Senator JD Vance (left) and Donald Trump during a rally on July 27, 2024, in St. Cloud, Minnesota. Trump has said that Vance has his full support as vice presidential nominee. Stephen Maturen/Getty Images

Ohio Senator J.D. Vance was recently announced as the Republican Party’s vice-presidential nominee. He is the first millennial on a major party ticket, and, if elected, he will be one of the youngest vice-presidents in American history. A former member of the U.S. armed forces, Vance also holds a law degree from Yale. He became nationally known in 2016 for his memoir, “Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis,” in which he attempted to explain rural America’s support for Donald Trump using his own background as an example. His first foray into politics was just two years ago, when he entered the Ohio Senate race.

Due to his short political history, Vance’s policy on China is not extensive, and in general, vice-presidents tend to have little impact on policy, though the close relationship that Joe Biden shared with Barack Obama as his vice-president was an exception. Regardless of if this will hold true in a second Trump administration, Vance’s China policy provides an interesting window into the contradictory nature of America’s China policy as a whole.

During his time in the Senate, Vance has authored a single bill on China, S. 3945, "To restrict the Chinese Government from accessing United States capital markets and exchanges if it fails to comply with international laws relating to finance, trade, and commerce.” He has coauthored a handful more, mostly bills for show that have only a few signatories and are not expected to make it past the floor. Notably, they are largely economic in nature.

Vance’s statements on China are similarly focused on economics. He has demonstrated particular concern about the threat posed by China's manufacturing to the U.S. economy and has called for a greater focus on East Asia and lesser on Europe. In his recent speech at the National Conservatism Conference, he said that “The dumbest of all possible foreign policy solutions and answers for our country is that we should let China make all of our stuff and we should fight a war with China…we should, in my view, not fight a war with China if we can avoid it, we should also not let the Chinese make all of our stuff.” The tone of this statement is vastly different from the rhetoric which comes out of the Hill and the current administration. It also resonates better with voters.

In contrast to what is shown in Congress, the media, or by other politically-involved groups, Americans in general are not driven by ideology when it comes to policies—though religious issues such as abortion and rights for the LGBTQ+ community tend to be the exception. Most Americans vote based on how they are directly impacted by the world around them, and how the people they know are voting. In a 2020 study from Yale, all but 3.5% of Americans were willing to excuse undemocratic behavior from their preferred candidates if it helped them achieve their political and policy objectives. Professed libertarians and progressives alike will vote for Trump because they are tired of paying high prices for gas.

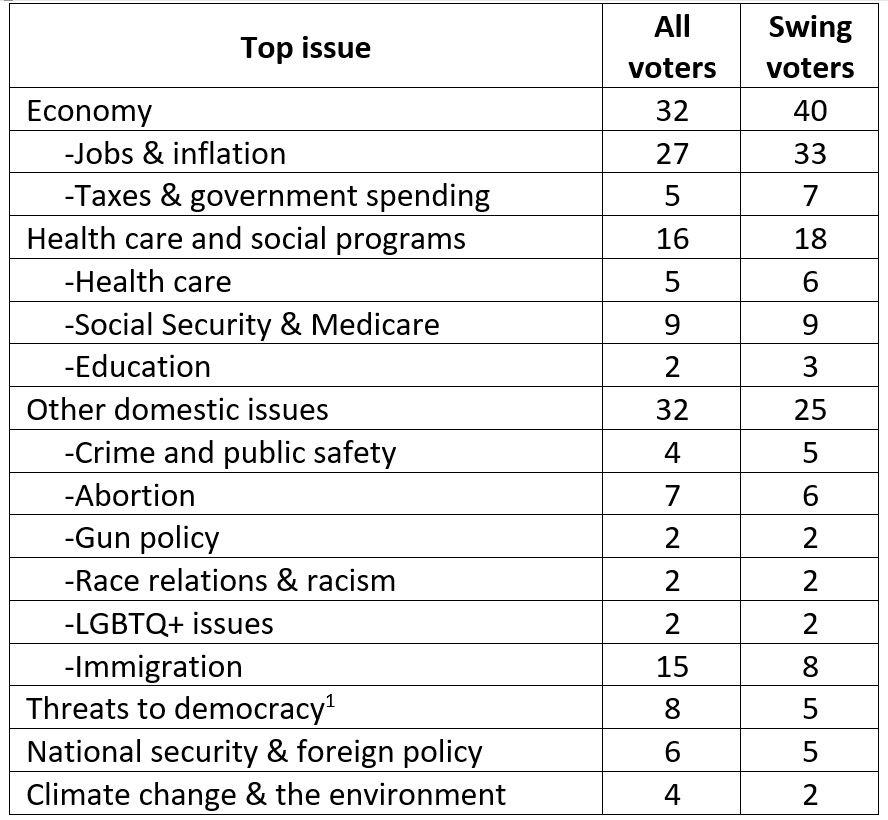

When asked directly, they offer support for Taiwan in the event of a full Chinese military operation, but they heavily prioritize the economy (32% of voters), health care and social programs (16%) and immigration (15%) over foreign policy and national security (6%). Like people all over the world, Americans may have grand aspirations about value systems, but when their basic physiological needs are under siege they will focus on safety, health, and economic security (See Table 1).

Table 1. Percent of American voters that prioritize each issue when deciding which candidate to vote for. From Data for Progress.

Moreover, when it comes to foreign policy, most Americans are open to direct diplomatic engagement with adversaries, even those with authoritarian regimes or records of human rights violations, as long as it benefits them. A Pew Research Survey from April 2024 that asked Americans about their foreign policy priorities found that the top issues were protecting the U.S. from terrorist attacks (73%), reducing the flow of illegal drugs into the U.S. (64%), and preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction (63%). Just under half of Americans thought that the U.S. should limit the power and influence of China, only 26% believed that the U.S. should promote and defend human rights in other countries, and a mere 18% wanted the U.S. to promote democracy abroad.

The question remains, if voters prefer pragmatism in foreign policy, why have politicians become increasingly ideological in their rhetoric on China?

Like Trump, Vance is no idealogue when it comes to China, but the ideology that he does subscribe to has implications for China. Vance’s story, regardless of its veracity, is a story that glorifies struggle as a personal value. His story is about more than just Vance overcoming obstacles—it is a critique of America’s lower-middle and lower classes for their failure to struggle enough. (Or, dare I say, a critique of their lack of 斗争精神.) In other words, if you’re not struggling, you’re not deserving of a good life.

Logically, it follows that if people do not have a good life but believe that they deserve one, they must be struggling against something. There must always be an enemy, there must always be an “other” to struggle against. Otherwise, people who believe Vance must accept that it is due to their own shortcomings that they cannot achieve what he did: the American Dream. And, of course, Vance (and many others) is happy to oblige, telling voters that “China has stolen a lot of American jobs,” and “impoverished hundreds of thousands of Americans.”

Ideologically, rhetorically, philosophically, Trump and Vance need the idea of China to struggle against. But practically, engaging in that struggle on a large scale would have huge negative economic repercussions which no American presidential administration can survive. Thus, Vance and Trump’s policy on China is left in a limbo from which there is no easy way out, as shown by the constant contradictory statements by Trump. Americans’ views on China are similarly paradoxical, as they see China as an adversary but do not prioritize it as one. Understanding this phenomenon means recognizing that U.S.-China relations cannot be built solely on shared goals, but rather on exchanging reciprocal compromises to ensure material benefits for each country in turn.

[1]This measure was worded as “threats to democracy” with no clarifying comments, which likely means it is comprised of both those for whom domestic threats to democracy are the top priority and those for whom foreign threats to democracy are the top priority.