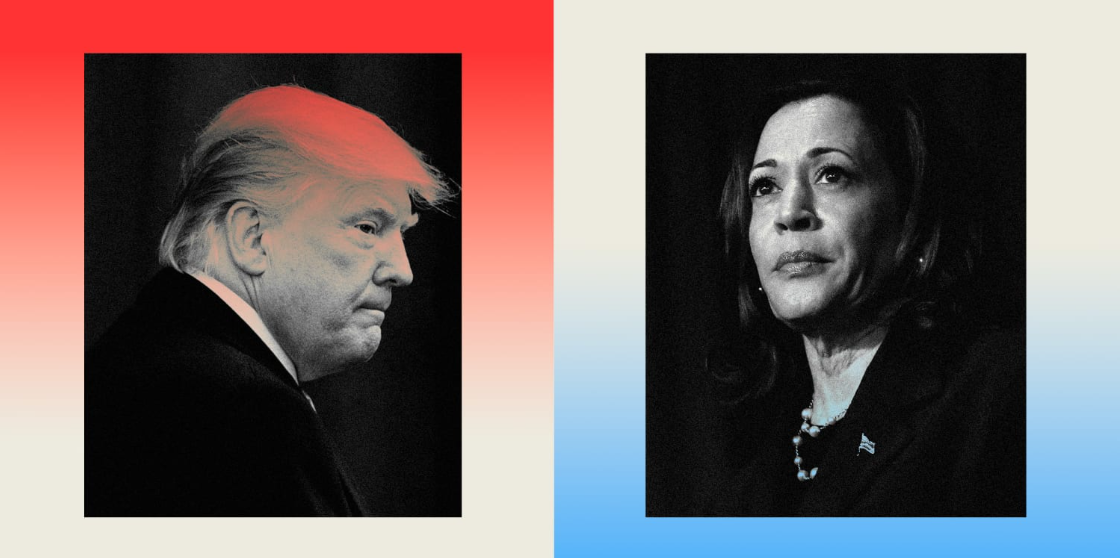

Now that the 2024 U.S. presidential campaign and election has been turned upside down by Vice President Kamala Harris’ replacement of President Joe Biden as the Democratic Party’s candidate, and former President Trump’s surprisingly strong poll numbers, it is timely to ask: what might the differences in U.S. policies towards China be if either candidate wins the election?

It is tempting—and not probably inaccurate—to surmise that both candidates and their administration’s previous China policies would be a good guide to what each would do if they returned to the White House. After all, each has a four-year track record of a fairly coherent and sustained set of China policies. The single most notable aspect of the two administration’s China policies has been their consistency and continuation. Their differences have been minor and more a matter of degree than fundamental substance. There has been a “through train” of China policy in virtually all areas of policy—diplomatic and political, military and security, economic and commercial, political ideology, cyber and espionage, technology, education, human rights, and other domains—there has been essential continuity from the Trump through the Biden administration. While the rhetoric has varied, the substance of policies has not changed much.

There have been a few differences. President Trump and his senior administration officials were much more critical in their rhetoric than President Biden and his senior officials have been. Trump and his administration offered many public condemnations of China—whereas Biden himself and his officials have offered fewer. They also produced several comprehensive statements on China policy. The Trump administration had a much more sophisticated public diplomacy approach to China than the Biden team has had. The Biden administration, by contrast, has done far more to strengthen alliances abroad and build coalitions against China than the Trump team ever did, while at home Biden has worked with Congress on passing important legislation intended to strengthen the American technological, educational, and research infrastructure to effectively compete with China.

Thus, the first thing we can anticipate is further continuity with the past eight years of China policies. China should not expect significant changes. Four years ago, some America watchers and officials in Beijing anticipated that President Biden would break with Trump’s radical shift on China and return to the previous policies of “engagement.” They were proven dead wrong (and it revealed a fundamental intelligence failure by China’s America specialists), and they will be proven wrong again if they think that U.S. policy is going to revert to the pre-2017 cooperative policies of “engagement” with China. Comprehensive competition is here to stay is the guiding stratagem for the U.S. Government.

Nonetheless, there could be some differences of degree between Trump and Biden/Harris 1.0 and 2.0. First of all, a President Harris could well be different than Vice-President Harris. We should not assume a simple continuation of either policies or personnel of the Biden administration. Similarly, a second Trump administration may also contain some changes and surprises.

The Prospects for a Second Trump Administration’s China Policies

For Trump’s part, he personally is the biggest wildcard because of his demonstrated unpredictability. Although he and his administration were, after their first year in office, highly critical of Chinese Communist Party and government policies, as well as critical of Chinese leader Xi Jinping himself, Trump 2.0 could abruptly pivot and reach out to Xi in the same way he did towards North Korea’s Kim Jung-un. Recently, at a July 21 campaign speech in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Trump used fawning language and made clear his respect for Xi—describing him as “brilliant,” “smart,” and “a fierce person because he controls 1.4 billion people with an iron fist.” If he tried such a gambit to orchestrate some kind of rapprochement directly with Xi Jinping, Trump would be putting himself deeply at odds with the entire Republican Party, his own administration, many in Congress, most Democrats, and most American citizens—all of whom view China as America’s No. 1 competitor and adversary.

Concerning America’s support for the defense of Taiwan, Trump has indicated that he views Taiwan in the same financially transactional way he views NATO allies: “Taiwan should pay us for defense; You know, we’re no different from an insurance company,” Trump told Bloomberg in a July 17, 2024, interview. It is difficult to know if Taiwan could “buy” renewed commitments for its defense from Trump and his administration, and what this would mean in practice.

