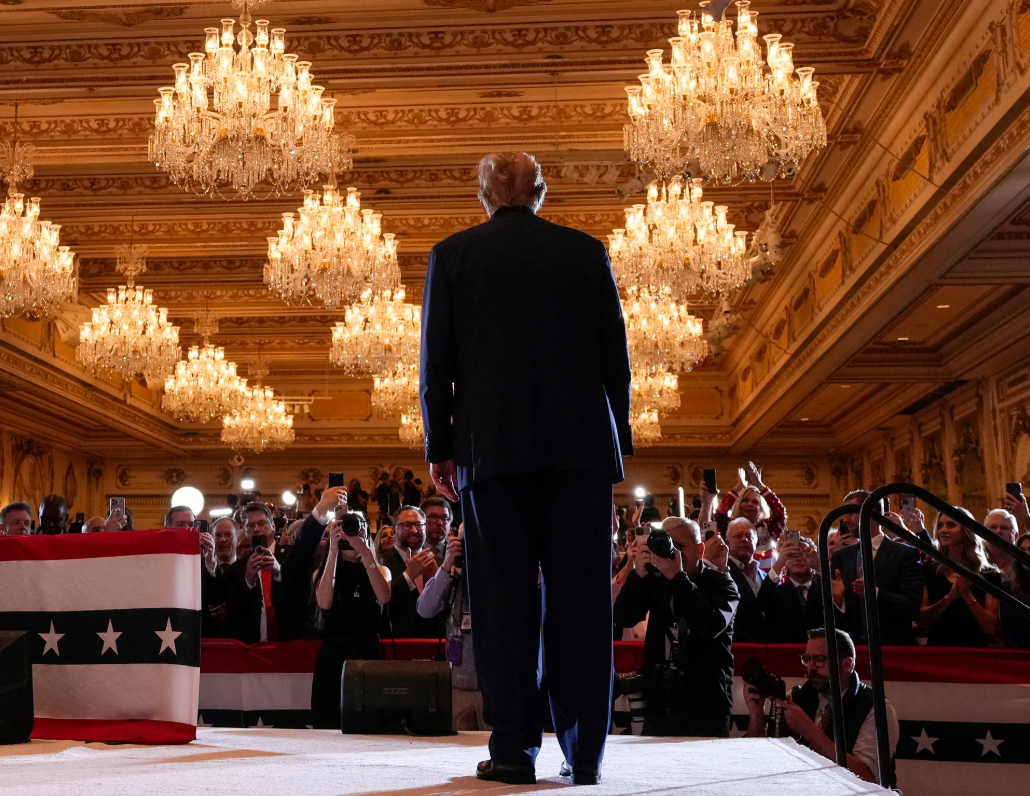

Ever since Donald Trump won the 2024 presidential election in the United States, his home and political base — Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, Florida — has been a hub of continuous celebration. In addition to hosting various domestic groups, Trump has broken with traditional U.S. electoral norms by openly welcoming foreign dignitaries and their representatives.

On the evening of Nov, 5, after his victory, Mar-a-Lago hosted people primarily from far-right factions, including foreign guests from Germany’s Alternative for Germany (AfD), the UK’s Reform UK and Eduardo Bolsonaro, the son of former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.

On Nov. 10, Israeli Minister for Strategic Affairs Ron Dermer visited Trump at Mar-a-Lago to deliver a message from Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu regarding Gaza, Lebanon and Iran.

U.S. President-elect Donald Trump shakes hands with Argentine President Javier Milei at the America First Policy Institute gala at Mar-A-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, US on Nov 14.

On Nov. 14, Argentina’s President Javier Milei spent a joyful evening at Mar-a-Lago, becoming the first foreign leader to meet Trump after his victory.

On Nov. 23, NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte met with Trump at the resort to exchange views on “global security challenges facing the transatlantic alliance.”

On Nov. 29, one day after Trump announced plans to impose additional tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had dinner with Trump at Mar-a-Lago. Trump later stated on Truth Social that the two had a “highly productive discussion” about fentanyl and the “massive trade deficit between the U.S. and Canada.”

As the threat of a potential trade war between the US and Canada looms, President-elect Donald Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau met up for a private dinner on Nov 29 evening at the Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida.

On Dec. 9, Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban met with Trump at Mar-a-Lago for the second time, having previously visited in July. The focus of their discussions was clearly the situation in Ukraine.

