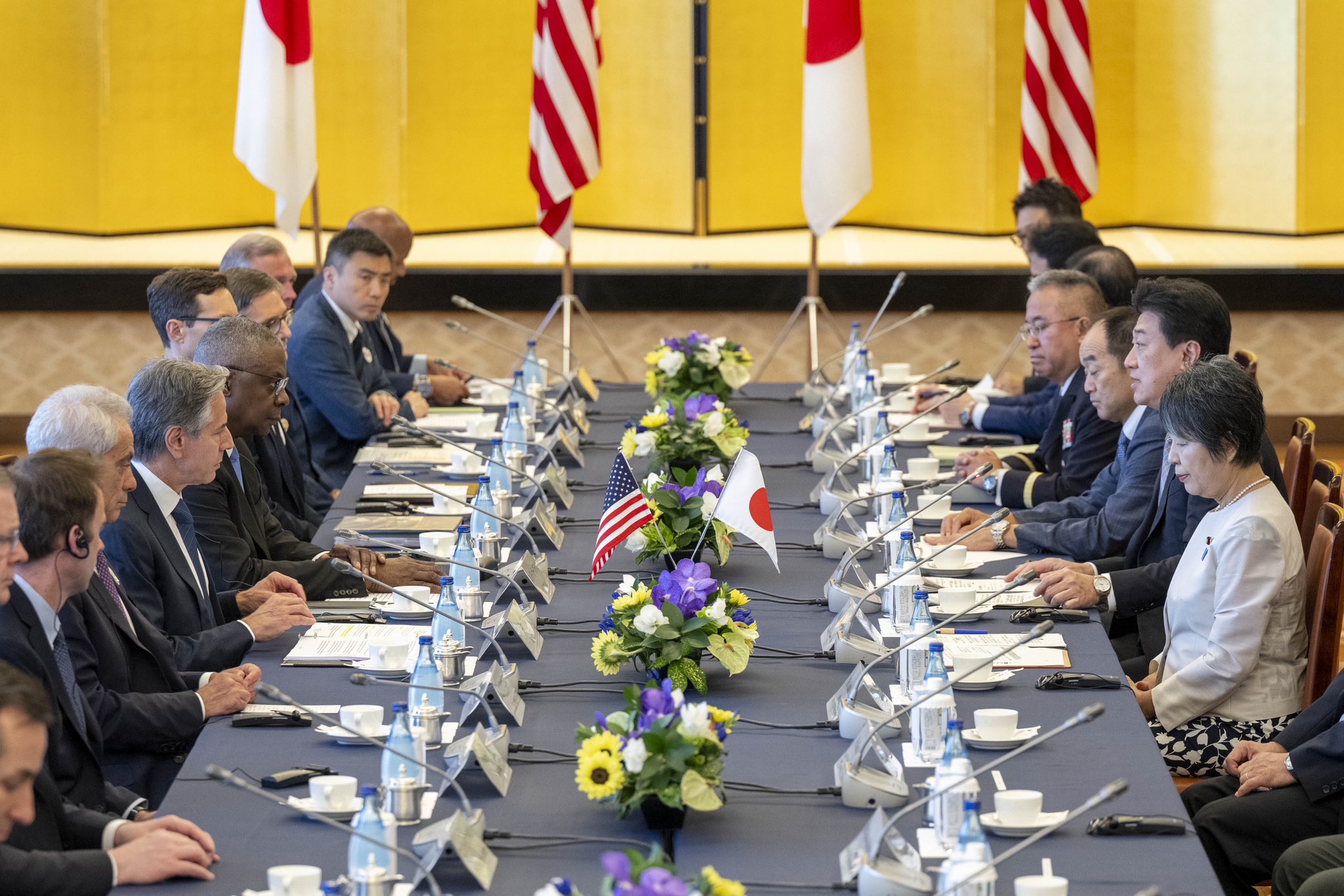

Foreign ministers and defense ministers from the United States and Japan met in Tokyo at the end of July. One of the main highlights of this meeting was the initiation of their first dialogue on extended deterrence.

During the dialogue, the United States reaffirmed its commitment to leveraging its full range of military capabilities, including nuclear weapons, to ensure Japan’s security. And in the joint statement issued after the meeting, the two nations expressed their intention to enhance nuclear deterrence as a means of strengthening the overall deterrence capabilities of their alliance. This signifies the establishment of a ministerial-level mechanism on extended nuclear deterrence between the two — essentially giving the United States a formal rationale for providing Japan with a nuclear umbrella.

In the statement, the two nations also stated that “the People’s Republic of China’s foreign policy seeks to reshape the international order for its own benefit at the expense of others. … Such behavior is a serious concern to the Alliance and the entire international community and represents the greatest strategic challenge in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond.” In other words, it is imperative for the U.S. and Japan to strengthen their nuclear hand in response to what they view as their “greatest strategic challenge” — that is, Beijing.

Why is there such a strong emphasis on nuclear deterrence this time? What does this development mean for China-U.S.-Japan relations and the security landscape in East Asia?

First, it reflects Japan’s concerns about the credibility of United States security commitments. From Japan’s perspective, the balance of power in East Asia is increasingly tilting in favor of China, while U.S. power is declining. If Donald Trump returns to the White House in January, Washington’s security commitments to all its allies could diminish. Officially, the dialogue on extended deterrence was held in response to the accelerated expansion of nuclear forces in North Korea, China and Russia; but at a fundamental level, Japan hopes to enhance the credibility of its alliance with the U.S. by pushing it to make a clear nuclear commitment. At the same time, the United States seeks to maintain the confidence of its East Asian ally by reinforcing its position.

Second, Japan hopes to participate in the U.S. nuclear decision-making process through this mechanism to achieve greater equality and strategic autonomy in the bilateral relationship. Because of escalating tensions in China-U.S. relations and the relative decline of U.S. power, Japan’s role in the Washington’s East Asia deterrence strategy takes on greater significance. A shift provides an opportunity for Japan to reshape, if not reverse, the traditional dominance of the United States in the alliance.

Additionally, under pressure from the Ukraine crisis in Europe and the Gaza conflict in the Middle East, the United States now increasingly relies on Japan to maintain security in East Asia. In its 2022 national security strategy, the Japanese government aimed to increase the defense budget to 2 percent of GDP and give itself the ability to mount effective counterstrikes against opponents. While these goals are interpreted as Japan’s contribution to U.S. deterrence in the region, the dialogue has also been taken as part of Japan’s effort to elevate its status in the alliance.

For Tokyo, however, there have been questions about the reliability of U.S. nuclear protection — after all, it involves the United States using its military might to protect other nations, not itself. As the issue of reliability has now emerged as a priority on the alliance agenda, Japan assesses it by studying developments on two fronts: First, the U.S. has repeatedly reaffirmed its commitment to using its military strength, including nuclear power, to protect Japan. Second, there are military deployments involving nuclear forces.

Apparently, the United States’ strengthening of nuclear protection for Japan is essentially a balancing act between the two countries, but it incorrectly imagines that China is an enemy. This unilateral move, without any diplomatic communication, threatens to perpetuate negative perceptions across the region and could ultimately lead to a greater sense of insecurity among these countries.

Lasting peace in East Asia cannot be achieved simply by strengthening nuclear deterrence. The way forward is to focus on common security efforts rather than excluding key parties from regional security discussions.