During U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s second visit to China in April, both countries emphasized areas of shared interest, such as avoiding decoupling and responding to financial risks. Yellen expressed concern about China’s “overcapacity” in emerging fields. Since the United States launched a trade war with China in December 2018, economic and trade relations between the two nations have faced significant challenges in the past six years.

A review of developments in this period reveals that Washington has pursued three strategic goals in its economic and trade relations with China and that its approach has evolved through three distinct stages. Their economic relations have major implications not only for the two nations but also for global trade and industrial structures. Theories of “overcapacity” and “debt traps” are expected to be two major narratives deployed by Western countries to undermine China’s industrial and economic development and trade ties.

On the surface, the China-U.S. trade war appears to be about trade imbalances. In essence, it is driven by U.S. anxiety over China's rapid ascent in the global industrial structure and its concerns about China’s dominance in certain segments of the global supply chain. Since the Trump administration, Washington has tried to exclude China from critical areas of the global supply chain and hinder its progress toward a technology-intensive industrial structure. The U.S. government’s decoupling and de-risking strategy targets labor-intensive industries in China, aiming to apply business and technological pressures to hold back China’s economic development at its source. Because of the potential loss of tax revenue and profits caused by the exodus of labor-intensive sectors, the Chinese government and businesses, the U.S. believes, would be hesitant to invest in emerging technology-intensive industries. The previous and current administrations in the United States have implemented specific measures to this end.

Regarding labor-intensive industries, the Trump administration imposed high tariffs on up to $200 billion of Chinese imports, and adopted stigmatizing tactics. For example, it claimed that the production of certain Chinese goods was tied to “forced labor.” This was to pressure multinational companies to stop sourcing parts and components and end products from China. The Biden administration has maintained its predecessor’s tariffs and has continued to play the human rights card. Additionally, it has accelerated offshore outsourcing and friendsourcing, and adopted multiple means to compel multinational companies, including some from China, to relocate their industrial chains outside of China.

In capital-intensive industries, both administrations have intertwined economic issues with security concerns. In the name of de-risking, they have pressured European countries to withdraw their business operations from China and banned Chinese capital-intensive products from entering the U.S. and European markets, thus restricting their access to the global market. Victims of this approach include telecom equipment, digital infrastructure and new-energy vehicles produced in China. For example, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) recently unveiled a new proposal aiming to permanently prohibit Huawei, ZTE and other Chinese telecom equipment manufacturers from certifying wireless equipment, effectively barring their products from the U.S. market.

In China, technology-intensive industries, led by semiconductors and artificial intelligence, are still in their infancy. By partnering with countries that dominate these sectors, the Biden administration has formed tech alliances to impose a technological blockade on China. At the same time, it has curbed investment by domestic venture capital and private equity funds in some Chinese high-tech companies. The administration is attempting to prevent China from climbing up the global tech ladder by targeting three fronts: capital, technology, and market access.

Since the Trump administration started the trade war in December 2018, Washington’s economic and trade policies toward China have evolved through three stages. Initially, the goal was to decouple and promote the reshoring of industries. Next, a “small yard, high fence” approach was adopted to prevent industrial upgrading in China. Currently, the focus is on defending the domestic manufacturing industry at all costs.

Upon taking office, the Trump administration imposed tariffs on goods from many countries and regions, including China, to fulfill its campaign slogan “Buy American, hire American.” The ultimate goal was to reverse trade imbalances and promote the reshoring of manufacturing activities. Based on the value and structure of bilateral trade and the geographic location of its trading partners, the administration calculated the extent of U.S. losses from international trade and then imposed different levels of tariffs on different countries. Given its long-standing trade deficit with China, it imposed the highest tariffs on Chinese goods. This approach not only worsened China-U.S. relations but also strained economic relations with Canada, Mexico and many traditional U.S. allies in Europe.

As the administration suppressed Chinese high-tech companies, it has tried to bring labor-intensive manufacturing back to the United States through tariffs and decoupling.

The Chinese government navigated the situation with patience and composure. In addition to imposing reciprocal tariffs, China relied on the global market to accelerate the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative. For example, following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for medical supplies and daily necessities surged around the world. Thanks to its unparalleled manufacturing capabilities, China resolved the trade conflicts created by the Trump administration and undermined Washington’s attempt to decouple from China and promote industrial reshoring.

When President Joe Biden took office, he faced high inflation at home and realized that it was difficult to bring labor-intensive industries back in the short term. In addition, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine caused chaos in the energy market across Europe and triggered a restructuring of the global manufacturing sector. In response, the Biden administrate has adjusted its economic and trade policy toward China, shifting the focus from bringing manufacturing jobs back to preventing China from advancing in high-tech fields, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence and biopharmaceuticals.

The Biden administration swiftly formulated a new national security strategy, seeing Russia as a short-term security threat and China as a long-term competitor. It repaired rifts in relations with allies caused by its predecessor and, more important, formed technology alliances, such as CHIP 4, to curb China's industrial advancement. At present, it has prohibited TSMC from manufacturing chips for Huawei and banned companies in the Netherlands and Japan from exporting chip-making equipment to China, including photolithography machines and photoresists.

