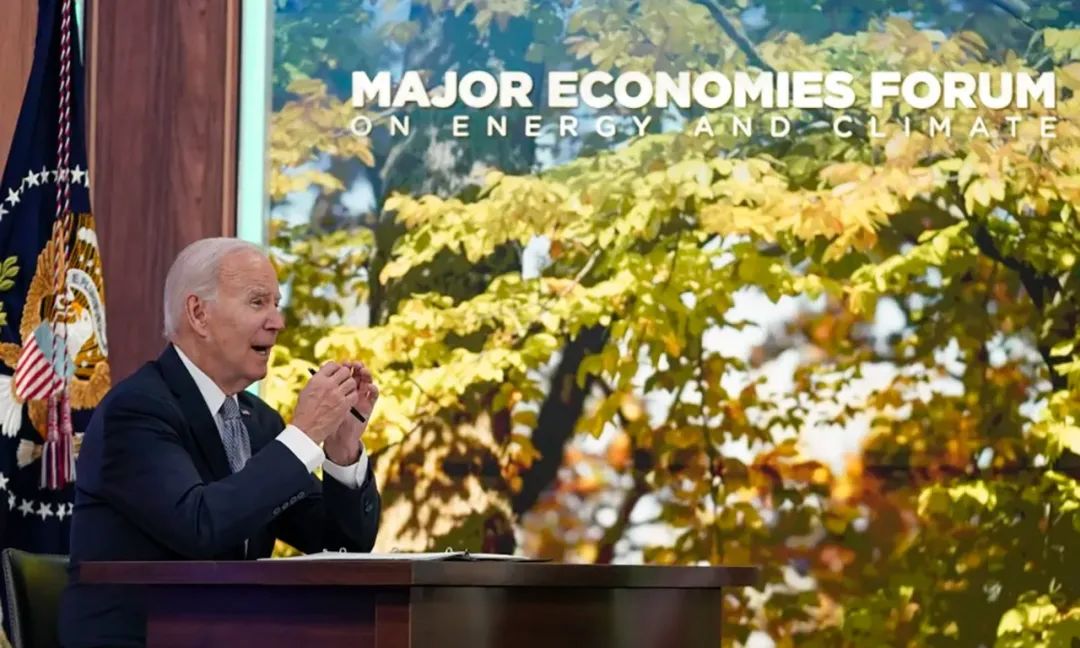

On April 20, U.S. President Joe Biden convened the Major Economies Energy and Climate Forum (MEF) for the fourth time. It is worth noting that after the accession of Italy, the number of member countries of the Net-Zero Government Initiative (NZGI) — which was launched by the United States at COP27 in 2022 — has expanded from 19 in the beginning to 21 today. According to the requirements set by Washington, a country is qualified to join the initiative so long as its national government promises to achieve the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, formulate a road map for net-zero commitments before COP28 and develop medium-term goals and release the road map.

Through the MEF, Washington aims to expand the NZGI’s membership and is expected to create forums and platforms to coordinate and advocate net-zero policies among the participants. Especially at a time when COP28 has become an important milestone in reviewing the worldwide implementation of the Paris agreement, Washington will redouble its efforts to promote the NZGI to build a green alliance around the world. This, however, will pose new challenges to the global climate governance system with the United Nations at the center.

Green alliance weakens UN governance

To establish a rules-based climate governance system, the United States is focused on establishing a “green alliance” through bilateral and multilateral channels, which would launch new platforms, rules and initiatives. Last year, the Biden administration enhanced climate diplomacy under the framework of the Indo-Pacific Strategy. It established the U.S.-Japan Climate Partnership, the Japan-U.S.-Mekong Power Partnership (JUMPP), the U.S.-India Climate and Clean Energy Agenda 2030 Partnership, the Quad Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Package (Q-CHAMP), the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA) in the Indo-Pacific region, and the Blue Pacific Partnership (PBP) in the South Pacific region.

Meanwhile, to institutionalize coordination with its climate partners across the Atlantic, a working group on climate and clean technology was established under the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council to support transatlantic trade and investment in climate-neutral technologies, products and services.

As the two green alliances in the Indo-Pacific and the Atlantic regions complement each other, the strategic goal of the United States in building the NZGI is to establish a wider green alliance based on the 2050 net-zero rule at the government level of major developed countries, thus more effectively bypassing the UN-centered multilateral governance platform to dominate rules and systems on global climate governance.

Net-zero timeframe erodes UN framework

Currently, global climate governance is largely built within the United Nations’ multilateral framework centered on the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris agreement. The cornerstone of this framework is the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, which requires developed countries to assume responsibility for their historical emissions and developing countries to take on international responsibilities in line with their respective national conditions and capabilities.

The Paris agreement forms a bottom-up model of nationally determined contributions, which ensures the fairness and rationality of global climate governance. An important mission of COP28 this year is to review the worldwide implementation of the NDCs as stipulated in the Paris agreement, so as to examine the gap between actions and goals and enhance global climate action capabilities. The emphasis is on encouraging developed countries to honor their capital and technology commitments.

In expanding the NZGI, Washington aims to achieve two goals, step by step. First, it persuades more developed countries to join the initiative to develop net-zero rules. Second, in the name of climate justice it uses international multilateral platforms to force China, India and other large developing countries to boost their emission reductions and shorten their net-zero emission timetables. At present, developed and developing countries have different net-zero emission timetables, as do countries in different stages of development. Therefore, Washington’s effort to expand the NZGI is essentially to force major developing countries to reduce their time for emission reduction, thus weakening the historical responsibility of developed countries.

Competition for green power

While it’s only a small part of the U.S. climate strategy, the NZGI demonstrates that America relies on the green alliance it is building to conduct climate diplomacy in terms of green finance, trade, transportation, clean energy innovation, temperature goals, methane emissions reductions and green infrastructure standards. Ultimately, it wants to promote its governance agenda and rules to the international community and to the United Nations, thereby consolidating its power in green finance, innovation and climate security.

The vast number of developing countries not only live with the impact of climate change but also face the threat of unilateralism and hegemony amid changes in global climate governance. It means that they need to embrace the concept of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security, strengthen multilateral cooperation (with, for example, the Group of 77 and China) and join hands to maintain the authority of the United Nations and its status as the main platform in global security governance.

Additionally, they need to maintain the stability of the global climate governance system based on the UNFCCC and the Paris agreement, protect the rights and security of developing countries in global climate governance and together build a global climate governance system that is equitable and fair — and one that produces win-win results.