On Dec. 15, Akie Abe, widow of the former Japanese prime minister, Shinzo Abe, visited Mar-a-Lago to have dinner with Trump and his wife. Previously, the request of Japan’s Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba to visit Mar-a-Lago was politely declined by Trump’s team, citing “legal reasons.”

On Dec. 16, Masayoshi Son, president of Japan’s SoftBank, met with Trump at Mar-a-Lago. After their meeting, Son announced his commitment to invest $100 billion in the United States during Trump’s second term.

On the same day, Trump invited TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew to Mar-a-Lago for a meeting. This followed the rejection by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit of TikTok’s emergency motion and upholding an order requiring TikTok to divest its U.S. operations by Jan. 19. While TikTok says it will appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the outcome remains uncertain. Addressing the potential shutdown of TikTok in the U.S. will be one of the urgent tasks Trump must handle after returning to the Oval Office on Jan. 20. Trump didn’t hide his interest in TikTok’s algorithm when he told the media “I love TikTok.”

Trump was not merely waiting for foreign guests at Mar-a-Lago during his transition period. He also traveled abroad. On Dec. 7, he visited France to attend the reopening ceremony of Notre-Dame cathedral. The highlight of his visit was a three-way meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Elon Musk, who is widely regarded as the top contributor to Trump’s political campaign, has been a frequent presence at these events. He also had an extensive meeting with the Iranian representative to the United Nations in New York on Nov. 14. Recently, Musk has been energetically promoting Trump’s ambitious agenda, which includes annexing Canada and Greenland. It is increasingly evident that Musk, often humorously referred to as the “shadow president” by the U.S. media, will directly participate in foreign affairs once Trump assumes office.

These unorthodox diplomatic activities mark a significant departure from traditional U.S. political norms and send a message to observers keen to understand the characteristics and patterns of U.S. domestic and foreign policies over the next four years.

First, compared with his first term, Trump and his team will embrace a more “issue-driven” approach to governance, possibly even more so than before. Two major foreign policy priorities are likely to dominate: ending the war in Ukraine and imposing universal tariffs.

For Trump, these two issues are not merely campaign promises, but critical components for success in his second term. In Trump’s view, only a quick end to the Russia-Ukraine war will give Europe the motivation to reduce its reliance on the United States and take greater responsibility for its own defense. This would allow the U.S. to extricate itself from the crisis, restore budgetary stability and refocus on addressing the challenges posed by China’s rise.

Under the influence of figures like Robert Lighthizer, Trump strongly believes that the additional revenue from tariffs — paid by American importers — will offset the deficit caused by domestic tax cuts without triggering inflation. Consequently, the global question is not whether Trump will impose universal tariffs but rather how and to what extent.

Recently, The Washington Post reported that Trump’s economic and trade advisers are finalizing a list of global goods to be subject to tariffs — targeting all countries but focusing on critical imports. In response, Trump took to social media to accuse the news organization of spreading “fake news” and declare that his tariff policy “will not be scaled back.”

As a highly pro-Israel leader, Trump is expected to support Israel in expediting an end to the conflict there and push for a historic “big deal” between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. This would involve reviving the Abraham Accords, improving relations between Israel and the Arab world, exerting extreme pressure on Iran and seizing opportunities to instigate a color revolution within the country.

Second, Trump’s policies in his second-term will continue to be of a highly “transactional” nature — or, more bluntly, a form of blackmail. At a Mar-a-Lago dinner, he combined the issues of fentanyl, border control and tariffs with Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau. On Truth Social, he warned Europe to either buy massive quantities of U.S. natural gas and energy or face increased tariffs.

Similarly, Trump has raised provocative issues, including the ownership of Greenland and sovereignty over the Panama Canal, even suggesting making Canada the 51st U.S. state and renaming the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America.” These demands are largely financial, including lowering canal tolls for U.S. ships, improving Arctic shipping security in Greenland and securing compliance from Canada and Mexico on impending U.S. immigration, energy and tariff policies.

In this era of failing assumptions, who can rule out the possibility that some of Trump’s wild visions for expanding America’s frontier might partially or fully come true?

Trump’s coercion of close U.S. allies further reveals the great power chauvinism underlying American conservatism and right-wing factions. When a former world leader fixates on converting power into profits, and morphs into an outspoken and cynical extortionist, a loss of international respect is inevitable. But Trump and his followers care little about that. Their shortsighted focus on immediate gains and prioritization of narrow interests are propelling the U.S. into a realm of fantasy at high speed.

