An estimate of the impact of the tariff war between China and the U.S. on the Chinese GDP in 2025 is presented. The dependence of the Chinese economy on its exports and, in particular, on its exports to the U.S. has been declining significantly over time. At the current tariff rates, a total cessation of bilateral trade is a real possibility. Under the assumption, the reduction in the rate of growth of Chinese GDP may be estimated to be 1.2%, other things being equal. Even though the announced target rate of Chinese growth is around 5%, the weighted average of the target rates of growth of the provincial-level units is 5.26%, indicating room for further increase. In addition, China is expected to launch additional domestic economic stimulus measures in response to the new tariffs, which should result in an additional growth of 0.5%. For 2025 as a whole, a rate of growth of around 4.5% (5.26 – 1.2 + 0.5) may be predicted.

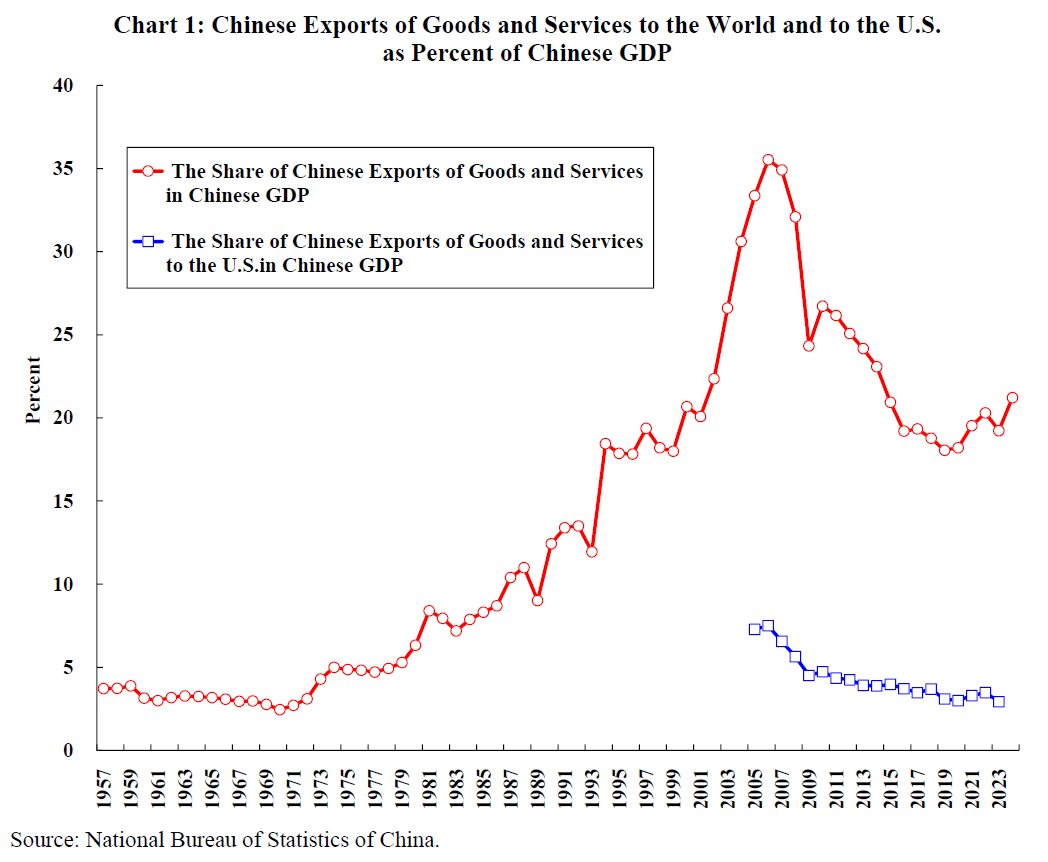

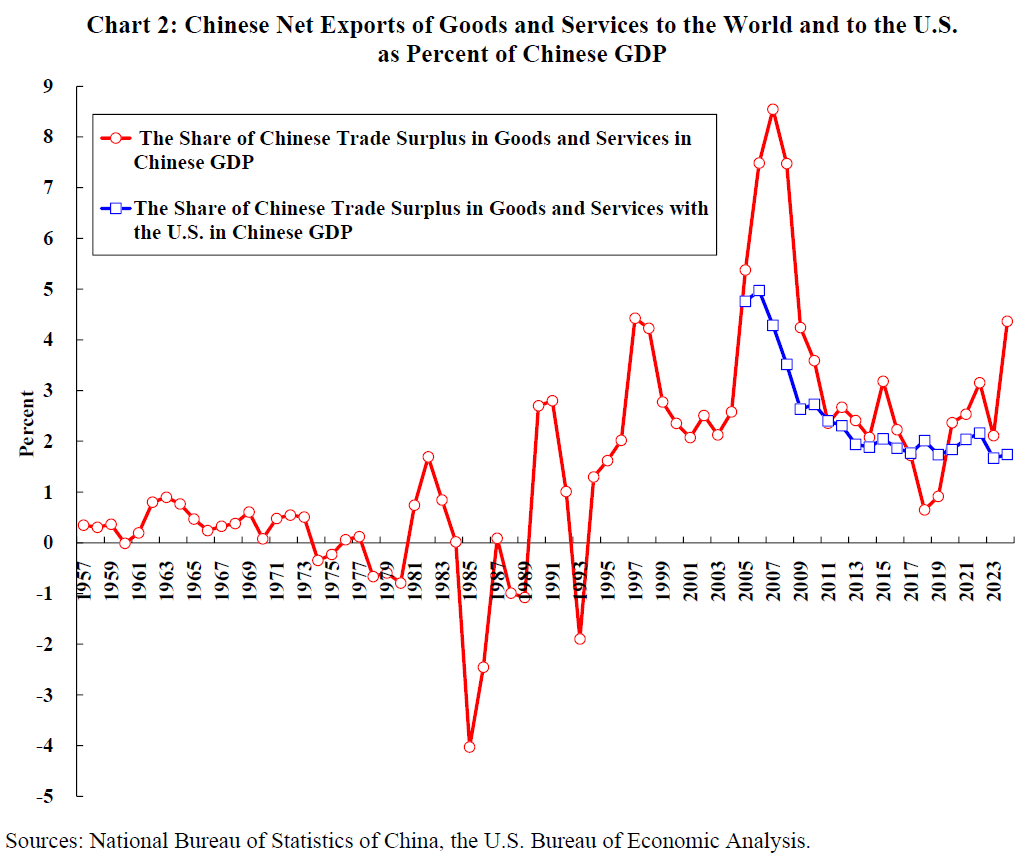

The dependence of the Chinese economy on exports and, in particular, on exports to the U.S., has declined significantly over time (and for that matter, so has dependence on foreign, including U.S., direct investment). Chinese exports of goods and services as a share of Chinese GDP was 21.2% in 2024, and 19.2% in 2025Q1, compared to a peak of 35.5% in 2006. Chinese net exports (trade surplus) of goods and services was 4.37% of Chinese GDP in 2024, compared to a peak of 8.55% in 2007. Chinese exports of goods and services to the U.S. was 2.9% of Chinese GDP in 2024, compared to a peak of 7.5% in 2006. (The share of