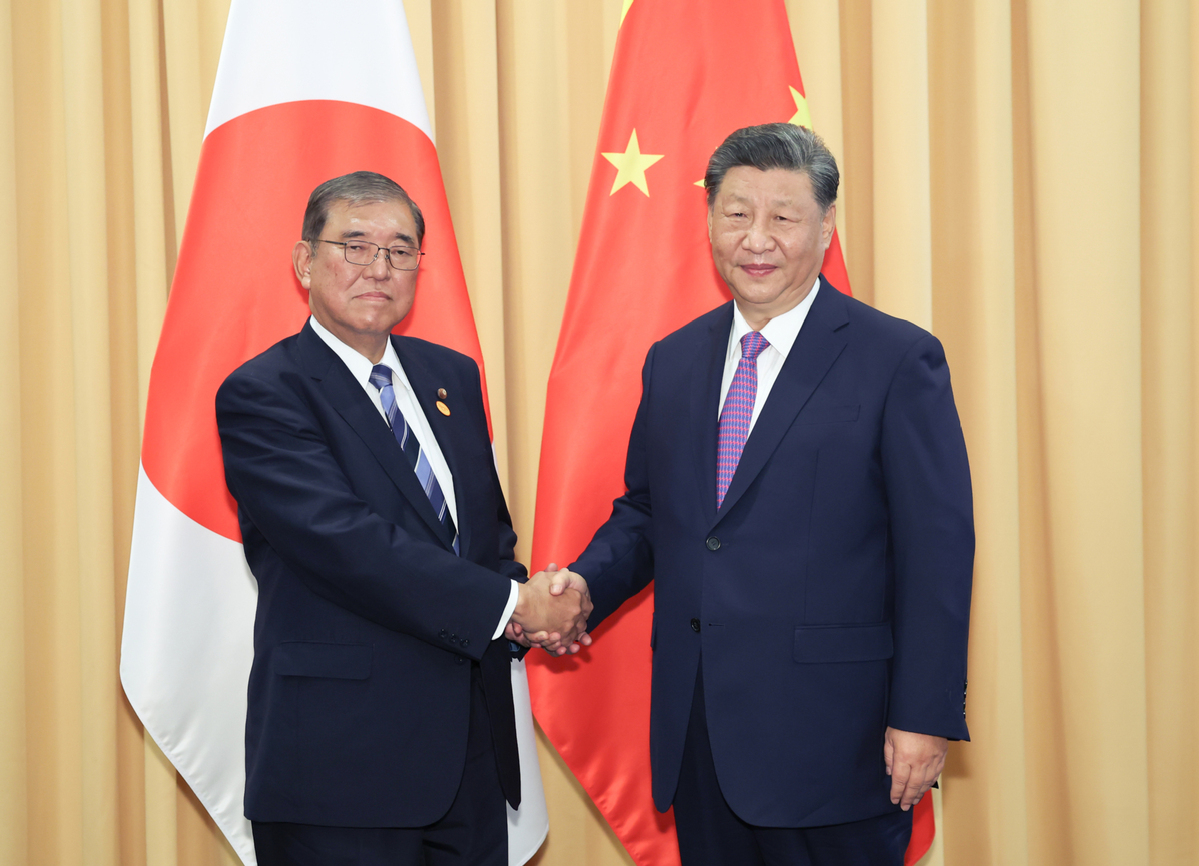

Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba on the sidelines of the 31st APEC Economic Leaders' Meeting in Lima, Peru on Nov 15, 2024.

On Sept. 27, Shigeru Ishiba was elected president of the Liberal Democratic Party; then, on Oct. 1, he officially took office as Japan’s new prime minister. A longtime conservative politician deeply involved in Japan’s defense policy, Ishiba proposed several major initiatives during his campaign, including the establishment of an “Asian NATO,” revisions to the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, and discussions about the potential deployment of nuclear weapons in Japan. Does the advent of the Ishiba Era signify a significant shift in Japan’s strategic direction? What implications does this hold for China-U.S.-Japan relations and regional security?

From a strategic standpoint, Ishiba’s vision for a new era in Japanese security policy is focused on gaining strategic autonomy from the United States. This direction shows strong continuity with the policies of the preceding Abe and Kishida administrations. Whether through Abe’s lifting of restrictions on collective self-defense or Kishida’s formulation of three key security documents, the underlying theme has been Japan’s postwar conservative political forces striving to reduce dependency on the U.S.

