese, but there is this experience. Except for Elaine Chao today, who in senior levels of the U.S. government really knows China? Elaine is Chinese, born in Taiwan, she speaks fluent Chinese, but her responsibility is not China. I felt that in the Obama administration too. [China’s Ambassador to the U.S.] Cui Tiankai can communicate to the American people in English and understands America extremely well. He becomes a force for constructive engagement. You have to go pretty far back to find the equivalent American in China who can speak to the Chinese people in Chinese and convey what is going on.

JC: You said that you were noticed and hand-selected because of your linguistic abilities?

SO: Well, there were no other Chinese-speaking lawyers in the United States government.

JC: Do you think there are many more today?

SO: No, I think not.

JC: Some people would look and say that it is similar to how Chinese students have come to the United States in droves as the U.S. has opened up its educational gateway and allowed them to truly flourish, not only in their careers but also in their lives, but can the same been said of the reverse?

SO: It’s much smaller. Whereas we have 350,000 Chinese students here in the United States, we have 20,000 American students in China.

JC: And why is that? Is that due to lack of interest or a lack of openness?