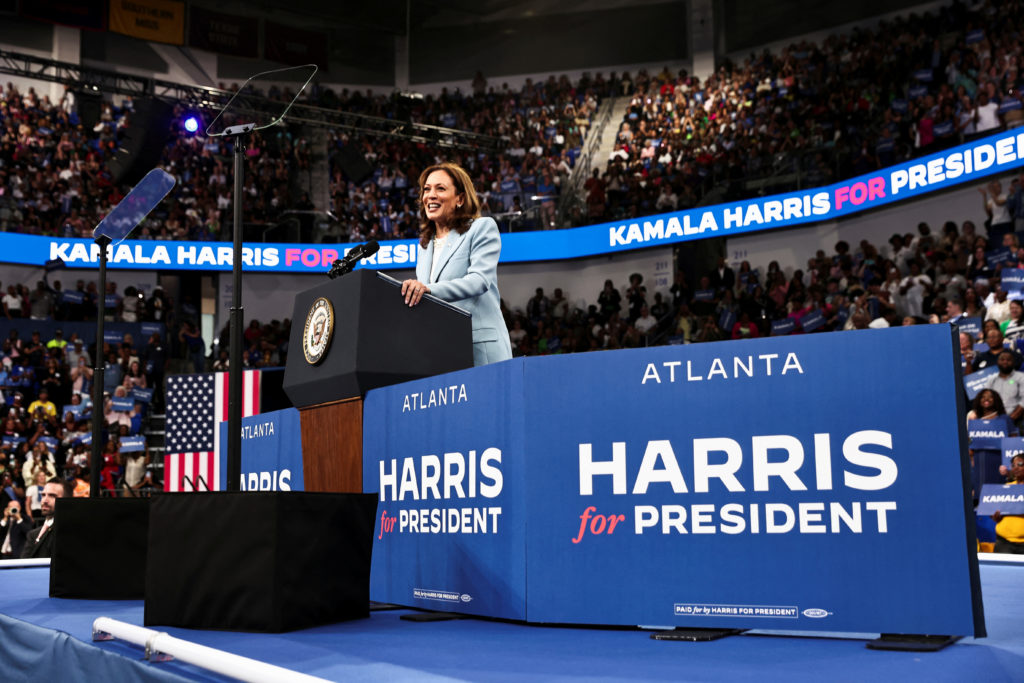

Democratic presidential candidate and Vice President Kamala Harris speaks at a campaign event in Atlanta, Georgia, July 30, 2024. Photo by Dustin Chambers/Reuters

Earlier this month, U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris received enough virtual delegate votes to be declared the presumptive Democratic nominee for president of the United States in the upcoming November election. After President Joe Biden stepped aside, Harris became the first black and South Asian woman to headline a major American political party’s presidential bid. She is running against former president Donald Trump, who is the Republican nominee. This article does not seek to evaluate the odds of Trump and Harris. What should be of much greater interest to anyone watching the Sino-U.S. relationship is Harris’s likely stance and approach toward China. While official materials published by her campaign have been notably sparse and lacking in detail, speculation and predictions abound among journalists over what some have dubbed the Kamala Harris Doctrine.

I hold the relatively straightforward view that many of Harris’s policies on China have yet to be published — not so much (or exclusively) because of a dearth of expertise or area-specific competence on her team but simply the fact that China is way down the list of pressing electoral issues. From the U.S.-Mexico border issue to abortion rights, and from navigating what scholar William Jacoby calls the “cultural war” waged between extreme right-wing conservatives and progressives on the left to articulating clear answers on the economy, the Harris team has had little time to prepare a complete manifesto. Given the myriad issues involved, it only makes sense that China has taken a backseat. This may annoy onlookers and investors who are keen on acquiring some semblance of certainty about the bilateral relationship going forward.

Sino-American dynamics

Those pinning their hopes for improved Sino-American relations on a Democratic victory in November — across presidential, congressional, state and local races — could well be disappointed. Eight years after Donald Trump took office, and more than a decade since Barack Obama unveiled his Pivot to Asia strategy, the U.S. political establishment at the federal level has developed a near consensus that typecasts China as a key strategic rival to compete against, confront contextually or even contain. (I found Stephanie Winkler’s genealogical exposition of the concept fairly helpful on this front.) From analogies to marathons, long games and even sharks, American pundits have jumped on the bandwagon with those who portray China as a menace — a notion that poses fundamental challenges to American ideological, strategic and economic dominance. The resentment cuts across partisan lines and is unlikely to go away anytime soon, regardless who occupies the White House come January.

