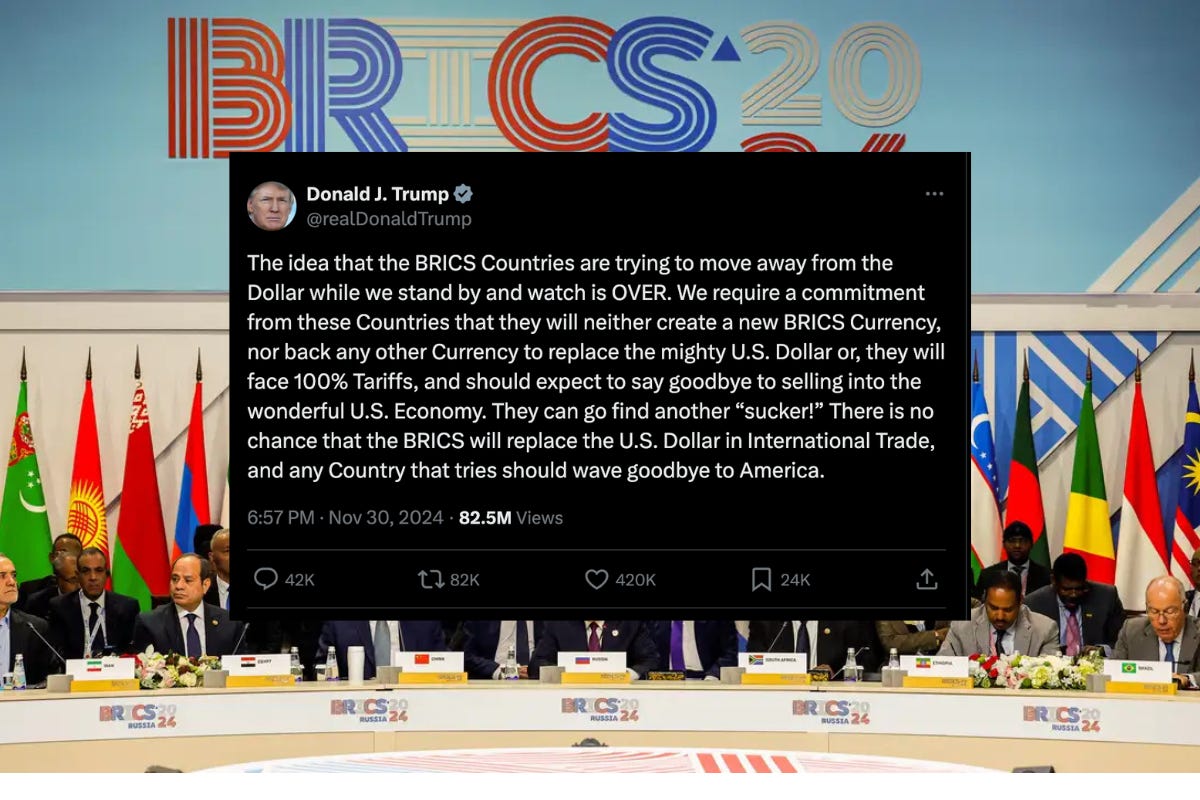

In a social media post on January 30, 2025, US President Donald Trump threatened 100% tariffs on BRICs countries unless they committed to “neither create a new BRICS Currency, nor back any other Currency to replace the mighty US Dollar”, and if they did not they “should expect to say goodbye to selling into the wonderful US economy”.

This is neither speaking softly nor, in fact, yielding a big stick. Trump speaks loudly but the stick isn’t as big as it once might have been.

Indeed, rather than act to preserve US dollar primacy, moves to impose tariffs on BRICS could potentially - indeed, in all likelihood - hasten the expansion of currency multipolarity with adverse effects on the American political economy and living standards. On this score, while any changes to key system parameters are by nature disruptive, the issue isn’t whether change is implied (that’s a given) but what the likely trajectory of the changes are and their likely impacts on different stakeholders and ultimately, on the system at large.

Today, the US makes up about 15% of global trade, and about 16.5% of China’s trade. This has been declining, as world trade continues to expand. In 2018, the US made up about 20% of global trade. Put plainly, it isn’t as important today as it once was, and threats of loss of US market access simply don’t have the same system-wide effects as they once would have had.

