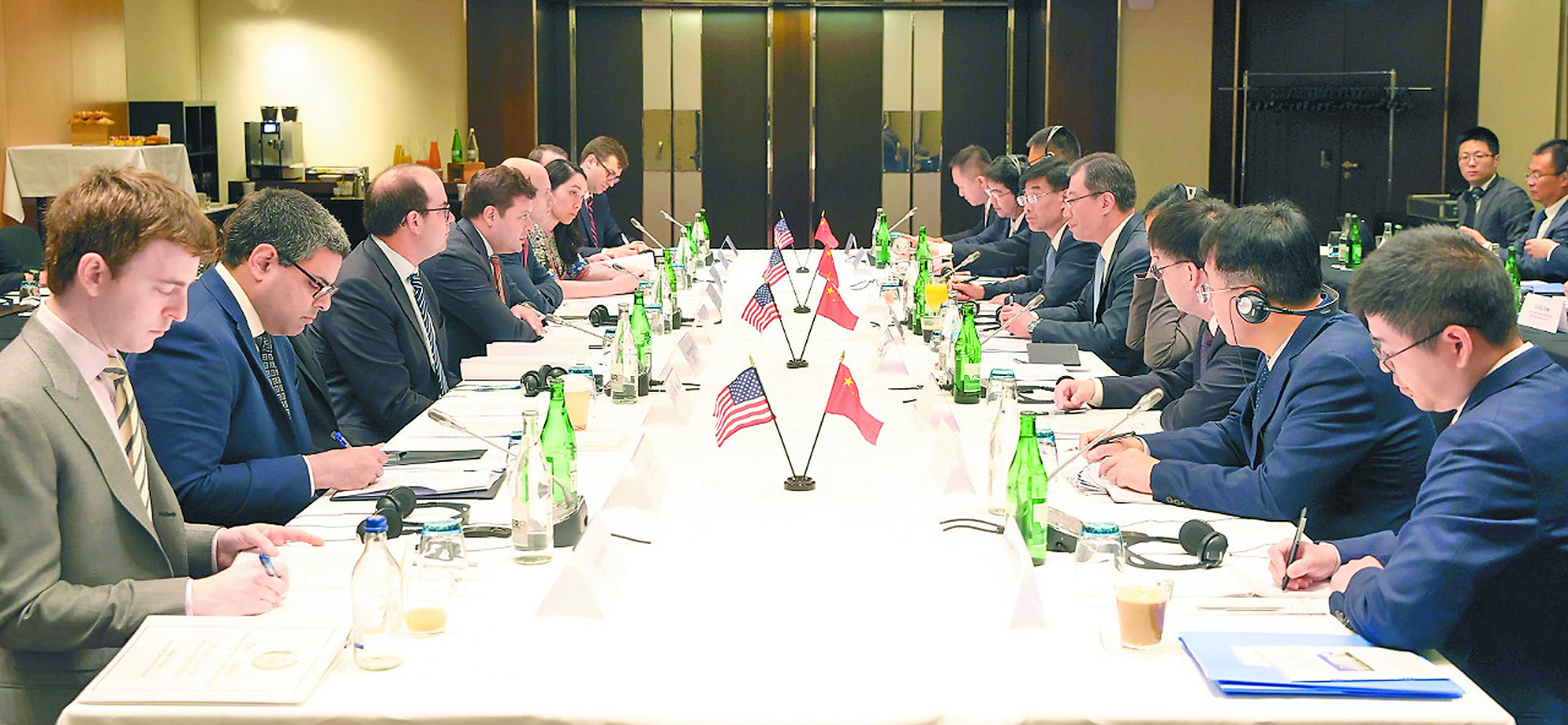

China and the United States held their first intergovernmental meeting on artificial intelligence (AI) in Geneva, Switzerland on May 14, 2024.

China and the United States held their first intergovernmental meeting on artificial intelligence (AI) on May 14. The session followed months of preparations between Chinese and U.S. representatives that culminated in a concrete commitment at last November’s Xi-Biden presidential talks during the November 2023 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit. As expected, the meeting did not yield concrete decisions, deliverables, or a joint statement, though both governments expressed satisfaction with an opportunity to exchange views.

In line with the Biden administration’s efforts to build “guardrails” against military conflict, U.S. officials termed such AI talks “an important part of responsibly managing competition” by helping make the world safer. Nathaniel C. Fick, the first U.S. Ambassador at Large for Cyberspace and Digital Policy, said the AI communication channel “will allow the United States and China to find areas to collaborate and work together, even as they compete in other areas.” Both governments participated in last year’s inaugural AI Safety Summit in the United Kingdom (which issued the so-called Bletchley Declaration, signed by both China and the United States) and this May’s follow-up summit in Seoul.

