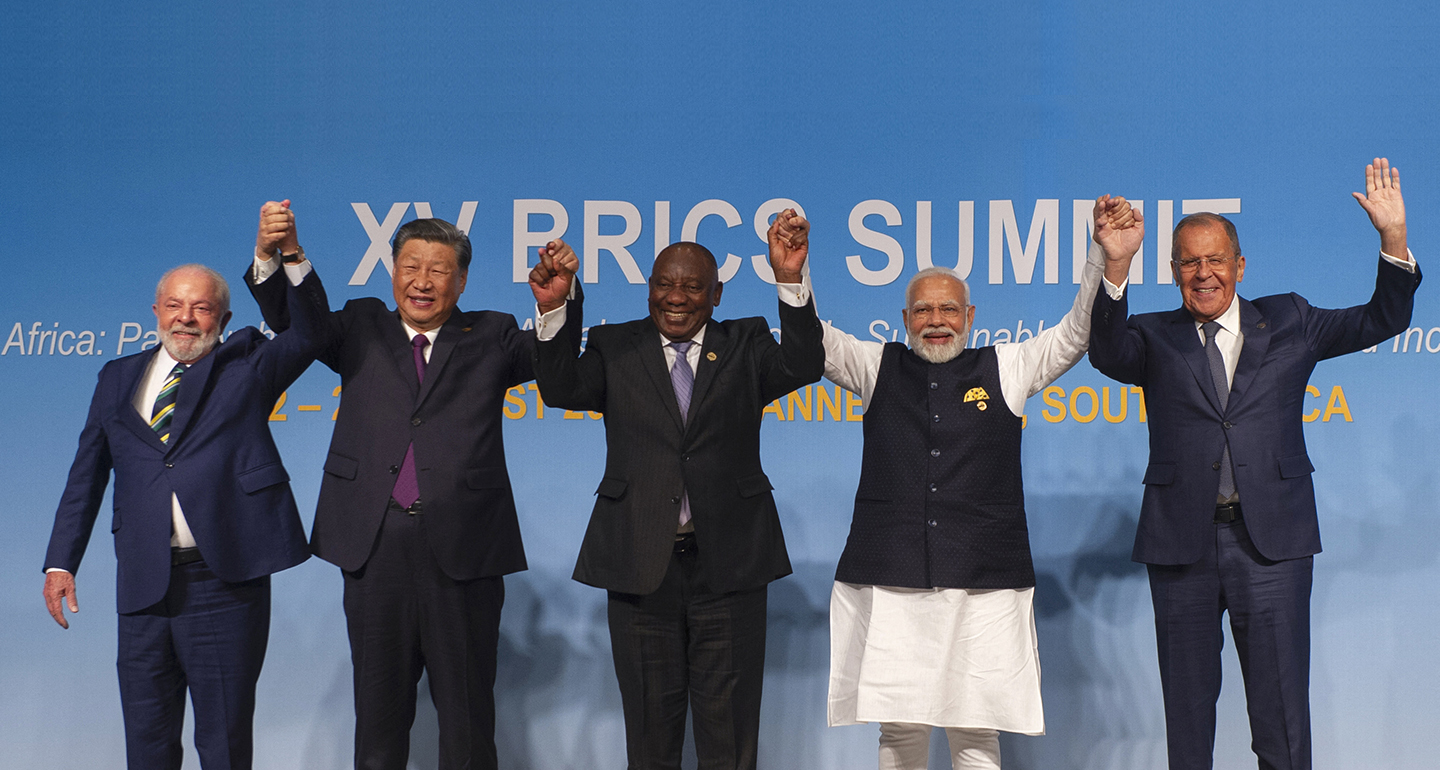

Leaders from the original BRICS countries raise their clasped hands at the 2023 BRICS summit.

While its exact definition may vary slightly, the Global South has established itself as a force representing Asian, African and Latin American countries at different levels of development, along with the established powers of the West, represented by Europe, the United States and Japan. It poses new challenges both to the global market and to global governance. Amid seismic changes, the developed countries’ positions diverge. But how the United States, the founder and defender of the existing order, deals with this new dynamic has particularly meaningful implications.