Chinese exports to the U.S. in total exports is around 14%.) Chinese net exports of goods and services to the U.S. was 1.74% of Chinese GDP in 2024, compared to a peak of 5% in 2006. (See Charts 1 and 2.) The 2024 export numbers are probably higher than normal because of the acceleration of exports to the U.S. in anticipation of tariffs. All of this suggests that the impact of the additional tariffs on Chinese exports and hence on the Chinese economy is not as large as may be expected.

At the latest tariff rates set by both countries, 145% on U.S. imports from China, and 125% on Chinese imports from the U.S.,2 there is no possibility of trade because no enterprise in either country, whether exporting or importing, has the profit margin to absorb the cost of such tariffs. (For example, it is unlikely that Boeing can continue to sell its airplanes to China at a 125% rate of tariff if Airbus faces little or no tariff.) Trans-shipments through third countries such as Mexico and Vietnam to avoid the tariffs are unlikely to be successful because the “rules of origin” are expected to be applied stringently. Thus, the total cessation of bilateral trade will become the “new normal”, at least for a while, eliminating any trade surplus or deficit altogether. However, the recently announced exemption of “electronic products”, including cell phones, notebook computers and semiconductors, by the U.S., may allow around US$100 billion, or almost a quarter, of Chinese exports of goods to continue for the time being, reducing the short-term negative impact of the tariff war, but it is uncertain how long the exemption will last.