Secretary of State Anthony Blinken detailed the current U.S. approach toward emerging technologies in a presentation at last month’s RSA Conference in San Francisco, timed with the release of the State Department’s new International Cyberspace and Digital Policy Strategy.

According to U.S. officials, the strategy’s “north star – its organizing principle – is the concept of digital solidarity” among allies, partners, companies, and civil society actors sharing U.S. values. Blinken defined digital solidarity as “a willingness to work together on shared goals…to help partners build capacity to provide mutual support…to collaborate on everything from norms to regulations to technical standards.” U.S. officials argue that this focus on partnerships—also seen in Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s speech at the recent Shangri-La defense dialogue—contrasts with authoritarian regimes’ prioritization of “digital sovereignty.”

At the Geneva talks, the PRC representatives sought to reverse tightening U.S. limits on the transfer of advanced technologies to China. The Chinese government perceives the U.S. “small yard, high fence” approach limiting exports of advanced semiconductors having potential military or AI applications as excessively broad and restrictive. They instead proposed consideration of joint China-U.S. AI-related research and development projects.

The Chinese government also wants to strengthen the role of the United Nations in governing AI norms and rules, partly to prevent U.S. tech companies or the U.S. government from enjoying decisive influence on the issue. Such a stance, seen in the negotiations regarding a UN declaration on a Global Digital Compact, also aims to appeal to developing countries lacking leading AI firms. Though cooperating in UN bodies, U.S. officials have focused most attention on the G7, where China and Russia are not members. To compete with Beijing for Global South approval, Blinken and other U.S. officials have stressed their affirmative vision for using AI to impart momentum to lagging UN Sustainable Development Goals.

In a presentation at the Washington Post headquarters on June 6, Fick said the United States was interested in continuing its dialogue with China. For example, both governments can exchange information about how they are aligning frontier AI systems with human values. Though the U.S. approach currently focuses more on securing “voluntary commitments” by developers to subject novel technologies to rigorous safety and security reviews, which Flik valued for their flexibility in addressing rapid technological changes, the United States may move closer to the more regulatory approach of PRC authorities.

Still, the range and impact of these discussions will remain limited. Beijing has declined to sign the U.S.-authored Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy, which more than 50 other governments support but needs more backing to become an established norm of responsible international behavior.

The United States is unlikely to relax national security export and investment controls for U.S. technologies having military application. For the same reason, U.S. officials will continue to resist collaborating on technical development projects and may curtail Chinese access to U.S.-developed closed-source AI models. They also want to prevent foreign actors from exploiting AI technologies to interfere in U.S. elections. Analysts are concerned that AI tools will make such cyber manipulation easier and more effective. For example, AI might make “deepfakes” of politicians more realistic, enable precision targeting of specially constructed communications to discrete individuals, and make foreign messaging appear more authentic.

Furthermore, U.S. officials will continue to raise allegations that China is pre-positioning malware in critical transportation, power, and water infrastructure in the United States and other countries. Timothy D. Haugh, commander of the U.S. Cyber Command and director of the National Security Agency, said that Volt Typhoon and other PRC-linked groups sought options to disrupt foreign military intervention in potential military contingencies involving China.

Future bilateral talks on AI safety may involve higher-level officials from a broader range of government agencies, including defense departments. It could be beneficial to address AI issues in arms control and risk reduction dialogue between the Chinese and U.S. security communities. The two governments recently agreed to resume direct military talks.

Nonetheless, China and the United States are unlikely to negotiate a formal AI treaty anytime soon, while unilateral statements, even if made in parallel by both governments, will confront problems of verifying and enforcing compliance. Establishing an AI Incidents Hotline is of questionable value given problems with past Sino-American crisis communication mechanisms.

The most productive talks on AI and military security will likely continue to occur in non-governmental (Track II) dialogues concentrating on practice rather than principles. Past expert exchanges have clarified terminology, reviewed case studies, and, especially valuable, simulated potential AI-related conflict scenarios. Future sessions can profitably encompass academic and industry representatives.

One way or another, the two countries will continue engaging with each other on AI issues since they possess the largest AI companies and markets. At the same time, the commercial centrality of AI technology and its inherent dual-use nature ensure that AI issues will remain a source of tension between China and the United States.