Changes in trade and economic relations are most notable. Over the past two decades, the rise of the Global South coincides with declining trade relations between the United States and the developing world as a whole. In 2006, the U.S. was a major trading partner of nearly 130 countries. A decade later, in 2016, the number had fallen to 76. By 2021 it had sunk to 49, with most of the decline happening in Latin America, a close neighbor of the U.S. and few countries from elsewhere. A number of American. think tanks, including the RAND Corporation, Carnegie and the Heritage Foundation are saying that the United States is losing the developing world. It is clearly losing the Global South.

The trend is most visible in sub-Saharan Africa. Ideas such as “Africa Rising,” the “Africa Miracle” and “Continent of the Future” speak to the enormous potential in Africa’s development. Intensive state visits, multilateral summits, upgrading of bilateral relations and economic agreements have become almost daily occurrences in Africa. Since 2010, more than 150 embassies have been established in the sub-Saharan region, and global cooperation with Africa has been strengthened across the board in the areas of trade, security, diplomacy and other areas. Between 2010 and 2017, more than 65 countries stepped up their trade with the region, and countries from East Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the Middle East, are rushing to ride the tide of Africa’s development. Former Brazilian president Michel Temer has identified Africa as a “permanent priority,” reflecting the sentiment of many countries.

But the United States has been quite oblivious to the change. Instead, it has withdrawn from sub-Saharan affairs and cut foreign aid and troop numbers. From 2010 to 2020, U.S. trade with Africa was halved, from $80.3 billion in 2010 to $36.7 billion in 2017 — less than one-fourth of China’s trade with Africa. Compared with other developed countries, U.S. trade growth with Africa is among the lowest.

U.S. President Joe Biden has changed course and amended some of Donald Trump’s inappropriate comments on Africa, but there is nothing new in terms of specific policies. Fundamentally, America’s perception of the investment and aid relationship is not aligned with the changing world situation. It has long helped underdeveloped countries through aid, with 35 percent of the total flowing to health, food security, agricultural production and basic education. But it is long-term development that requires investment and trade, which accounts for only 5 percent of the funding, a serious imbalance for recipient countries.

This indifference on the part of the United States may reflect its arrogance to some degree. Other developed countries have taken a different path and have made the transition much faster, gaining footholds in the African market by being more diplomatically active and more inclined to work with China to promote the continent’s development.

Why has the United States turned a blind eye to the burgeoning market potential of the global South? In large part, this is the result of its strategic perceptions stemming from the pan-securitization of foreign policy, which has dominated its approach to the Global South. An early and typical example of this is the confrontation with China’s Belt and Road Initiative. While loyal allies such as the UK and Japan have long since shifted to cooperation, U.S. opposition has remained a constant.

U.S. strategic anxiety about China’s rise has global implications that are evident in both the Global North and South, with pressure on Southeast Asian countries particularly pronounced. Southeast Asia is where the Belt and Road and Indo-Pacific Strategies converge, so taking sided with either the U.S. or China is an unpalatable option. Countries in the Middle East, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America and other regions are all feeling similar pressures to varying degrees, and even the Pacific Island countries are not immune.

But in today’s new context of pluralism and de-centralization, diplomatic coercion is bound to backfire. The United States asks countries to take sides in the Russia-Ukraine conflict and has generated resentment and resistance from the Global South. As a study by the European Commission argues, the conflict united the West but pitted it against the rest of the world. The same is true of the Coalition of Democracies, which was initiated by the U.S. In essence, America is departing from the prevailing trend of the times, which is reconciliation and development, and letting strategic anxiety drive its diplomacy.

The backlash against U.S. diplomatic coercion must be reckoned with. Many countries in the Global South have clearly expressed their dissatisfaction with the United States. Southeast Asian countries are under the most pressure and have the strongest discontent. “Don’t make us choose sides!” has become a common theme in the region in recent years. In the Middle East, China’s success in brokering the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement is another reflection of the fact that U.S. paranoia has made it difficult for it to gain the trust of regional countries.

The U.S. approach has not only cost it the Global South but has also created divisions within the Global North. Indeed, in both the North and South the approach is encouraging regional powers to pursue strategic autonomy and influence more aggressively — and the uncertainty of the regional situation is therefore increasing. This uncertainty, in turn, will further erode America’s global dominance. In short, the United States is losing not just the Global South but the entire world. This may be the inevitable fate of all empires: In the end, their inherent anxiety, paranoia and arrogance sends them to the graveyard of history.