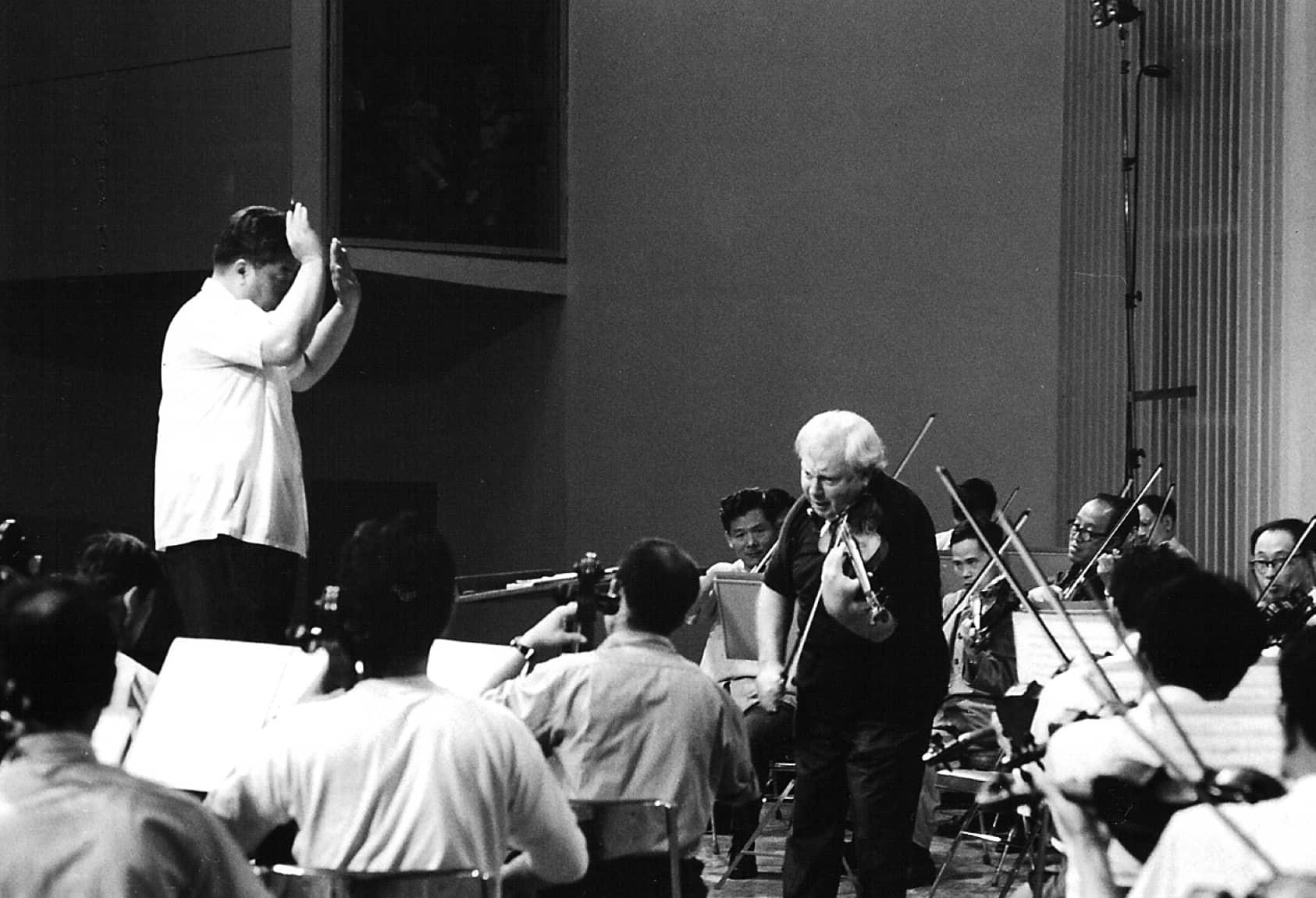

In Beijing, American violinist Isaac Stern appeared with the Central Philharmonic Orchestra in a concert that was televised like throughout China. (1980)

A conductor of a national symphony. A renowned violinist. A renowned pianist.

What brought them together was none other than the power of cultural diplomacy. Chinese conductor Li Delun, American violinist Isaac Stern, and American pianist David Golub together convened seven years after Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China.

In 1979, Stern and Golub were invited to collaborate with the China National Symphony Orchestra to perform a series of violin concertos composed by Mozart and Brahms. Not only was Li an intellectual co-creator, he was also the guide, translator, and companion to the two American guests. Amongst the many talented players in the symphony was the ten-year-old prodigy cellist Jian Wang, who went onto becoming the first Chinese musician to ever sign a contract with Deutsche Grammophon.

The collaboration was commemorated through the Oscar-winning documentary, “From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China.” Last October, I chanced upon a New York Times op-ed that read, “For the U.S. and China, It Starts with Listening”.

My interest was piqued. As I read through the thoughtful, compelling piece penned by Carla Dirlikov Canales, a singer, educator, and an Arts Envoy for the US State Department, I can’t help but recall the incredible journey and enduring legacy of Isaac Stern and David Golub, which exemplified in full the importance of cultural diplomacy.

