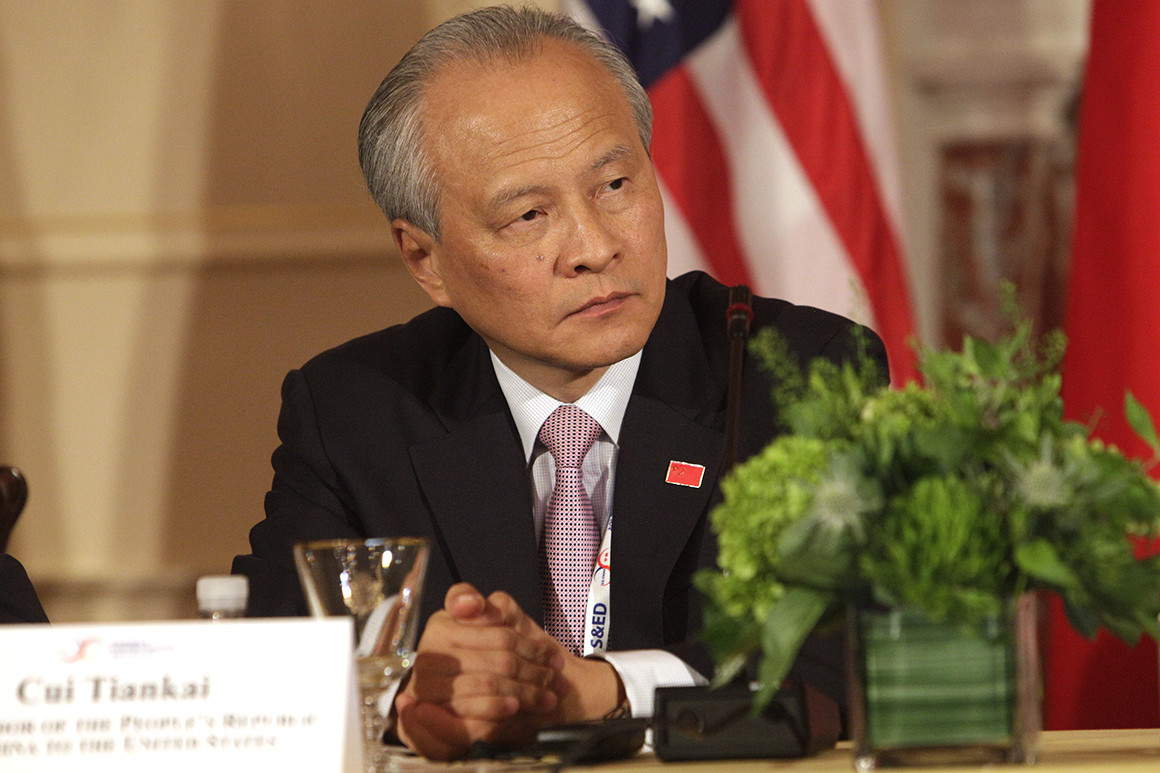

The Guardian reports that China's ambassador to the US said on Sunday he and other diplomats in Washington did not know which advisers Donald Trump turns to when forming policy on trade. Cui Tiankai was asked on Fox News Sunday if he thought the president is guided by moderates or hardliners. "You tell me," he replied. "Honestly, I've been talking to ambassadors of other countries in Washington DC and this is also part of their problem." Diplomats, Cui said, "don't know who is the final decision-maker. Of course, presumably, the president will take the final decision. But who is playing what role? Sometimes it could be very confusing."

Author Zachary Karabell opines in The Wall Street Journal that though Donald Trump defends his deployment of tariffs as a radical shake-up of world trade, he is using a dusty playbook. While the president certainly has the legal authority to impose duties, the statutes on which his administration relies are perilously out of date. They are based an economic order that no longer exists. Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act and Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act serve as the basis for tariffs on more than $250 billion of Chinese imports, as well as duties levied earlier this year on all steel and aluminum imports. Those laws were passed during the heyday of U.S. economic dominance—a time when access to American markets was essential to dozens of countries. From the end of World War II through the 1970s, the U.S. was by far the largest economy, the largest exporter of manufactured goods, and the largest consumer of foreign goods.But the relative stature of the U.S. in global trade has shrunk in the past four decades, as other countries and regions have become more affluent. In 1960 the U.S. represented 40% of global economic output; today it comprises barely 20%. This makes the Trump administration's unilateralist approach an anachronism—and not a winning one. Using laws and policies designed for an era that no longer exists is tantamount to deploying antiquated weapons in a modern war. In taking this unilateral approach, the administration ignores the vast multilateral framework that has emerged since the '60s. The World Trade Organization, which the U.S. helped create, imposes firm collective sanctions, and the U.S. has won more than 90% of the 123 WTO disputes it has filed since 1995.

The Wall Street Journal reports that The International Monetary Fund kicked off its annual gathering this past week with a stern warning about protectionism, downgrading its global growth outlook in part because of trade conflicts. But it ended it with central bankers and finance ministers taking a much less dire and confrontational tone than America's trading partners had after previous international meetings. Earlier meetings came against the backdrop of tough rhetoric from Washington about the trading practices of U.S. allies and open threats of new tariffs on cars. This time, officials gathering in Bali took some comfort from progress resolving many trade disputes even as a standoff between the U.S. and China has escalated. Speaking to reporters before departing Indonesia on Saturday, German Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann said he had seen "a certain change in mood," and recent breakthroughs like the trade agreement between U.S., Canada and Mexico "have made this scenario of an uncontrolled escalation a bit less probable."

- 2018-10-12 China’s trade surplus with the U.S. hit a record $34.1 billion in September amid trade war

- 2018-10-11 The Trump administration is right to redefine relations with China

- 2018-10-10 In New Slap at China, U.S. Expands Power to Block Foreign Investments Image

- 2018-10-09 Interpol Chief Was China’s Pride. His Fall Exposes the Country’s Dark Side.

- 2018-10-07 China Acts to Shore Up Economy Amid Weight of Trade War

- 2018-10-05 China’s Small Farms Are Fading. The World May Benefit.

- 2018-10-04 US and China are at risk of a '10- or 20-year' economic cold war, former Fed governor Warsh says

- 2018-10-03 The U.S. and China are playing a dangerous game. What comes next?

- 2018-10-02 Trump's trade victories mean the White House can now 'focus all its ire on China'

- 2018-10-01 Mattis Trip to China Canceled

- Bloomberg Trump Threatens Another Round of China Tariffs

- uk.reuters.com China property market feels fresh chill, 'winter' is coming

- www.theglobeandmail.com Canada sends rush of new exports to China amid US trade war

- Financial Times Tencent hit as China's freeze on new video game titles continues

- AXIOS.com China's brick-and-mortar economic stimulus

- New York Times Trump Embraces Foreign Aid to Counter China's Global Influence

- The Washington Post Who's Trump listen to on trade? Chinese ambassador at a loss

- The Guardian Relations with Pakistan remain stable, says China

- uk.reuters.com China regulator aims to protect small and medium-sized investors

- uk.reuters.com China says US arms sales to Taiwan interfere in its affairs

- Reuters At IMF meetings, China's globalization agenda left behind in trade debate

- www.theglobeandmail.com Globe editorial: China wants a free-trade deal with Canada, but the risks are many

- Bloomberg China Is the Climate-Change Battleground

- CNN Fareed: How Trump can win cold war with China

- Reuters At IMF meetings, China's globalization agenda left behind in trade debate

- qz.com A new $60 billion agency is the clearest sign the US is worried about China's Africa influence