On October 18, 2018, the European Union (EU) will present its connectivity strategy for Eurasia to Asian partners at the 12th Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) in Brussels. The document, issued in September, provides a comprehensive response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with serious implications for China-U.S. relations.

The strategy states clearly that Europe wants to collaborate with Beijing in addressing infrastructure needs in the Euro-Asian area. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has estimated that Asia faces a need for $26 trillion worth of infrastructure investment until 2030. In this context, Europe welcomes China’s connectivity initiative, though it would like BRI projects to comply with the financial, environmental, social, and labor standards promoted by the West. At the same time, the upcoming EU document makes clear that Brussels is ready to cooperate with the U.S. in containing those elements of China’s BRI – such as the opaque financial deals and tendering processes - which are not in line with Western-defined principles and standards.

Thus, expect Europe’s connectivity strategy to be used by both Beijing and Washington in their tussle for global primacy, with both parties framing Europe’s declaration as codified support for their policies.

Europe’s Connectivity Concept

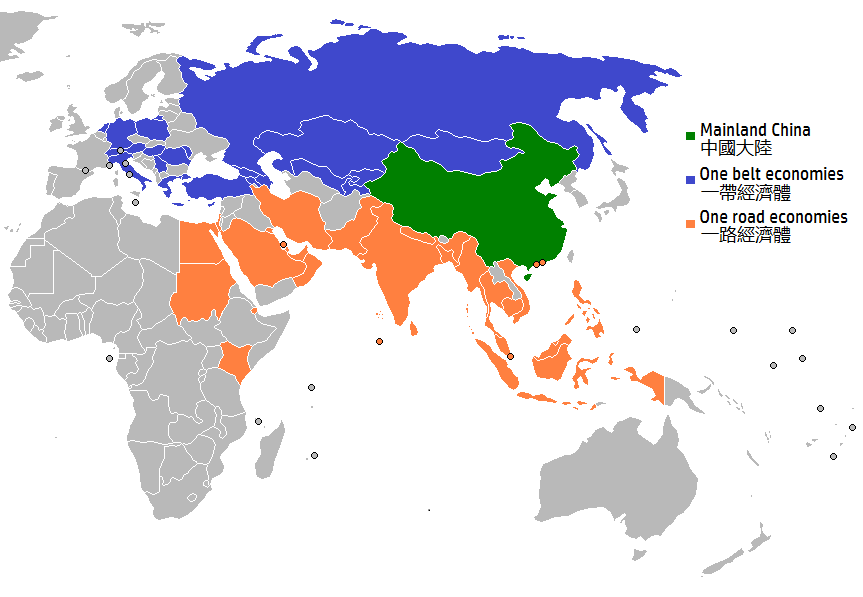

Since the early 2000s, the EU has been promoting various initiatives to improve connectivity among EU member states as well as in the neighboring countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The launch of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in late 2013 accelerated this process to include the whole Eurasian continent.

Since the beginning, Europeans have observed the development of China’s connectivity initiative with great interest – unlike the U.S., which opposed it from the start. For instance, all EU member states have joined the China-led Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Many projects supported by the AIIB are co-financed with the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Meanwhile, Washington remains an outsider to these developments.

In the 2016 Global Strategy on the EU’s Foreign and Security Policy, Brussels committed itself to strengthening Europe’s relations with a “connected Asia” and called for the EU to pursue a “coherent approach” to connectivity. In this context, the European External Action Service (EEAS, which functions as Europe’s diplomatic corps) and the European Commission carried out a mapping exercise of Euro-Asian connectivity last year, involving EU member states, EU delegations working in countries in Europe and Asia, and various European business associations, think tanks, academics, NGOs and experts. This exercise reviewed existing policies and projects and was discussed with the EU’s main partners, including China, India, Japan, the United States, Russia and ASEAN. The main findings were issued in the November 2017 ‘Euro-Asian Connectivity Mapping Exercise - Main Findings’ which forms the basis of the Euro-Asian Connectivity Strategy.

The strategy focuses on all modes of transport links – land, sea and air – as well as digital and energy links in the Euro-Asian area. It seeks to promote a shared concept of connectivity which respects labor, social, and environmental standards and follows the principles of sustainability, transparency, market principles, open procurement rules, and equal treatment and equal access. These are values and principles which, according to the Europeans, are not always upheld by Chinese companies operating in the BRI project countries.

Challenging the Chinese Silk Roads

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is increasingly being viewed with scepticism in many European capitals, including Brussels. In April 2018, the German business newspaper Handelsblatt revealed that 27 of 28 ambassadors from the EU in Beijing compiled a report accusing the BRI of limiting free trade and providing subsidized Chinese companies with unfair advantages. The Ambassador of Hungary in Beijing was the only European diplomat to refuse to sign the document.

There are growing concerns in Europe that through the Belt and Road Initiative, China seeks to tackle industrial overcapacity at home by “dumping” goods priced below production costs, a strategy that could bring industrial lines across Europe to their knees. Moreover, EU policymakers fear that Beijing wants to revise the global rules on commerce and investment. They also express concern that BRI projects could be used to exert influence over EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe, which seek to attract Chinese loans and investment to bolster their economies.

European critics also worry that the Chinese initiative lacks transparency and that the opaque financing deals may threaten the competitiveness of European companies. It is increasingly evident that Chinese companies are awarded the contracts with little respect for open procurement rules. China usually requires that infrastructure works financed by its soft loans be carried out, mainly, by Chinese companies, as is the case with the high-speed rail link between Belgrade and Budapest – something that has attracted criticism from the EU.

Europe is not alone in seeking to counter what many in Brussels perceive as the negative aspects of China’s BRI. Washington is moving in the same direction.

Towards Transatlantic Entente

During his visit to Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia in early August, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo laid out the Trump administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy, announcing that the U.S. would invest $113 million in sectors such as technology, energy, and infrastructure. Washington’s approach, like Brussels’, seems to prioritize private-sector investment, which contrasts with China’s state-led Belt and Road Initiative.

Consultations between the transatlantic allies on how to respond to China’s BRI have increased recently, particularly in light of developments in South and Southeast Asia. For instance, Pakistan now wants to renegotiate agreements related to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), signed under China’s BRI, for fear that it could become a ‘debt trap’ for the country. Further, Malaysia has cancelled a pipeline project linked to China’s BRI and suspended other BRI projects as the investments in some of the projects link the government to the scandal-plagued 1Malaysia Development Berhad (MDB) investment fund. The suspended initiatives were estimated to be worth nearly $20 billion.

EU and U.S. policymakers worry that China is encouraging indebtedness in various countries in order to gain control of strategic assets when debtors default on repayments, sometimes referred to as creating “debt traps,” although Beijing denies this. Western media recently reported that Sri Lanka was forced to surrender a 99-year lease on a strategic port to a Chinese conglomerate after the port (financed with loans from Beijing) failed to generate significant income. As a result, the U.S. is now considering creating an agency called the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation that could invest up to $60 billion to counter what some in Washington view as China’s use of ‘debt-trap’ projects to gain influence abroad.

The EU’s connectivity strategy is likely to be welcomed in Washington, as it provides the Trump administration with additional ammunition in its tug-of-war with Beijing. The document contains critical views of China’s BRI which are in line with U.S. perspectives on the initiative. The connectivity strategy is mainly aimed at addressing infrastructure needs in Eurasia, but it will inevitably be caught up in the long-term great power rivalry between China and the U.S.