A Trump administration trade policy would likely be a doubling down on the aggressive one he adopted the first time around. China, the world, and America’s own economy should prepare for considerable stresses (and inflation) from an even tougher tariff policy.

If Trump were elected, there is also the important question of who would serve in his administration that could impact China policies and what impact would their views might have? At present, I can only identify two—possibly three—individuals as on board the Trump train: his former National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien, former U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, and possibly former Deputy National Security Advisor and China expert Matt Pottinger. O’Brien and Pottinger are ideological hawks with deep antipathy for China’s regime, while Lighthizer is an aggressive trade hawk. Former Congressman and uber China hawk Mike Gallagher could also possibly get a senior position, as could Senator Marco Rubio (another China hawk who Trump considered as his vice-president). At this stage, it is hard to identify others who might be tapped for a second Trump administration in the security/defense realm but keep your eyes on Elbridge Colby (The Marathon Initiative), Oriana Skylar Mastro (Stanford University and Carnegie Endowment), and Zack Cooper (American Enterprise Institute). All three are China defense hawks.

Prospects for a Kamala Harris China Policy

As Vice-President, as far as we know, Harris has not been involved in formulating China policy. But she was a dutiful and disciplined “implementer.” That is, she made several trips to Asia (but never to China), she delivered few speeches that touched on China, and she closely stuck to her “talking points” in meetings with foreign officials. She apparently did not interact at all directly with Chinese officials in Washington or third country venues, although she did briefly meet with Xi Jinping on the fringes of the November 2022 APEC meeting in Bali, Indonesia. On January 27, 2024, she similarly met momentarily with Taiwan’s new President Lai Ching-te at the inauguration of Honduran President Xiomara Castro.

While she has not focused on China, Harris has been very involved with the Indo-Pacific, notably with Southeast Asia. Altogether, she has visited Southeast Asia five times and the Indo-Pacific seven times as Vice-President. On each occasion she gave carefully choreographed speeches, sticking closely to Biden administration policy language. One example was her August 24, 2021, speech in Singapore, which included some tough words concerning China’s illegal island occupations in the South China Sea. Her very carefully scripted speeches and all of her public remarks concerning the Indo-Pacific over the past four years apparently belies a deeper personal, intellectual, and cultural interest she is said to hold about the region. Similarly, Harris’ own personal heritage and affection for India augers well for a strengthened U.S.-India partnership. Given the importance of Southeast Asia in Washington’s China strategy, we can anticipate a continuation—if not an elevation—of attention to the region in a Harris presidency. This would be welcome as it has long been neglected (see here).

On other China-related issues, Harris does not have much—if any—of a track record. One area where she does concerns human rights. As Senator she co-sponsored the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act in 2020, and she was active in introducing legislation to protect human rights in Hong Kong and sanctioning Hong Kong officials. We might anticipate a tougher human rights stance towards China (something the Biden administration has seemingly abandoned since its first year in office).

Thus, much remains unclear about Kamala Harris’ thinking and approach to China. In this context, one should not dismiss the fact that she comes from California—a state with a strong record of engagement and commercial ties with China (dwarfing all other states California led the nation with $138 billion in trade with China in 2023), and it has a politically influential Chinese-American community (many of whom are pro-China).

Another uncertainty concerns the officials who Harris might surround herself with if she became president. Would she retain members of the Asia and China team from the Biden administration? Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell is the key person to watch, as it is possible that he could be elevated to the position of either National Security Advisor or Secretary of State. Campbell has been the principal architect of China and Indo-Pacific policies in the Biden administration.

In addition to Campbell, one key person to watch—and one key unknown—is Harris’ foreign policy advisor over the past four years: Phillip Gordon. Gordon is a much-experienced Democratic Party foreign policy insider who has served in multiple administrations and think tanks, with substantial expertise on Europe (he is fluent in French) and the Middle East. But he has next to no track record on Asia or China (his public comments, following those of Vice President Harris, in Singapore on August 24, 2021, were hesitant and superficial). Yet, Gordon might be a leading contender to become Harris’ National Security Advisor, as they have worked closely together over the past four years. Another notable candidate for high office (possibly Secretary of State) is Nicholas Burns, the Biden administration’s Ambassador to China. It is uncertain what views Burns would bring back following his four years of service in Beijing, but they have clearly hardened during this time. Burns is a deeply experienced and highly professional diplomat, and he now possesses considerable first-hand experience (much of it not so pleasant) with China.

Several other members of the Biden China team have already departed from their positions (at the National Security Council, Department of State, and Department of Commerce)—and thus a new group would fill the senior positions in several government departments. There is no shortage of knowledgeable younger China specialists in and outside of Washington who stand ready to populate a Harris administration.

Wait Until January 2025

While these speculations might open the aperture somewhat on what either a Trump 2.0 or a Kamala Harris administration’s China policy may look like, there is still much time before both the November election and before either would take office in January 2025. During this interim period there will be much jockeying for position within both camps, and both candidates and their campaigns will be pressed to specifically formulate and publicly articulate what their China policies would be.

As in all previous presidential campaigns, being “tough on China” can be expected and is a winning strategy with the electorate—and we can thus anticipate considerable criticisms to come over the next three months. China, too, is an actor and possesses its own agency—but Beijing cannot help itself, cannot improve China’s image in America, and can only further hurt itself through its words and actions.