A year ago, China’s 1st quarter plunge was -6.8 percent, due to the pandemic effect. In the West, it was widely seen as the “end of China's growth story.”

But in February 2020, I predicted a turnaround in the increase of new virus cases in China, with the beginning of the economic rebound in the 2nd quarter. While such contrarian projections were widely rejected in the West, both predictions proved valid.

China's rebound turned out to be even stronger. Following the 6.5 percent expansion in the 4th quarter of 2020, China’s GDP rose to a record 18.3 percent year-on-year in the 1st quarter of the ongoing year. Though benefiting from the base effect, due to the pandemic plunge a year ago, the performance reflects strong impetus for normalization.

Indeed, China’s economy continues to boom in April, with strong exports and rising business confidence supporting the recovery.

Expansive and broad momentum

The strategic rebound effort began with supply-side expansion. It is now broadening, thanks to improving domestic demand and higher exports. All major indicators are already above the pre-crisis level. The Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) has grown 13 months in a row. With the turnaround in consumption, even the services PMI has been expanding almost a year.

With the easing of social distancing, retail sales, which have been expanding for 8 months, are likely to strengthen. Due to lingering pandemic waves in many parts of the world, international travel restrictions will foster domestic spending in China.

After the historical pandemic-induced economic plunge, the international auto sector is recovering with U.S. retail sales at 26 percent in the 1st quarter. However, China’s auto production has increased for 12 months at over 40 percent year-on-year.

Last year, China’s macroeconomic performance relied on fiscal and monetary support, while a surge of debt sparked unease among some observers. With recovery, government authorities have urged banks to shun disproportionate lending growth. Yet, concerns over monetary tightening seem exaggerated.

In line with its normalization objectives, China’s central bank seeks to cool credit growth to preempt debt and financial risks. It is moving cautiously not to disrupt the recovery. And inflation has been in positive territory since March.

Most importantly perhaps, China’s financial integration with the global markets is supporting its domestic momentum.

Government bonds attract global portfolios, innovation FDI

In particular, Chinese government bonds (CGBs) are growing in popularity across global fixed income portfolios. In just two years, foreign holdings of CGBs have nearly doubled to almost $310 billion.

Despite the U.S. government’s efforts at China’s geopolitical containment, American investors seek steadiness and diversification through CGBs’ high and stable yield. It’s a numbers game: Chinese 10-year bonds have yields over 3.2%, while the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield is at 1.7%.

And make no mistake: This is just a prelude. Over the next 20 months, more than 360 onshore Chinese bonds will be added to major investment indexes tracked by global investors. Reportedly, the full inclusion will attract around $150 billion of foreign inflows into China’s $13 trillion bond market; the third-largest in the world after the U.S. and Japan.

Furthermore, with increasing investment by both private and state-owned enterprises, public investment will rise faster, thanks to the push under the 14th Five Year Plan. Gradually, that investment will shift from manufacturing and real estate, which fueled China’s old growth model, toward R&D, as the new growth model takes hold. The latter is accelerating, thanks to the rapid expansion of China’s Silicon Valley in the Greater Bay Area across Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao.

As China has begun the transition to higher value-added, parts of the cost-focused supply-chains in the Chinese mainland are relocating to Southeast Asia. That's likely to boost regional integration under the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which is a market-led regional win-win for economic development – despite ongoing external geopolitical win-lose attempts to split Asia.

In the (dark) footprints of Smoot-Hawley

Currently, the Biden administration has an “everything doctrine,” as Jeremy Schapiro of the European Council for Foreign Affairs has observed. The White House is offering nostalgic lofty goals, presumably to “make America great again,” once again. However, the key international uncertainty is whether the U.S. will put global interdependency ahead of assertive geopolitics. The implications will reverberate worldwide.

As long as the Biden-Blinken trade stance seems like a replica of the Trump-Pompeo tariff war, neither U.S. recovery nor global positive prospects are likely to prove sustained. The trade war will undermine both. In the 1930s the Smoot-Hawley Act was enacted to boost U.S. jobs and international competitiveness. In practice, it caused a series of counter-retaliations in trade, contributed to the Great Depression, and paved the way to World War II. Today, the relative magnitudes are not that different. But the stakes are far higher and global.

The quest to hold on to the Trump-Pompeo legacies is likely to cause new economic instability and geopolitical tensions that have potential to derail the Biden administration’s own domestic programs, which rely on huge debt-taking, multi-trillion-dollar stimulus packages, and continued monetary easing. Or what economist Paul Krugman has called “super-core inflation amid a year of bottlenecks and blips.”

Global economic recovery or geopolitical stagnation

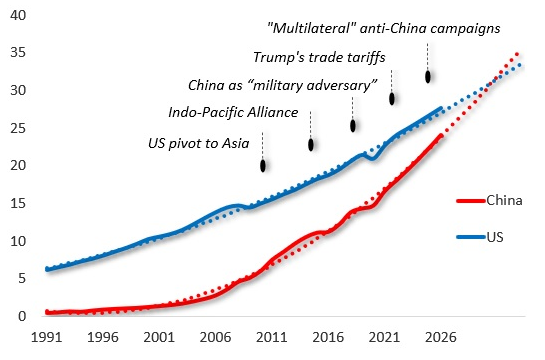

In the early 2010s, when the Obama administration initiated the geopolitical pivot to Asia, it launched the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Indo-Pacific alliance, with the former excluding China and the latter seeking to contain its rise. The Trump administration built on these policy mistakes by defining China as a “military adversary,” and starting the misguided tariff wars.

The Biden administration seems intent to replicate past mistakes with efforts to “multilateralize” Trump’s anti-China campaigns. The protectionist instinct, as Adam Posen, the president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) recently warned, is accompanied by “America’s self-defeating retreat.”

The ultimate objective seems to destabilize China’s economy so that its size would not surpass that of the United States in the next few years (Figure).

Figure China’s Economic Rise, U.S. Geopolitical Responses

Yet, the reality is that, with progressive normalization and relative international stability, China’s expansion momentum will steady toward the end of the year. The strong rebound will allow it to exceed the 2021 growth target of “above 6 percent.” Even with moderation, growth is likely to exceed 6.5 percent and has potential up to 8.5 to 9.5 percent in 2021, with likely deceleration to 6 percent in 2022.

Last December, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) forecast that China will account for over a third of world economic expansion in 2021. However, just as Trump’s trade war in 2018 derailed the nascent global recovery, any effort to undermine China’s economic growth will penalize not just China, but U.S. recovery and the global economic prospects.