Section I: Conceptual Narrative 1 — The Thucydides Trap

The Thucydides trap is a term coined by Graham Allison in 2012 to capture the idea that the rivalry between an established power and a rising one often ends in war. Last year saw much public discussion of this idea because of the surge in U.S.-China tensions that followed President Donald Trump’s decision to impose tariffs on almost half of China’s exports to the U.S.

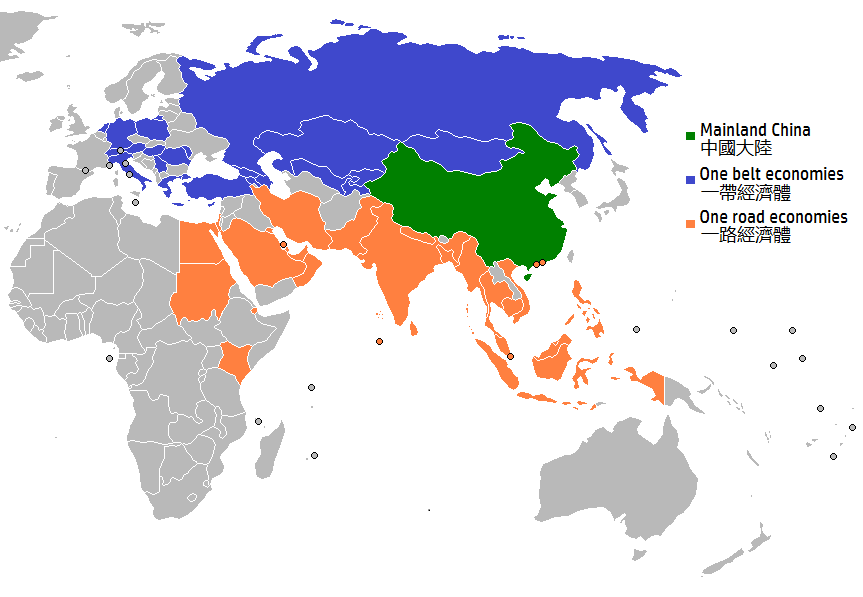

However, some American policymakers argue that the real source of tension are the assertive policies pursued by Xi’s China, including the creation of military bases on artificial islands in the South China Sea. From this great power competition perspective, China’s BRI is a major part of Xi’s aggressive challenge to the dominant global position held by the U.S. The initiative is especially significant given that it marked a significant turning point in China’s foreign policy stance.

Allison’s Thucydides trap has influenced state officials from both China and the U.S. For example, in 2013, Xi told a group of Western visitors that “[w]e must all work together to avoid the Thucydides trap.” On the American side, the U.S. Defense Department’s 2018 report on China’s military power warns that the BRI “is intended to develop strong economic ties with other countries, shape their interests to align with China’s, and deter confrontation or criticism of China’s approach to sensitive issues.” These developments suggest that Allison’s narrative has already shaped the statecraft of officials from China and the U.S.

What is the rationale behind this conceptual narrative of the Thucydides trap? Perhaps, it is the fear of the unknown. A rising power always possesses something unfamiliar to the reigning power. Having become accustomed to being a hegemonic presence, the reigning power has a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. As the rising power disrupts the status quo, adopting a policy of containment appears to be the reigning power’s rational response. Facing an aggressive stance from the reigning power, the rising power is incentivized to protect its newly gained influence on the global stage. This behavior is likely to prompt an even more aggressive response from the reigning power. In this perilous game of brinkmanship, war is more likely than not.

Yet, the explanation that I have just proposed is founded on the assumption of imperfect information. The fear that might exist between reigning and rising powers is mostly a result of the two countries having to guess each other’s intentions. In today’s information revolution context, will advancements in information technology reduce this fear of the unknown? Maybe.

However, technology alone cannot guarantee effective communication. The key to that is empathy. It is an attitude of respect toward the other party and is expressed in the form of active listening. To avoid the deadly implication of war suggested by Allison’s Thucydides trap narrative, both the U.S. and China need to seriously examine each other’s worldview.