Ultimately — and ironically — it is the scarcity of strategic clarity concerning the end vision, and an absence of a clear game plan or practicable modus vivendi, that has kept the U.S. locked in vicious vacillations between hysteria and complacency on China. China is viewed at once as easily defeatable and an insurmountable foe; both a weak and internally unstable state and an economic juggernaut that can usurp America’s purported dominance. Given the state of domestic political polarization, vitriol and innate mistrust between Republicans and Democrats, if Harris becomes president she would likely want to maintain continuity — with “acting tough, speaking tougher” as the overarching anchor of her country’s China strategy.

Much of this is to say that a Harris presidency would likely feature a continuation of Joe Biden’s preexisting options, which in turn carried on with implementing many of the initiatives introduced under Trump. Those include ramping up trade barriers and protectionism targeting Chinese companies, doubling down on the framing of the Sino-American rivalry through “values-based lenses” and ratcheting up the rhetoric concerning what America construes as issues of concern when it comes to civil and political liberties in China.

Just as Chinese diplomacy is increasingly geared toward satisfying the nationalistic and status-seeking preferences of vocal domestic audiences (as I argued in an article four years ago), American diplomacy is precipitously oriented toward the spectacle of a meta-narrative framed around a battle of narratives, and the reductionist yet effective lens of good vs. evil. One could be forgiven for being pessimistic.

Possible Harris difference

Yet in the same way that Biden provided far more stability and certainty regarding China than his predecessor, as well as a significantly more multilateral and institution-based approach to deal-brokering and ally-courting, it is likely that Harris would eventually come to imbue her own views and judgments with a recalibration of the U.S. approach to the bilateral relationship. Radical policy departures from the status quo are unlikely, but fine tweaking and moderation can be expected. We need not be deterministic.

There are several ways in which such variations could play out:

First, Harris will likely exert more effort to tackle racial discrimination against Asian Americans, as well as rhetorically emphasizing the distinction between the state and the people, and the people and the diaspora. Having served as both attorney general and senator for California, Harris and her team have long-standing connections with key Asian-American Pacific Islander (AAPI) players and advocates in the San Francisco Bay Area. They have sought to position her as a progressive who is well aware of the barriers and challenges posed by ethno-nationalism and anti-Asian racism.

There may be a more proactive effort to roll back the devastation wrought by the overzealous prosecution of the China Initiative by the FBI, as well as an emphasis on rekindling engagement and communication channels between the White House and key advocacy by Chinese-Americans.

Second, while Harris will continue to champion what she construes to be election-winning and image-bolstering “rights-based concerns” — as evidenced by the variety of bills she advanced as a senator, including one that was co-sponsored with China hawk Marco Rubio, a Republican — she will likely do so while playing up the room for economic and financial synergy with China.

With an economic recession possibly looming on the horizon and a stubbornly high youth unemployment rate, Harris is well aware that a stable, predictable economic trajectory is crucial for ensuring a soft landing. Avoiding a hot conflict with China, getting Beijing on board when it comes to American bond purchases and general macroeconomic stabilization are all integral to her accomplishing her domestic objectives.

Third, and perhaps most important, the Harris campaign is leaning heavily into Gen-Z and Millennial voters to turn out on election day. If she wins, the backing of these generations (who will come of age or develop sizable economic heft during her four-year term) would prove even more instrumental as she plans, presumably, for a reelection bid in 2028. Indeed, Harris’s enduring relations with Arab-Americans and young voters are shown by her comparatively nuanced and somewhat reserved position on the war in Gaza.

A Pew Research survey this year found that younger adults in the United States are by far likelier than their counterparts to view China as a competitor/partner, rather than an enemy. Such results are by no means grounds for relief in China, although do appear to suggest a more substantial basis for measures aimed at partial moderation and deescalation coming from the White House.

As a President Harris strives to push forward domestic policies on issues ranging from climate change to the regulation of artificial intelligence, there is much that she stands to gain from a more stabilized and robust Sino-American partnership — one founded not on pillars of jingoism and mutual strategic mistrust but instead on strategic co-dependence.

Those hoping for improvements to Sino-American relations should remain realistic about the slim odds of that happening in the short to medium run. Yet this does not mean that civil society, academic and business groups should not try — and they certainly should under a Harris administration — to reinvigorate and reignite the debate over the kind of comprehensive engagement strategy the U.S. needs. This could prove critical in managing its relationship with its foremost rival, partner and counterpart in Asia today. It remains to be seen as to whether Harris can, in fact, deliver.