At the same time, America’s allies remain unprepared to disengage. Facing deepening security and development crises, they will cling more tightly to the U.S., even as the collective security framework of yesteryear erodes and gives way to unequal alliances requiring stiff fees and sovereignty concessions from the weaker countries. Yet such alliances might not last long, lacking cohesion and appeal.

Third, Trump’s second term is poised to pursue a greater expansion of conservatism globally. Leaders such as Hungary’s Orban, who describes his nation as a “conservative island in Europe’s liberal ocean,” and Argentina’s Javier Milei, who is pushing radical reforms, are key allies in this regard. They are elated to see a wave of conservatism sweeping across Europe, fueled by economic downturns, harsh living conditions, and relentless conflicts.

This movement has recently reached Canada, forcing leaders who have steadfastly championed liberal policies to either step down or lose their dominant positions. To Trump and his supporters, the time has come for a domestic conservative revolution to merge with a global conservative movement, with the ultimate goal of totally transforming the political landscape of the West.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is definitely in Trump’s mind. Trump’s ongoing fascination with Putin will likely result in early meetings focused on Ukraine and reshaping the geopolitical boundaries of Europe — or even the world. It is worth noting that there is an inexplicable affection for Putin among conservative Republicans, possibly resulting from their admiration for Leviathan and resonance with Russia’s self-perception of being the rightful heir to Europe.

The train of this century-long upheaval has already crossed the point of no return and is now accelerating downhill. The international order, founded on principles of sovereignty, institutional rules and multilateralism after World War II, faces an unprecedented survival crisis as it enters its 80th year. Europe has suddenly found itself adrift, a lone vessel in a vast, raging ocean, while even Asia, still relatively calm, is beginning to show signs of looming instability. With negotiations either underway or imminent between the United States and Russia — as well as within the Western bloc — on issues ranging from security to economics, one question looms: Will a new “Yalta system” emerge? Everyone needs to fasten their seat belts.

Trump’s bottom line, which he repeatedly emphasized during his campaign and transition period, is to “avoid a third world war.” His tendency to shift between issues, along with his increasingly entrenched behavioral patterns, suggests the adaptability of his policies. This also highlights that while the crises he sparks may be unpredictable, they are not necessarily uncontrollable.

Trump’s typical approach involves three steps: first, deliberately provoking controversy; second, applying maximum pressure to compel negotiations; and third, eagerly declaring victory, even if the concessions gained are minimal and disproportionate to his initial demands.

At the same time, some of Trump’s more radical ideas face resistance in Congress, not only from the Democrats, who are far from powerless, but also from the Republican establishment, which has proven more resilient than expected during the past several weeks. The future will largely depend on how effectively the U.S. political system can assert its influence.

Unlike eight years ago, when Trump’s primary base of operations during his first transition period was Trump Tower in Manhattan, no Chinese individuals have appeared on the guest list at Mar-a-Lago so far this time — at least not publicly.

This is not necessarily a regrettable situation, nor does it imply a lack of communication between the Chinese government and Trump’s team. Compared with eight years ago, China appears calm and composed, seemingly waiting for Trump’s team to finish their internal deliberations and clarify their China agenda, including specific demands such as tariffs. This time, China is notably better prepared, while Trump’s policy toolbox appears less full.

Trump himself seems aware of this, as evidenced by his unexpected remark to reporters on Dec. 16 after meeting Shou Zi Chew at Mar-a-Lago: “China and the United States could solve all the problems of the world.”

In recent years, the most critical bilateral relationship in the world has deteriorated rapidly as it has been reframed under the unilateral strategic competition narrative set by Washington. The scope for cooperation has narrowed significantly, and the trend toward decoupling has become more evident. Nevertheless, a certain level of restraint has been maintained, and direct military conflict has been avoided. Changes in America’s political landscape are likely to introduce a new agenda and a revised logical framework for decision-making. While no one harbors unrealistic expectations for a fundamental improvement in the relationship, it is also undeniable that a rebound after the steep decline is possible, even if only on a local level, influenced by internal and external factors.

Regardless of the specific actions Trump may take toward China after assuming office, one thing is clear: All policies enacted by both China and the United States toward each other will originate from their respective domestic priorities. For China, core national interests are non-negotiable, but strategic competition does not necessarily mean intense confrontation. The next chapter in Sino-U.S. relations presents both risks and opportunities, with the essence and boundaries of this relationship poised for redefinition.