Section II: Conceptual Narrative 2 — The "Tianxia" System

Facing a contemporary world full of conflict, hostility and continuing clashes between civilizations, some Chinese thinkers have looked for nuggets of wisdom from ancient China to illuminate a way out of the Hobbesian context of growing chaos and anarchy. Among these thinkers, Zhao Tingyang is the most influential in bringing a distinctive Chinese concept to Western audiences. He roughly translates “天 下” (tianxia) to “all under heaven” existing harmoniously.

Zhao argues first that tianxia is a rational worldview. To make his point, he introduces an hypothetical: Each player is motivated only to maximize his or her own self-interest within a Hobbesian state of nature, and each player learns and imitates the successful strategies deployed by the others. In the long run, the players are incentivized to consider a strategy of hospitality. This strategic shift toward coexistence is rational because it continues to produce positive payoffs when copied by other players. It is the only strategy that doesn’t provoke retaliation by other players and hence it can successfully withstand the challenge of others imitating it. Given that tianxia is a worldview involving mutual hospitality, it is rational according to Zhao’s hypothetical.

Having established the rational justification for tianxia, Zhao defines the tianxia system as such:

“First, tianxia means the earth under the sky — ‘all under heaven.’ Second, it refers to the general will of all peoples in the world, entailing universal agreement. It involves the heart more than the mind, because the heart has feelings. And third, tianxia is a universal system that is responsible for world order. The world cannot achieve tianxia unless the physical, psychological and political realms all coincide.”

Zhao’s definition of tianxia looks extremely complex. However, it is precisely this complexity that makes it an interesting conceptual narrative to overcome our contemporary world’s complex problems. Though the alignment of the physical, psychological and political realms appears more like an idealistic concept rather than a practical goal, understanding this perspective of harmony can at least help us broaden the conceptual space in which we evaluate different alternatives.

A key aspect of the tianxia system is its mechanism of “化,” or transformation. In his first book, Zhao explains:

“天下理论是一种‘化敌为友’理论,它主张的‘化’是要吸引人而非征服人,所谓‘礼不往教’原则。”

This is how I would translate his sentence: Tianxia theory “transforms one’s enemy into one’s friend,: It advocates transformation and thus works by winning the other person’s heart instead of conquering by force. This is the same principle as “those with rites would attract others to come and learn, instead of reaching outward to educate others.”

Tianxia’s key mechanism of transformation clearly sets it apart from Western worldviews. In fact, Qian Mu, another contemporary Chinese thinker, pointed out that the Chinese and Roman Empires expanded in starkly different ways.

The Roman Empire used its military power as a foundation to expand outward. By contrast, the Chinese Empire used its culture as a focal point and drew the surrounding people inward. This example offers a sharp distinction between the colonial worldview of military expansion and the tianxia system of transformational harmony.

During his speech to world leaders at the Belt and Road Forum in April last year, Xi said the BRI would benefit “all of its participants” — not China only. He said the Belt and Road Initiative is “not an exclusive club,” noting the project would not only serve the interests of China but also enhance multilateralism. According to Xi, the initiative aims to enhance the connectivity and practical cooperation [of the participating countries]… delivering a win-win outcome and common development.” Xi also said that “China would uphold the principles of extensive consultation, joint contributions and shared benefits, maintaining close communication and coordination with all parties to work together with openness, inclusiveness and transparency.”

Evidently, Xi’s latest vision for the development of the BRI is in line with the ideals of the tianxia system.

Section III: Comparing Conceptual Narratives on the BRI

How should we make sense of the competing conceptual narratives regarding the BRI? I propose a comparative framework called the “realist-idealist spectrum.” In this framework, different conceptual narratives are sorted according to their tendency toward either realism or idealism. By “realist” and “idealist” I refer to Roshwald’s definition:

“The perfect realist would only examine the concrete situation objectively, and refrain from any value attitude toward it. The idealist, on the other hand, would keep his ideal in mind also while forming an attitude toward a concrete political situation.”