As academic John Lenczowski put it in 2009, cultural diplomacy is the “exchange of ideas, information, art, language, and other aspects of culture […] in order to foster mutual understanding” between peoples. As I would call it, it is the conducting of diplomacy through identifying and sharing what makes us all human: a love and passion for the undying creativity that defines the human condition.

Cultural diplomacy allows for performers, audiences, theorists, and critics to cut through political and identitarian divides, to strike a common chord with one another. Through leveraging the inexorable and boundless energy of artists and creatives, cultural diplomacy reminds us of the fact: take away all the labels, categories, and divisive constructs, we could well be more similar than we think we are, even despite our differences in tastes.

Cultural diplomacy allows for the forging of bonds in the unlikeliest of places – whether it be the Bolshoi Ballet’s 1959 tour of the United States, which garnered rapturous popular response; or the avant-garde British duo Wham!’s 1985 tour in China, which featured prominently in the music video of their no. 1 hit “Freedom.” Indeed, a decade ago, I had the pleasure of meeting musician Mark Obama Ndesandjo in Shenzhen – the half-brother of an American president, but more importantly, an accomplished musician, author, artist who firmly believed in the power of music in bridging cultural divides.

Indeed, such forms of diplomacy are clearly valued by governments on both sides. Spearheading Beijing’s attempts to cultivate a more amicable and dynamic international image are Confucian Institutes, which have been met with both sincere praise and vociferous criticism over the years. Under Secretary of State Antony Blinken, the Biden administration has launched the Global Music Diplomacy Initiative, with the explicit mission to “elevate music as a diplomatic tool to promote peace and democracy.”

Yet as with all Track-1 and Track-1.5 diplomacy initiatives, these very efforts are inevitably constrained by one critical determinant – whilst affinity with the state brings with it sponsorship, access, and prestige, it also deters and wards off those who are wary of engaging with what they perceive to be foreign governments.

Track-2, civilian-led, diplomacy appears to be a more natural and compatible modus operandi and space for cultural engagement. Indeed, the New York Philharmonic toured Hong Kong and Taiwan last year, whilst the American Ballet Theatre returned to China in November last year, kickstarting its Asian tour in Shanghai. A two-day Chinese rock and folk music festival, ‘Friends from the East,’ took place in New York City in late November in 2023, drawing thousands of Millennials and Gen-Z fans.

These examples attest to the centrality of the “people-to-people ties that have bound the U.S.-China relationship together over decades of engagement” as discussed by a Brookings commentary penned by Professor Li Cheng and Ryan McElveen. After three years of pandemic-induced travel restrictions, cultural traffic is once again picking up across the Pacific.

Yet more can be done. For the genuine deepening of understanding and cultivation of empathy, the base of dialogue and participation must be widened to account for more voices. There are three tentative suggestions to this effect.

Firstly, private-sector actors should work in tandem with leading cultural diplomacy organisations, including the excellent Asia Society, in advancing newer forms of cultural collaboration and bricolage. A friend of mine set up a local Street Art hub in Hong Kong that is supporting an excellent performing arts crew that fuses breakdancing with lion dance repertoire. Why not the fusion of Cantonese and Italian opera, as one of my seasoned friends has asked and is earnestly exploring?

Leading Hong Kong-based art groups such as Zuni Icosahedron have sought to spearhead cultural exchange initiatives bringing together practitioners from all over the world, to engage in serious and invigorating conversations on how culture can be a bridge for shattering norms and deconstructing stereotypes. Philanthropists, educators, and arts patrons should be more open-minded about funding joint collaborations between arthouses and independent directors from Greater China and the US, thereby providing the ground and room for fledgling minds to find their own voices.

Secondly, cultural diplomacy must not take place in a vacuum. Policymakers, advocates, and lobbyists seeking to promote Sino-American cultural ties, must see to that culture both feeds into and is reinforced by other aspects of people-to-people exchanges, such as tourism, creative economy, education, and human talent policies.

There are few better ways of promoting a city, than to highlight and harness the spontaneity, originality, and uniqueness of its culture. In lieu of telling stories, a far more pragmatic solution would be to let the story unfold and play out before the eyes of visitors. Bring more tourists and visitors into a city for them to get a feel of the bona fide, on-the-ground culture.

From the flamboyant progressivism and enchanting grittiness of Chongqing to the neo-noir mystique of Chicago, city-to-city bonds and in-depth cultural tourism are both pivotal components of successful public diplomacy. As national-level diplomacy becomes increasingly gridlocked and enmeshed in caustic mistrust, it is all the more imperative that provinces and cities in China, and states and cities in America step up to fill the gap.

Thirdly and finally, it is high time that those who care about cultural exchange, spoke up about them. From social media platforms to private communications, we must spread the word. We should spread the love for culture, highlight the room and space for cultural initiatives to grow, and come to co-create and co-consume the gems of cultural exchange that have long sustained a salubrious bilateral relationship between the two peoples of China and America.

Politicians and geopolitics can be ugly. Yet culture can and should rise above the fray. For this to happen, however, all hands must be on deck. I remain hopeful.