Trade between the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, United Arab Emirates, and Indonesia) and the US for 2022-23 is estimated to have been ~US$1.05 trillion, with the U.S. running a $424.5 billion trade deficit. Of BRICS’ exports to the US, exports from China account for about 73%. Of BRICS’ aggregate surplus vis-a-vis the US, some 84% is due to China’s trade surplus. Trade between the US and Russia and Iran are already negligible, due to existing sanctions. Put plainly, the issue with BRICS is largely a US-China question, which means that most other BRICS nations are unlikely to be particularly perturbed by threats of tariffs, though the question remains the extent to which they can adjust to any loss of US markets.

Let’s assume that Trump does proceed with imposing 100% tariffs on all BRICS exports to the US. Assume too that BRICS nations will retaliate, with the result being a 90% reduction in trade volumes between these nations. In other words, Trump’s tariffs plan will put an end, for all intents and purposes, to trade between BRICS and the US.

What are the potential flow-on implications and effects?

Firstly, BRICS nations will need to adjust to the loss of the US market. This is Trump’s ostensible ‘big stick’. The potential for market substitution and for general global growth to absorb loss of US markets will vary from country to country. That said, it is likely that for the most part, all BRICS nations will adjust within 3-5 years. Chinese exports can be expected to adjust within 3 years, according to modelling undertaken by Simon Evernett. As they adjust, and desist from trading with the US, the functional need for US dollar settlements diminishes. China in any case isn’t as export dependent as many believe.

If Trump’s aim of the BRICS tariffs is to build a bulwark against dedollarisation, the move runs the risk of backfiring. In this context, recall that BRICS’ full members represent around 55% of the world’s population and 45% of global GDP (in nominal terms). For a group of economies and populations of such scale to effectively be compelled to decouple from trading with the US will have substantial implications for the US dollar hegemony.

Secondly, the US itself will need to adjust from loss of markets and loss of supplies. Like BRICS nations, the adjustment is likely to be variable across the complex US economic system. It is reasonable to assume that the US will also adjust for many standard items within 3-5 years, but for some categories of upstream inputs, capital equipment and even some finished goods, it could take up to a decade to find alternatives. Some of this adjustment will simply see Chinese firms expand into non-tariff impacted countries, while the US will also be driven to increase imports from Germany, Republic of Korea and Japan for capital equipment, machinery and electronics.

Thirdly, core inflation in the US could be impacted by 3-6%. The poorest in the US community will be hardest hit. Retirees and fixed income earners will also be hit by rising healthcare, drugs and utilities costs. Income inequality will worsen. Those promised that the American Dream will be restored are likely to be disappointed, again.

Fourth, in the face of rising inflation, the Fed will be tempted to increase interest rates, right or wrong. The effect will be distributional. Those holding interest-bearing assets will see income growth; those holding interest-bearing liabilities will face further pressure on constrained budgets. Cost of capital for investment will increase.

Globally, demand for US dollars is likely to reduce, because of reduced need for USD for trade settlements. This has flow-on implications for US credit rating, living standards and ultimately US dollar-driven political and economy power.

As for the ambitions of tariffs catalysing the rejuvenation of American manufacturing, there are likely to be considerable barriers to the realisation of this hope. For starters, the US would need to dramatically increase imports of capital goods, robotics, machinery and other equipment if it is to enable the expansion of domestic manufacturing output. Having imposed tariffs on BRICS countries, the US is likely to have to import these goods from Germany and Japan, in the main. In effect, the US shifts its trade deficits around without necessarily fundamentally changing the productive structure of its domestic economy in the short term.

Additionally, modern manufacturing is not only capital intensive it also demands a workforce that is highly educated. A numerate and literate workforce is a condition precedent of a viable manufacturing ecosystem. In this environment, the US would firstly need to overcome low relative literacy and numeracy rates in its population or rely on highly skilled migrants. In the short term, a political culture that has lambasted an educated elite in favour of promoting pride in ignorance in the name of “common sense”, may win votes but doesn’t support industrial rejuvenation.

Lastly, a political economy that is heavily tilted in favour of the financialised sectors of finance, real estate, insurance and the like has been a cause of industrial decline for over 5 decades. Without addressing this structural feature, access to and ability to mobilise the necessary money capital - be it in equity or debt form - to expand manufacturing will be extremely challenging.

Meanwhile, the global system in which the US has exchanged IOUs for real economic resources is becoming less and less appealing to those with the resources, the knowhow and the technologies to transform them. This is even more the case when these IOUs are increasingly weaponised. The threat of tariffs is doubtless disruptive, but there is a real possibility that they will hasten the demise of US dollar hegemony and consolidate the evolution towards a multipolar trading environment.

Rather than be cowed by the threat of tariffs, BRICS may well embrace the need spurred on by them to drive home the new models of collaboration that are already in place and lock down the BRICS Clear project to mitigate future risk of dollar weaponisation.