Under the framework of that realist-idealist spectrum, the Thucydides trap narrative sits at the realist end, while the tianxia system narrative heavily leans towards the idealist end. Clearly, Allison proposes a realist’s interpretation of international politics because he has thoroughly examined similar historical precedents in specific situations of great power competition.

On the other hand, Zhao proposes an idealist interpretation because he has in mind an alternative vision of global harmony inspired by wisdom from ancient China. (Here, I must clarify that the Thucydides trap narrative is not exclusively realist and that the tianxia system is not exclusively idealist.)

While the historical precedents are mostly discouraging, Allison hopes that policymakers can overcome this wave of pessimism by learning key lessons from the few successful cases in which the reigning power and the rising power have avoided direct conflict. Similarly, a group of contemporary Chinese thinkers conducted extensive research on the concrete political climate of ancient China in which the tianxia system was adopted. They have presented a Chinese alternative because they sincerely believe that it offers a valuable conceptual resource for future global leaders to reimagine solutions together.

Within the conceptual framework of “realist-idealist spectrum”, how should we form our own narrative on China’s BRI? In this situation, it appears tempting for us to opt for a compromise solution and take a position somewhere in the middle. However, I shall resist committing this fallacy of the middle ground because taking the middle ground does not necessarily imply that we have reached the best possible solution. Without the support of rigorous research and reasoning, the middle ground is merely a false option. Instead, I propose that we should form a narrative based on the pragmatic considerations of both short-term geopolitical climate and long-term developments in global governance.

Reflection on our choice of conceptual narrative is useful because it allows us to interpret arguments related to the implementation of the BRI under a structured framework. By doing this, we can arrive at a crucial insight: Our reliance on opposing narratives will lead us to very different interpretations of the same event. In this light, the realist-idealist spectrum is especially useful because it serves as a medium for more effective communication between parties holding competing biases. The advantage of elevating to a conceptual level is that in this abstract realm we can reach a higher vantage point from which we can examine our biases and evaluate alternatives to our own narratives.

Section IV: Conclusion

Much scholarly work has focused on interpreting the policy intentions of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. However, I have yet to find an academic article that scrutinizes the underlying assumptions and biases carried by the dominant narratives. This is why I hope that my paper can serve as a starting point for a new type of research on international relations. By applying the ancient Chinese concept of tianxia to the BRI, I am not providing a fixed lens through which all of us should see China’s foreign policies. I am merely offering an alternative narrative that challenges the dominant perspective of Allison’s Thucydides trap.

The realist-idealist spectrum aims to elevate competing narratives to a conceptual level because this would allow us to gain a clearer view of the broader landscape of foreign policy debates. Ultimately, my project hopes to increase the conceptual space in which we understand geopolitical issues such as the BRI. I believe this is a worthwhile enterprise because it opens up new possibilities for a future that features global governance.

In “China and Global Governance,” He Yafei observes:

“In a new era where China is increasingly connected with the world, both the historical trajectory and existing conditions necessitate China’s deep and comprehensive engagement in international affairs. China could and should voluntarily participate in and lead global governance reform. This requires us to fully understand the Western discourse and rationale concerning global governance, including its definition, evolution and corresponding system designs, so that we can apply China’s thinking and Chinese solutions to the needs of global governance.”

Clearly, China offers a rich trove of ancient wisdom to expand the imagination about global governance in the future. In today’s world, we must include the Chinese perspective in our imagination of a global future. We would be foolish and irresponsible to future generations if we were to limit our own imagination.

After asking what our current world is, we must not forget to ask ourselves what our future world can be. In order to imagine a truly inspiring global governance system, we must be sincere in our attempt to understand our historical and cultural differences , as well as the conceptual narratives built upon those differences. Only after understanding our differences can we begin to see our similarities and converge onto a common path toward peace and plenty.