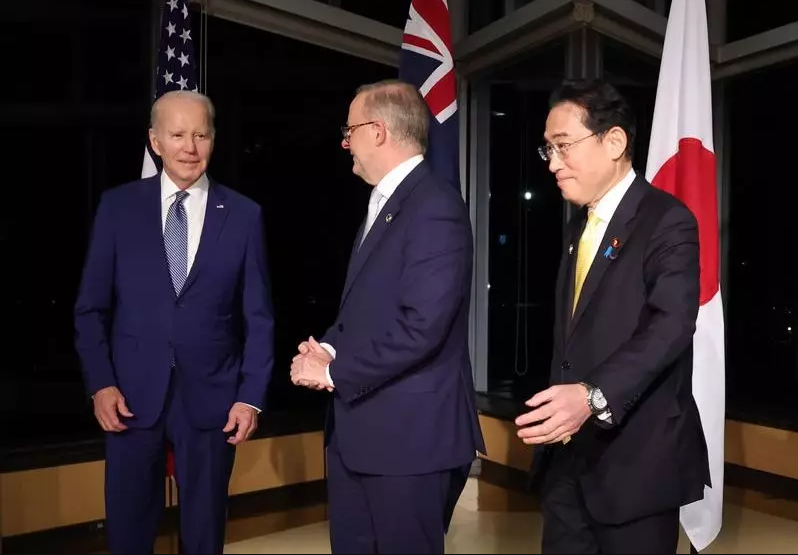

U.S. President Joe Biden made the announcement of a historic missile pact at the close of his bilateral meeting with Japan's leader Fumio Kishida on April 11 that the United States and Australia will develop an integrated missile defence system with Japan.

In recent years — and especially after the outbreak of the Ukraine conflict — the United States reached agreements with a few allies and partners to jointly produce weapons.

• In the Asia-Pacific region, it struck a deal with Japan to co-produce missiles and jet trainers;

• India will co-develop and produce Stryker armored vehicles;

• Australia will produce guided multiple-launch rocket systems and 155mm shells.

• In Europe, two U.S. companies are jointly manufacturing 155mm shells with Ukraine.

• Lockheed Martin, one of the largest defense contractors in the world, has established a production line in Poland to make F-16 fuselages.

• Northrop Grumman, another defense prime contractor, is exploring co-production of 120mm tank ammunition in Poland.

• In Germany, a Patriot-2 missile production line is being established.

These weapons systems will replenish U.S. military stocks or be delivered to the armed forces of host countries. Or they may be provided to third parties. The Patriot-2 missiles made in Germany, for example, will be delivered to Ukraine.

The United States has strong incentives to co-produce weapons. One is to address insufficient domestic capacity. After the Cold War, the U.S. military-industrial complex underwent severe atrophy, resulting in the bankruptcy and consolidation of a number of defense companies. It suffered from vulnerable supply chains and the loss of skilled workers, resulting in reduced production capacity.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, of all deliveries completed between 2012 through 2021 by U.S. defense firms, the average time between the sale announcement and delivery was about four years for air defense systems, three-and-a-half years for aircraft and two-and-a-half years for missiles. Sometimes, these delays stretched to nearly a decade.

The United States can only produce 450 Patriot missiles per year, with more than half of those allocated to the U.S. military and the rest sold to other countries. As the U.S. Department of Defense regards providing military aid to Ukraine as the top priority, orders from other clients have been put on the waiting list.

America’s second incentive is to provide business for U.S. defense contractors. According to the latest statistics by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, military spending has increased significantly over the past decade in regions such as Europe, the Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, with Ukraine increasing by a factor of 13. Poland is up by 181 percent, Germany by 48 percent, Australia by 34 percent, Japan by 31 percent and Israel by 44 percent, to name a few.

As a consequence of skyrocketing defense budgets, U.S. allies and partners have a greater demand for arms, and its defense contractors can make profits through technology transfers and outsourcing.

The third incentive is to support allies and partners materially. Located in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific, the aforementioned countries and regions are either in conflict, near conflict zones or likely to wade into conflict. The United States can make use of their sense of insecurity and help strengthen their military power and defense production capacity, reassuring them while reducing its own burden.

At the same time, those allies and partners also desire American defense technologies. By co-producing weapons, U.S. allies and partners typically achieve technological upgrades. Historically, South Korea’s defense industry kicked off with an authorization to manufacture the M16 rifle, and U.S. military co-production programs assisted Japan in developing its civil aircraft industry.

Last but not least on the list of incentives, the U.S. is trying to make defense co-production a deterrent to adversaries. The so-called integrated deterrence concept proposed by the Biden administration in its 2022 National Defense Strategy argues for the integrated use of military, political, economic and diplomatic means to safeguard national security and interests, expanding the scope of deterrent measures from the military to the economic domain.

The 2024 National Defense Industrial Strategy further emphasizes that defense production is part of integrated deterrence, implying that where there is insufficient defense production capacity domestically, joint production of weapons with allies and partners is highly valued.

Co-production of weapons has benefited both the United States and its allies and partners, but they must overcome some obstacles to achieve it. First, U.S. defense contractors are reluctant to transfer technologies, concerned about high-tech being leaked to third parties. Second, bureaucratic procedures for co-production are lengthy, and a co-production deal requires approval from the State Department, the Department of Defense and the National Security Council, subject to rejection by any one of them at any time. Third, populism and protectionism are prevalent in the United States these days, which is reflected in restrictive legislation passed by Congress in recent years on foreign-sourced products and technology transfers to foreign companies for fear of domestic job losses.

Once those obstacles are overcome and a co-production deal is struck, both U.S. defense contractors and their allied and partner counterparts will reap enormous profits. U.S. companies need not worry about production lines being idled, and investment risks can be transferred to their counterparts. Even if there is excess capacity in other countries, it will not cause significant losses to themselves. Allied and partner firms will also receive a large number of orders, profiting from lower costs, as production lines are located closer to the clients.

Additionally, allies and partners will become more dependent on the United States for security. Because of the long time frame needed to build out production lines and invest a large amount of capital in the purchase of technology, those allies and partners will be deeply bound to the U.S. India, for example, was once a traditional client of Russian arms, but with increasing arms purchases from the United States and the introduction of U.S. technologies, India’s security relationship with the United States will be further consolidated.

In conclusion, the increasing number of cases of co-production of weapons with its allies and partners indicates that the relative decline of U.S. manufacturing strength and national power has left it unable to support itself alone. But its desire to maintain global hegemony remains, necessitating support from allies and partners. Burden-sharing is no longer just about more funding for U.S. garrisons overseas or raising defense budgets but has expanded to include co-production of weapons.

However, co-production is bound to lead to more weapon proliferation across borders, aggravate security situations in various regions and increase the risk of conflict. The United States, along with its allies and partners, should stop playing with fire.