Meanwhile, Congress approved the CHIPS and Science Act to subsidize domestic semiconductor companies and compelled TSMC and Samsung to build chip foundries in the United States. While continuing the Trump administration’s tariffs on Chinese goods, the U.S. has intensified its efforts in offshoring and friendsourcing for the purpose of bringing labor-intensive industries back to the United States (or at least moving them out of China).

In response, the Chinese government has adjusted its industrial strategy. Specifically, it has

• devoted more resources to indigenous innovation systems for the sake of an independent and controllable industrial chain;

• increased investment in the R&D of emerging technologies;

• accelerated the development of new infrastructure, such as 5G telecom networks and smart grids; and

• bolstered the development of new industrial clusters for new-energy vehicles, large aircraft and biopharmaceuticals.

Huawei’s recent launch of new models of mobile phones, such as the Mate 60 Pro, signifies its breakthrough in overcoming the U.S. technological blockade on advanced chips. Leveraging China’s ultra-large domestic market, Huawei mobile phones have surpassed Apple to reclaim the top spot in the domestic smartphone market.

According to a report by the South China Morning Post, China’s chip production in the first quarter of 2024 surged by 40 percent and chips made at home dominated the domestic market. These facts prove that the Biden administration’s “small yard, high fence” strategy has failed to hinder China’s ascent on the global tech ladder.

As noted earlier, neither the Trump administration’s decoupling strategy nor the Biden administration’s “small yard, high fence” approach have achieved their intended goals of reshoring manufacturing jobs and curbing the advancement of Chinese industries.

At present, China and the United States are engaged in intense competition in the artificial intelligence sector. The United States maintains absolute R&D advantages in terms of computing power, algorithms and data, but these strengths haven’t translated into clear industrial advantages. At the same time, Chinese products from emerging industries — notably the “new trio” of new-energy vehicles, photovoltaics and batteries — are gradually rising to dominate the global market, with the country rapidly closing the gap with top performers in artificial intelligence.

These developments have heightened the anxiety of the United States. From U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo’s calls to suppress China’s high-tech sector to Treasury Secretary Yellen’s allegation of China’s “overcapacity,” the United States is employing various tactics to thwart China’s progress in the AI field. Moreover, it has imposed strict restrictions to prevent the new trio from entering its market, aiming to protect its domestic auto industry. On May 3, for example, the U.S. government released final rules on the clean vehicle provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, stating that electric vehicles made with Chinese materials will be ineligible for tax credits.

We are currently in the early stage of the third phase. In managing its trade relations with China, the current U.S. administration’s top priority is to mitigate the impact of China's emerging industries, particularly new-energy vehicles, and to protect the domestic manufacturing industry. Given that the automobile industry is at the heart of the manufacturing system in the Western world, Washington is likely to join forces with major Western automakers to curb the rapid global expansion of Chin’s new-energy vehicles, meaning that China’s emerging industries could encounter mounting challenges ahead.

It is foreseeable that Western media outlets, academic communities and government agencies will go all out to hype the perceived threats posed by China’s alleged overcapacity and global dumping, claiming that the country is exporting excess production capacity to Western countries and ensnaring developing countries in a debt trap. “Overcapacity” and “debt trap” have become the two narratives employed by Western countries to impede China’s industrial advancement and the implementation of its Belt and Road Initiative.

China-U.S. economic and trade relations have experienced mounting difficulties since 2018. The goals set by the previous and current administrations in the United States have not been achieved, but this does not mean that Washington will abandon its established strategy, nor does it suggest that China is in a superior position. The two nations now find themselves in an unprecedented stalemate in their economic and trade relations, industrial development and high-tech competition. It is imperative for them to find new areas of cooperation on the basis of fair and open competition, to guard against common risks and to prevent global fragmentation in the science and technology industry and market.

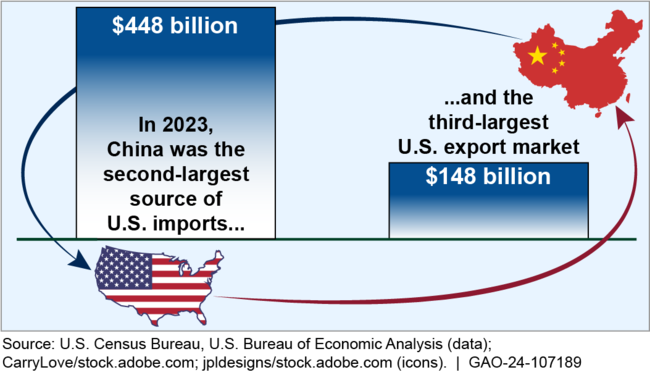

According to “U.S. Exports to China 2024,” a report published by the U.S.-China Business Council in April, exports of semiconductors and their components to China have dropped, but China remains the third-largest export market for U.S. goods. The Chinese market supports numerous U.S. jobs, particularly in agriculture and services. The two nations have broader space and potential for cooperation in emerging industries. Exemplified by the rapid development of Tesla in China, their close partnership in new-energy vehicles has profoundly changed the pattern of global manufacturing, especially in the automotive sector.

The current state of bilateral relations in agriculture, services and NEVs underscores the fact that engagement and cooperation underpinned by self-confidence and mutual trust are essential prerequisites for a more promising future in China-U.S. relations.