The value-added content of Chinese exports of goods to the U.S. has been increasing over time. It rose from 0.56 in 2010 to 0.71 in 2023.3 Thus, a US$1 reduction in Chinese exports to the U.S. implies a reduction of approximately US$0.71 in Chinese GDP. In contrast, the value-added content of U.S. exports to China has always been quite high. For example,

U.S. exports of agricultural goods to China such as beef, corn and soybeans have almost 100% domestic value-added content.

The damage of the tariff war to the Chinese GDP resulting from a total economic de- coupling with the U.S. may therefore be approximately estimated as the net trade surplus times the value-added content, 1.74% times 0.71 = 1.2%, other things being equal. 4 With the “electronic products” exemption, the damage may be estimated to be 0.9%. While there will definitely be turbulence and hardship in the Chinese economy, especially for exporters and for localities specialising in exports, there is little risk of a full-blown recession. The Chinese economy, with a rate of growth of around 5%, can survive a loss of its real GDP by 1.2%. It can also navigate among the disruptions caused by the tariffs because of its relatively complete domestic supply chains. Its exporters will explore domestic and other markets than the U.S., and import-substituting innovations, such as those undertaken by DeepSeek and Huawei, will be accelerated. In addition, China is likely to increase its domestic aggregate demand through public investment and public goods consumption to counter the decline in exports and to more fully utilise its excess production capacity, especially that idled by the tariffs.

In March 2025, China announced a target growth rate for 2025 of around 5%. The weighted average of the target growth rates of its individual provinces/municipalities/ autonomous regions announced in the first months of this year is 5.26%. This suggests that there is still some residual room for additional growth. The Chinese economy grew 5.4% annualised in 2025Q1, driven in part by the accelerated exports in anticipation of tariffs. I would venture to predict a rate of growth of around 4.5% (5.26 - 1.2 + 0.5) for the Chinese economy in 2025 under the tariff war, with 0.5% coming from the anticipated additional economic stimulus. If achieved, given the many uncertainties, it is a very respectable real rate of growth. For the decade beyond 2025, an average rate of growth between 5% and 6% for the Chinese economy is feasible. The Sky is Still Not Falling for China!

In the short term, some degree of de-coupling between the two economies is inevitable, lowering welfare in both. However, in the longer term, when all is done and settled, the net result is likely to be the emergence of additional supply chains in different parts of the world, which will enhance the resilience and stability of the entire global economy and perhaps even increase welfare. With multiple supply chains, the negative effects of disruptions due to geo- political conflicts, pandemics or natural disasters will be minimised and the increased market competition will bring about higher qualities and lower prices for all.

It is not clear what the ultimate U.S. goal is for its tariff war. The tariffs may be tied to other issues beyond simply trade, such as the access of Chinese-built ships to ports, capital control, the purchase of U.S. bonds, secondary sanctions, and the use of SWIFT for international settlement. Given all the uncertainties, China is better off pursuing its own economic policies independently of what the U.S. may or may not do. It should strive to be self-reliant and innovate independently, but not aim at achieving autarky or total self- sufficiency. Insofar as possible, it should continue to maintain openness not only with respect to its economy, but also in the fields of education and science and technology.

It is unlikely that the tariff war will end soon, but it is also unlikely to escalate into a hot war between the two countries, because such a war will have no winners, only losers. If the former Soviet Union and the U.S. could manage to avoid a hot war in the last century, China and the U.S. should also be able to do so. China-U.S. strategic competition will eventually end with both countries accepting each other as equals under the principles of peaceful coexistence, mutual respect, and win-win cooperation, and the relationship will be sustained by "economic interdependence“ as well as “mutually assured destruction”.

1. Ralph and Claire Landau Professor of Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, and Kwoh-Ting Li Professor in Economic Development, Emeritus, Stanford University. The author wishes to thank Dr. Mingchun Sun and Prof. Yanyan Xiong for their most helpful advice, assistance and comments. He is solely responsible for any remaining errors therein.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute.

2. The Chinese Government has indicated that it would “no longer respond” to any further tariff escalations.

3. Private estimates.

4. There is, in principle, a second-round effect from the reduction of GDP due to the reduction of exports. However, if the additional economic stimulus is launched in a timely manner, it will dominate the second-round effect.