Ultimately, this political trajectory aims to revise Japan’s constitution, a mission established as a core task since the founding of the LDP in 1955. From Shinzo Abe’s notion of escaping the postwar regime to Shigeru Ishiba’s so-called postwar political settlement, a clear lineage emerges, making Japan’s political evolution increasingly transparent.

For both China and the United States, responding to a Japan that increasingly seeks and practices strategic autonomy presents a significant strategic challenge.

On a tactical level, Ishiba stands out by explicitly advocating ideas about the “relative decline” of U.S. power and doubts regarding U.S. security guarantees. These notions underpin his vision for a new, more equitable Japan-U.S. alliance. Ishiba argues that the existing logic of the alliance — wherein the U.S. protects Japan while Japan hosts U.S. military bases — requires reform. He introduced the concept of “mutual security obligations,” suggesting that Japan should also offer security guarantees to the U.S. While not a new idea, Ishiba specifically proposes stationing Japan’s Self-Defense Force on Guam and utilizing U.S. bases for training, aiming to elevate the Japan-U.S. alliance to be equivalent to the U.S. alliance with the United Kingdom. He also promotes strengthening smaller multilateral alliances to embrace South Korea, the Philippines, India and Australia, thereby continuing the policies of his predecessors.

However, Ishiba’s clear push for an Asian NATO represents a new development that aims to establish a dual-axis security framework in East Asia, particularly at sea. On nuclear issues, while Abe called for discussions on NATO-style nuclear sharing, Ishiba explicitly mentioned the possibility of allowing the U.S. nuclear weapons to enter Japan, signaling a partial revision of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles.

For the U.S., the key question is whether Ishiba will emerge as a De Gaulle-like leader, steering Japan further along the path of strategic autonomy, or as a leader more like Churchill. This distinction will be crucial for the U.S. as it navigates the Ishiba era and manages its alliance with Japan. Internal divisions within the United States suggest a relative weakening of the country’s ability to engage effectively in international affairs, potentially requiring Japan to assume greater responsibility in upholding the U.S.-led order in Asia. However, an overly autonomous Japan could provoke regional anxiety and lead to scenarios where the U.S. becomes entangled in conflicts it cannot control. The Biden administration’s goal of integrated deterrence in the Indo-Pacific seeks to forge an alliance that fully leverages Japan’s strengths while maintaining oversight.

The concept of an Asian NATO has historical precedent: After World War II, the U.S. attempted to establish the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, a NATO-like entity in Asia, which ultimately failed. Reviving this idea could lead to a confrontation between China and the U.S. in the region, raising concerns among ASEAN members and others. The evolving U.S.-Japan relationship will likely continue to be shaped by political dynamics, particularly now as the U.S. prepares for its next presidential election.

For China, the rise of a more strategically autonomous Japan presents both challenges and opportunities. Ishiba argues that the absence of a collective defense mechanism in Asia makes the region vulnerable to conflict. He asserts that establishing an Asian NATO is essential to deter China. If this logic translates into policy, it would undoubtedly have severe repercussions for Sino-Japanese relations.

However, history shows that collective defense systems in East Asia have struggled to succeed. Overemphasizing the mutual defense obligations of Japan and the U.S. could also lead to public fears in Japan about being drawn into U.S. military conflicts. Both the LDP and opposition parties have expressed concerns over Ishiba’s bold proposals, particularly as they have not been fully coordinated with the United States. A cautionary tale is that of former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, who, upon taking office, proposed relocating the U.S. military base from Okinawa, which led to strained U.S.-Japan relations and his eventual resignation. Conversely, while Ishiba emphasizes the deterrent power of the U.S.-Japan alliance and multiple small multilateral alliances, he also advocates building mutual trust — particularly highlighting the importance of direct communication between Chinese and Japanese leaders.

As Japan enters the Ishiba era, China-U.S.-Japan relations are poised for another round of adjustments. Last year, the leaders of China and Japan met in San Francisco, reaffirming their commitment to a strategic and mutually beneficial relationship. Recently, they reached a consensus regarding Japan’s handling of wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear plant. Building a stable, constructive and era-appropriate Sino-Japanese relationship reflects the mainstream views of both nations and requires a foundation of positive, rational understanding. Beyond official channels, there is an urgent need to expand and strengthen social interactions, including Track II and Track 1.5 diplomacy, to engage intellectuals and scholars.