Four years after they last met in-person in Brasilia due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa convened in Johannesburg from August 22nd to 24th for a fifteenth and landmark BRICS Leaders Summit. The summit will long be remembered as the ‘expansion summit’, joining the 2009, 2011, 2014 and 2017 summits as the notable ones in the BRICS pantheon.

In 2009, the leaders of the BRIC countries met in Yekaterinburg, Russia, for their first-ever standalone summit meeting, elevating the BRIC grouping which had formally been established in September 2006 by their foreign ministers. Two years later in Sanya, China, the BRIC became the BRICS with the induction of South Africa. In Fortaleza, Brazil, three years later, the five countries established the New Development Bank (BRICS Bank) and their Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA). The Brazilian president at the time, Dilma Rousseff, is today the president of the BRICS Bank. And in Xiamen, Fujian province, China – the province that had once launched a hundred ships along the ancient Maritime Silk Road to the Middle East from its great ancient port city of Quanzhou, the Chinese chair introduced the BRICS-plus format in 2017 as a first step towards expanding the BRICS membership.

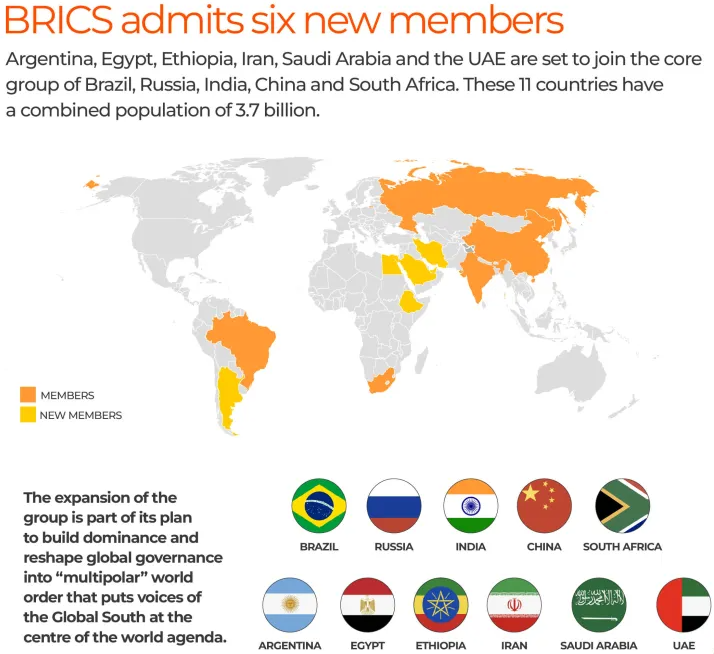

Fittingly, in Johannesburg at the fifteenth summit, the Middle East countries stand at the head of the inductees into the expanded BRICS grouping. Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Iran and Egypt along with Ethiopia and Argentina are to become full members of BRICS starting January 1st, 2024. The current expansion, furthermore, is not the end of the story. The five BRICS leaders have tasked their foreign ministers to develop a BRICS country partner model and report back at their summit in Kazan, Russia, next year with a list of prospective partner countries.

The induction of important Middle East and North African countries, many of which have internecine quarrels with one another, should not be seen as a liability to the grouping’s larger coherence and operation. Much like China and India could set aside their bilateral differences, even on the topic of BRICS expansion, the induction of conflicted neighboring countries should be seen as a strength – that is, as a commitment on their part to rise above narrower differences and champion an equal partnership of countries that share a common vision of a fairer world where the right to development and modernization is jointly defended. Like-minded, small cliques of countries that package their own rules as international norms is not the only or the preferred way to proceed in this age of global multipolarity.

Besides, many of the new BRICS entrants are not just fossil fuel-rich countries but may also be critical minerals-rich exporters that could be key to setting up end-to-end supply chains in a number of clean energy technologies. Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Iran and Egypt’s inclusion will also institutionally improve the relative underrepresentation of Muslim-majority states within the hallways of multilateral governance at a time when Muslims continue to encounter prejudice and intolerance in some parts of the world.

Looking ahead, the principles, purposes and ambitions that animated the four and thereafter five original members should serve as the principal doctrine for the expanded 11-member BRICS grouping.

First, the BRICS must retain its character - and core strength - as an association without compulsory elements and where every cooperative action flows from a common and conscious interest. There must be no recourse to litmus tests on intra-group cooperation. Bilateral frictions should be kept out of larger group dynamics. Geographic or functional issues where interests do not overlap should also be set aside, with the hope that they can be addressed positively another day.

Second, the original BRICS countries individually share the rare attribute of being among a select list of non-Western states which, with variances, can more-or-less afford the luxury of a certain independent-mindedness within the international system. This basic attribute should inform the criteria at the time of drawing up a list of prospective partner countries being considered for admission. Candidate countries must not be constituents of closed-ended alliance systems or have their security formally guaranteed by an external power. Indonesia, an internationalist and secular-minded Muslim-majority state with a defined doctrinal tradition of pluralism and independent mindedness, should be an obvious front-runner. As Nigeria gets its house in order, its induction too should be fast-tracked.

Third, the expanded BRICS must remain the premier developing country platform to pilot South-South cooperation. The New Development Bank should expand its unique imprint in the global development space by implementing faster loan approvals, operate with a lean organizational structure that results in lower loan cost, broaden the range of financing instruments at its disposal, and adopt country systems whenever possible to respond to local needs. The bank should also expand its membership and capital subscription base beyond the expanded BRICS countries. A ‘Friend of BRICS’ forum that invites members of the Global North to attend BRICS summits as a dialogue partner or a special invitee of the chair should also be mooted.

Fourth, the BRICS grouping must become the most important emerging market economy and developing country forum to discuss the overhaul of the international monetary and financing system. The New Development Bank should accelerate its work on trade invoicing and settlement in local currencies, diminishing the need to use established ‘vehicle currencies’ like the dollar and the euro. To this end, the bank should also increase its local currency financing as a share of its overall portfolio. Modernizing the IMF’s concessional financing facilities to adapt to today’s capital flow realities should be an important priority too. Concurrently, the BRICS should enlarge and convert their Contingent Reserve Arrangement into an Emerging Market Crisis Prevention Fund that is large enough to lean against sharp swings and self-fulfilling market panics. Over the medium-term, the BRICS should lead the effort to broaden the existing Special Drawing Rights (SDR) arrangements within the international monetary system, making its issuance automatic and regular.

Peering beyond the mere international monetary and financing system, the BRICS must also aspire to equip itself with the collective capability, down-the-line, to deter an external power or powers the means to weaponize the chokepoints of the global economy’s infrastructural plumbing to the grouping’s disadvantage. This could concern a transaction denominated in a ‘vehicle currency’, a product commingled with U.S. or Western-origin technology that is export controlled or, for the matter, a data packet that travels through a server or digital infrastructure located in and falling under the jurisdiction of that external country.

Finally, the BRICS should ramp up their political cooperation and speak in one voice on the important global challenges of the day. The purpose should neither be to splinter the international high table into rival political blocs nor soften the ground for the ‘Rest’ to wrest global leadership from the West. Rather, it should be to return the international system to the United Nations-centered moorings envisioned by its founders. As the Johannesburg Declaration notes, the BRICS seek to overcome polarity and division – not entrench it – and play its role in creating a world without barriers between North, South, East and West. For this to be the case, the expanded BRICS countries must also constrain their actions within the ambit of international law.

The BRICS stand at the cusp of a new and complex era in global politics. They must rise to the challenge with fairness and grace and restore a sense of community and equilibrium to the United Nations-centered international economic and political order.